|

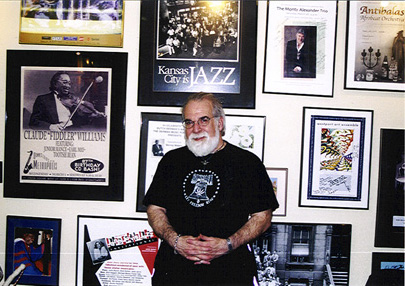

Butch Berman

Berman Memorial

NJO Russ Long Tribute

Tomfoolery

Memorial for Earl May

|

|

March 2008

Feature Articles

Music news, interviews, opinion, memorials

|

|

|

BMF to keep Butch's

memory alive

By Tom Ineck

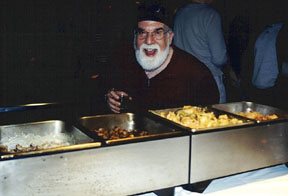

LINCOLN, Neb.—The Berman Music

Foundation lost its guiding light and

most passionate supporter when Butch

Berman died Jan. 31.

More

than simply the founder of the BMF,

Butch was a veteran rocker and a friend

to musicians and non-musicians alike. A

master of networking, Butch touched so

many lives in so many ways during his

brief 58 years that it is impossible to

document his impact in one story.

In an

attempt to do him justice, we at the

Berman Music Foundation will keep

Butch’s memory alive by continuing to do

interviews with the rock musicians with

whom he played, the jazz artists who

experienced his generosity and

friendship and others whom he met and

developed friendships with in every

aspect of his life.

Bill

Dye,

a guitarist now living in

Kansas City,

Mo., is a former bandmate of Butch’s in

The Megatones, a raucous rockabilly and

rhythm ‘n’ blues band that ruled Lincoln

from 1973 to 1976, once opening for

bluesman Freddie King and frequently

holding court in the early days of the

Zoo Bar. Kansas City,

Mo., is a former bandmate of Butch’s in

The Megatones, a raucous rockabilly and

rhythm ‘n’ blues band that ruled Lincoln

from 1973 to 1976, once opening for

bluesman Freddie King and frequently

holding court in the early days of the

Zoo Bar.

Dye

fondly remembers Butch’s unique outlook

on life.

“When

you entered Butchworld, he had this

weird little, rarified environment. On

one hand, he was able to do everything

on his own terms. I’m a spoiled, only

child, too, so we had that in common,”

Dye said. “The thing about Butch was

that even though he saw the world

through his own rose-colored glasses, he

was always very generous and outgoing

and friendly towards other people. He

wasn’t a selfish man, at all. He was

self-involved, but he was not selfish.”

The two

met in the early ‘70s, when Berman was a

member of a band called The

Kaleidoscope. Because Butch had

inherited his family’s wealth, “he lived

in this little world, like, ‘I am the

emperor of my domain and nothing

challenges me.’ He hardly ever had to do

a job in his life,” yet he kept busy

collecting records and playing music,

even when bandmates proved difficult to

work with, Dye said. “One of the things

that impressed me about Butch is that he

didn’t like being angry or mad at

people. He wanted to find a way to get

away from it.”

Butch

had a 1975 cassette tape recording of

The Megatones performing at Little Bo’s,

a notorious Cornhusker Highway club in

Lincoln. In recent years, he dubbed it

to CD and gave Dye a copy.

“I’ve

put it on a couple times and thought,

‘Wow, this isn’t just nostalgia. We were

ass-kickin’.’ The sound quality is just

OK, but we sound like the MC5.” The two

also shared the bandstand in The

Excessives from 1980 to 1981, a rock ‘n’

roll experience Dye remembers fondly.

“That

was pretty much his band, he was leading

the group, and he was always an utterly

reasonable, pleasure to work with,” he

said. “He was always very organized,

knew what was going on. And, he was

always a very fair-minded guy. He wanted

to be a fair-minded person, as a

bandleader and just as a person.”

Another

thing they had in common was collecting

records.

“Over

the years, we were always trying to turn

each other on to things,” Dye said. A

visit to Butch’s house would eventually

turn to a listening session that

involved an exchange of obscure 45s.

“Sometimes I would bring stuff over for

him, and he would be interested in that.

He was open to other people bringing

stuff to him, as well. He was more of a

hardcore collector than I was. I used to

be more of a collector than I am now,

but Butch never let up.”

Most

memorable for Dye was Butch’s

thoughtfulness.

“Over

the years, I can’t tell you how many

times he would remember my birthday or

give me some little gift and say, ‘I

found this 45 and thought of you. Here.’

It was not just with me. He was one of

the most thoughtful people I’ve ever

known.”

Dye also

remembers Butch as a friendly

conversationalist, even with people he

hardly knew. After moving to Kansas City, he would occasionally return to

visit family and friends.

“One of

those times I was in town, my mom said,

‘Oh, I ran into Butch Berman the other

day at the grocery store. I could barely

get away from him. He wanted to talk and

talk and talk about all kinds of things.

What a nice fella, but boy he can talk!’

She got a kick out of Butch.”

Karrin Allyson’s association with Berman Music Foundation is the longest

one on record,

beginning with a March 1995 booking at

the Zoo Bar in Lincoln. The foundation

brought her back to the Capital City

numerous times to play the Zoo Bar, a

now-defunct club called Huey’s and

eventually a concert performance in

November 2001 at the Lied Center for

Performing Arts, where Allyson was

accompanied by a Kansas City rhythm

section and string players from the

Lincoln Symphony Orchestra. one on record,

beginning with a March 1995 booking at

the Zoo Bar in Lincoln. The foundation

brought her back to the Capital City

numerous times to play the Zoo Bar, a

now-defunct club called Huey’s and

eventually a concert performance in

November 2001 at the Lied Center for

Performing Arts, where Allyson was

accompanied by a Kansas City rhythm

section and string players from the

Lincoln Symphony Orchestra.

Berman

had first heard Allyson in Kansas City,

where she often performed at The Phoenix

Bar & Grill and at Jardine’s. He soon

found new venues for her to practice her

craft.

“He was

so avid about giving artists venues and

avenues to play,” Allyson said. “I was

in the club scene, the bar scene, every

day of my life, and he offered me one of

the first opportunities to actually play

for a real listening audience, like a

concert setting. It gives you a

different way to explore your art. He

was always interested in doing different

things. He was a very creative person,

and he was excited about stuff. He

always wanted to do more of something.

It was never less of something.”

Allyson

also met up with Berman when the

foundation covered the Topeka Jazz

Festival from the late 1990s until 2005.

After-hours parties in the hotel were

not uncommon, and Butch loved to be

there.

“He

always wanted to hang out,” Allyson

said. “I’m always on the road, so I’m

always trying to conserve energy a

little bit. I like to hang out too, but

I felt bad that I didn’t do it as

often as I would have liked to with

Butch. But we had our share.”

Russ

Dantzler

and Berman were still in there teens

when they met in 1968. A

resident of New

York City for many years, Dantzler

operates Hot Jazz Management and

Production and has worked with jazz

artists Claude “Fiddler” Williams, Benny

Waters, Earl May and many others. resident of New

York City for many years, Dantzler

operates Hot Jazz Management and

Production and has worked with jazz

artists Claude “Fiddler” Williams, Benny

Waters, Earl May and many others.

When he

graduated from high school, Dantzler

moved into a house in Lincoln with three

roommates, all women. One of them was

dating Berman, who would pick her up

there. The two got to know each other

better.

“He had

a passion for turning people onto

things, whatever they were,” Dantzler

said. “He also had a passion for

discovering new things. I don’t know

which was greater, sharing it or finding

it himself. That was one of the neatest

things about him, and that rang true

practically every time I saw him. He had

some new band or some thing new

that he had to share.”

Like

many others who frequented the Zoo Bar

and other rock venues in the mid-‘70s,

Dantzler loved The Megatones and

Berman’s rockabilly piano playing.

“That

was the only band in Lincoln that made

me want to dance just about every time I

heard them. And, I’m not a good dancer.

I loved Butch’s keyboards. I loved his

guitar playing, but I really loved his

keyboard work.”

Because

of Dantzler’s long residence in New York

City and his contacts with jazz

musicians, Butch often called on him for

long-distance help in making

arrangements or helping with publicity.

At times, Dantzler found himself at the

mercy of Butch’s jazz obsessions and

incapable of delivering exactly what

Butch wanted. In the weeks before

Berman’s death, they talked about

organizing a benefit concert for Norman

Hedman, leader of the Latin jazz group

Tropique and a longtime friend and

consultant of the Berman Music

Foundation. Hedman also is having health

problems related to cancer.

Dantzler

said his final phone conversation with

Berman illustrated Butch’s generosity

and thoughtfulness.

“I’m

still kind of knocked out by the last

conversation, where it was all about

helping someone else. He actually called

me twice one week before he died, and it

was about helping Norman, of course.”

It was

Dantzler who introduced Butch to singer

Kendra Shank in New York City in

1995.

“I was

building a following in New York at that

time,” Shank recalled. “Russ was finding

every way possible for me to sit in with

musicians and meet musicians and expand

my presence on the New York jazz scene.

Butch heard me sing, and I guess he

really liked what he heard.” “I was

building a following in New York at that

time,” Shank recalled. “Russ was finding

every way possible for me to sit in with

musicians and meet musicians and expand

my presence on the New York jazz scene.

Butch heard me sing, and I guess he

really liked what he heard.”

A few

months later, Berman booked Shank as

part of a New York All-Stars performance

in August 1995 at the Zoo Bar in

Lincoln, with a side trip to Kansas City

for another gig. The all-star band

included Jaki Byard on piano, Jimmy

Knepper on trombone, Claude “Fiddler”

Williams on violin, Earl May on bass and

Jackie Williams on drums.

“A whole

lot of things came together out of that

one trip. It was sort of a blossoming of

a whole bunch of events that really

propelled my career forward,” Shank

said. “I just remember being so honored

to be included because that was pretty

early in my jazz career. To be included

in something that was being called an

‘all-star’ event was very flattering and

humbling.”

When

Butch was in NYC, the two would get

together for dinner, to check out a jazz

club or just have “long, long talks

about everything under the sun—life,

relationships, music. I always

appreciated his passion. It just seemed

he lived his life every second. He never

passed up a moment to enjoy his life.”

Shank

was especially impressed with his

burning desire to use his philanthropy

to make good things happen.

“I feel

really blessed to have been one of the

people that he chose to support. It’s

meant so much to me. You know how hard

it is for artists. You know what this

life is like. You have no financial

security, no job security. You’re doing

this thing that means the world to you,

that’s a spiritual path as much as

anything. You put yourself out there,

not knowing whether anyone is going to

give a damn. When someone like that

supports you by producing me in concert

a few times, that’s supporting my art.”

Shank

also witnessed and understood Berman’s

zeal to introduce audiences to

unfamiliar artists.

“One of

the things I really admired about Butch

is the way he seemed to have a vision

and a sense of a mission and how he

would bring artists to Lincoln who might

not otherwise have been presented there,

who might not have been in tune or in

keeping with the general tastes of the

audiences there,” she said. “He didn’t

waver when he had a belief in

something. I felt he was a person of

great integrity. Maybe he was just

stubborn. He was a jazz evangelist.”

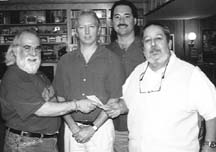

Gerald Spaits,

a Kansas City bassist and

BMF

consultant, met Berman at the

Topeka

Jazz Festival in the late 1990s. After

the Russ Long Trio CD “Never Let Me Go”

had been recorded in 2001, Spaits turned

to Berman as one of several possible

backers who would help to bankroll the

release. Instead, he put up all the

money necessary to issue the release. Topeka

Jazz Festival in the late 1990s. After

the Russ Long Trio CD “Never Let Me Go”

had been recorded in 2001, Spaits turned

to Berman as one of several possible

backers who would help to bankroll the

release. Instead, he put up all the

money necessary to issue the release.

The trio

visited Lincoln and got better

acquainted with Butch, always a

requirement for his love of networking

and camaraderie. The BMF later booked

the trio—and other bands that utilized

Spaits’ bass prowess—at P.O. Pears in

Lincoln. Other gigs followed at Jazz in

June and in planning the 2005 Topeka

Jazz Festival, for which Berman served

as music director. Eventually, Spaits

and his wife, Leslie, became BMF

consultants.

“He was

a unique individual,” Spaits said. “He

put it all out there. He didn’t mince

any words. If he didn’t like something,

he’d let you know. It’s like he would

have to clear the air once in a while.

That was just Butch.”

Dave

Fowler

first heard of Berman many years ago,

when he read a music

magazine article

that singled out a Lincoln guitar player

for his “letter-perfect vocabulary of

Scotty Moore,” the legendary guitarist

best known for backing Elvis Presley in

the early part of his career. magazine article

that singled out a Lincoln guitar player

for his “letter-perfect vocabulary of

Scotty Moore,” the legendary guitarist

best known for backing Elvis Presley in

the early part of his career.

“That

was my introduction to Butch. He was an

expert in that straight-ahead,

rockabilly guitar style.”

Fowler,

a violinist, and Butch struck up a

friendship over the years and eventually

were occasional bandmates in an early

version of Charlie Burton’s band, the

Dorothy Lynch Mob. But Fowler also took

an interest in the Berman Music

Foundation’s collection of rare music

videos by such artists as Claude

“Fiddler” Williams and a group of jazz

all-stars who the foundation brought to

Lincoln’s Zoo Bar in the mid 1990s.

“The

resources that he put together in that

museum are just incredible,” Fowler

said. “It ranges from obscure Homer and

Jethro 45s to the very first time that

(jazz pianist) Eldar Djangirov played in

Lincoln. He covered so many different

areas of jazz.”

One of

the things that Fowler and Butch had in

common was a love of “gypsy jazz,” that

hybrid swing style made popular by

guitarist Django Reinhardt and violinist

Stephane Grappelli, founding members of

the Hot Club of Paris quintet in the

1930s.

“Right

up until the last weeks that I saw him,

we were still planning some musical

ideas that he wanted to carry out. He

had brought the Hot Club of San

Francisco back. He was thinking of doing

that again and having some local people

play as part of a gypsy jazz festival.

“I find

it very hard to think that he’s not

around.”

top |

|

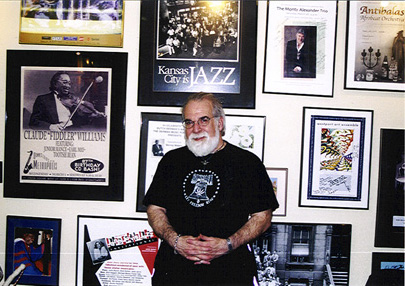

Memorial

BMF founder Butch Berman, 58, died Jan.

31 |

|

Dear readers: In case you

missed the news stories on the passing

of Butch Berman, or wish to know more

details of his life, we offer the piece

below, which appeared in a slightly

different form in the Feb. 1 Lincoln

Journal Star.

By Tom Ineck

LINCOLN,

Neb.—Byron L. “Butch” Berman, 58,

founder of the Berman Music Foundation

and veteran of many Lincoln rock bands,

died at home the evening of Jan. 31,

after a four-month struggle with brain

cancer.

Since

its inception in spring 1995, the BMF

has sponsored dozens of jazz concerts

throughout the Midwest, including

appearances in Lincoln by pianists

George Cables, Eldar Djangirov, Kenny

Barron, Monty Alexander, and Joe

Cartwright; Norman Hedman’s Tropique;

the Hot Club of San Francisco; singers

Karrin Allyson, Kendra Shank, Giacomo

Gates, Sheila Jordan, and Kevin

Mahogany; saxophonists: Bobby Watson,

Joe Lovano, and Greg Abate; trumpeter

Claudio Roditi; guitarist Jerry Hahn;

bassist Christian McBride; the Mingus

Big Band and many others.

The

foundation and the Nebraska Jazz

Orchestra are collaborating on a May 23

tribute to the music of the late Kansas

City pianist and composer Russ Long.

Over the years, the foundation has

sponsored many groups for the Jazz in

June concerts in Lincoln, and right up

to Butch’s death he was working on a

lineup for this year’s series. We will

share details as they become available.

Berman’s

varied interests in music, however, go

back a lot farther than the jazz

foundation. At age seven, he was taking

lessons in classical piano. An only

child raised in 1950s Lincoln, the

precocious audiophile had collected 300

rock ‘n’ roll 45s by age 10. He also had

begun playing guitar and improvising on

the keyboard.

Berman

played in a succession of local rock

bands in the early 1960s, including the

Modds, who were inducted into the

Nebraska Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame. He

grew his hair long and considered

dropping out of school. At age 15, he

was sent to Wentworth Military Academy,

where, instead of discipline, the young

cadet was introduced to all the thrills

and excitement of Kansas City, just 40

miles down the road.

By the

early 1970s, Berman was back on the rock

scene in Lincoln, playing guitar and

keyboards in a number of bands,

including such regional favorites as The

Megatones and Charlie Burton & Rock

Therapy. He even toured Europe with

rockabilly legend Sleepy LaBeef. The

1980s found him in San Francisco,

hanging out at Jack’s Record Cellar,

playing with Roy Loney & the Phantom

Movers and beginning to acquire an

interest in jazz.

Returning to Lincoln in the early 1990s,

he continued to build a large and

diverse record collection and began an

eight-year stint as a jazz deejay,

hosting “Bop Street Theater,” “Reboppin’,”

“Reboppin’ Revisited” and “Soul Stew” on

KZUM Community Radio. He also maintained

his rock music career, most recently

with the Cronin Brothers, with whom he

performed his last gig Dec. 30 at the

Zoo Bar.

In May

2003, Berman married his soul mate,

Grace, whom he often referred to as his

“saving Grace” and “loving angel.”

Together, they traveled to New York

City, Chicago, San Francisco, Kansas

City, Mo., and elsewhere and especially

enjoyed going to concerts and dining

with friends. Butch enjoyed interacting

with Grace’s sons, Jenom and Bahji. He

also had a lifelong love and respect for

animals, wild and domestic, and adopted

many dogs and cats over the years, most

recently cat Muggles and dog Peanut.

top |

|

Concert Preview

Berman inspired May 23 Russ Long tribute

with NJO |

|

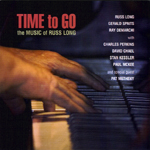

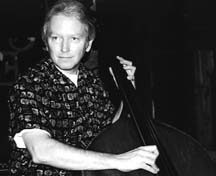

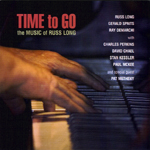

By Tom Ineck

It was Butch Berman who conceptualized

the May 23 concert that will pair the

Nebraska Jazz Orchestra and a coterie of

Kansas City musicians for a tribute to

the music of late KC pianist and

composer Russ Long.

Through the auspices of the Berman

Music Foundation, he funded the 2006

project to document Long’s compositions

with new arrangements for septet and a

recording entitled “Time to Go: The

Music of Russ Long.” Long died Dec. 31,

2006, just weeks after the CD’s release.

The recording had been selling well in

the Kansas City area, but Berman wanted

to introduce the music to a Lincoln

audience. He approached the Nebraska

Jazz Orchestra, with whom the BMF had

collaborated in bringing many guest

artists, including saxophonists Bobby

Watson and Greg Abate, trumpeter Claudio

Roditi and singer Giacomo Gates. The recording had been selling well in

the Kansas City area, but Berman wanted

to introduce the music to a Lincoln

audience. He approached the Nebraska

Jazz Orchestra, with whom the BMF had

collaborated in bringing many guest

artists, including saxophonists Bobby

Watson and Greg Abate, trumpeter Claudio

Roditi and singer Giacomo Gates.

“Butch had just finished this CD project

with Russ, and he was all excited about

that,” said Ed Love, NJO music director.

“He said he would be very excited to

fund a concert Russ Long’s music and all

new arrangements and even bring up a

rhythm section from Kansas City.”

Love chose three tunes with interesting

chord changes that NJO musicians would

enjoy playing and listeners would enjoy

hearing. Bandmates Mark Benson, Dave

Sharp and Peter Bouffard will arrange

“Time to Go,” “Meatloaf” (based on the

changes of “I Got Rhythm”) and “I Don’t

Care Who.”

Berman also broached the subject with

Gerald Spaits, Kansas City bassist and a

BMF consultant. It was Spaits who had

spearheaded the “Time to Go”

arrangements and recording.

“It was really Butch’s idea,” Spaits

said of the plan to involve the NJO. “He

asked me if we could do some of those

arrangements for a big band and do it

with NJO. I thought that would be a

great idea. It kind of came out of the

blue, because it’s not something that I

would have thought of, although I think

it’s appropriate, and it’s something

that Russ would have really liked.”

Spaits also will arrange three tunes for

the NJO concert, “Parallel,” “Woodland

Park” and “Can City.”

“We’ll see what happens,” he said with

some trepidation. “It’s going to be

really interesting to see because I have

no idea what they’re going to do with

the three tunes. I picked three that I

thought would make good arrangements. I

didn’t want to do all six of them, just

because that’s a lot of work. It’s a

long process for me. I’ve done big-band

arrangements, but I haven’t done one for

10 or 15 years.”

Kansas City will be well represented at

the May 23 performance. Accompanying

Spaits for the trip are pianist Roger

Wilder, drummer Ray DeMarchi and reed

virtuoso Charles Perkins.

“I’m excited to work with those

rhythm-section guys from Kansas City,”

Love said. “They’re just amazing

musicians. It will be quite fun.” In

addition to their work with the NJO, the

KC musicians will perform a short set of

Long’s tunes as a quartet.

Butch was a

big fan of Long's, funding the

release of 2001’s “Never Let Me Go,” a

trio recording with bassist

Spaits and drummer DeMarchi. He was

attracted by Long’s sense of ironic wit,

his bluesy vocalizing, his modesty and,

of course, his diverse talents as

composer, song interpreter, pianist and

singer. An important link in KC jazz

history, Long had known or worked with

some of the region’s greats, including

Eddy “Cleanhead” Vinson, Claude

“Fiddler” Williams, Jay McShann and

Frank Smith. Butch was a

big fan of Long's, funding the

release of 2001’s “Never Let Me Go,” a

trio recording with bassist

Spaits and drummer DeMarchi. He was

attracted by Long’s sense of ironic wit,

his bluesy vocalizing, his modesty and,

of course, his diverse talents as

composer, song interpreter, pianist and

singer. An important link in KC jazz

history, Long had known or worked with

some of the region’s greats, including

Eddy “Cleanhead” Vinson, Claude

“Fiddler” Williams, Jay McShann and

Frank Smith.

A longtime friend and bandmate of

Long’s, Spaits sees the Lincoln concert

as a way to educate more people about

the composer’s music.

“I think it’s significant because it is

someone who didn’t get his due,” Spaits

said. “We’re celebrating Russ’s talent.

He made three recordings, and this last

one we got in just before he passed. It

documents the fact that he was a major

talent, in my opinion. I also think he

was a major contributor to Kansas City

jazz.”

Both Russ Long CDs are nearly sold out

and may be reissued with help from the

BMF, a subject of conversation just

weeks before Butch’s death.

Editor's Note: To read more

about Russ Long and his music in an

interview the BMF did with him shortly

before his death

click here. To read about the CD

release party for "Time to Go"

click here.

For a CD review

click here.

top |

|

Tomfoolery

Berman workplace was also a jazz

playground |

|

By Tom Ineck

LINCOLN, Neb.—Work and play were all the

same to Butch Berman, who in the spring

of 1995 formed the Berman Music

Foundation to “protect and promote

unique forms of jazz music” during his

lifetime and beyond. With that mission

statement as its legal underpinning, the

foundation became not only Butch’s

workplace, but his playground—a jazz

sandbox where he could build majestic

castles or just romp with his friends.

Since

my association with the foundation began

as a writer in early 1996, Butch allowed

me to do what I enjoy most, listening to

and writing about jazz. Since the

mid-1980s, I had been doing that for the

Lincoln Journal Star newspaper—at least,

as often as I could justify it to my

editors. Butch let me indulge my passion

for jazz to the extreme, a passion he

shared. Since

my association with the foundation began

as a writer in early 1996, Butch allowed

me to do what I enjoy most, listening to

and writing about jazz. Since the

mid-1980s, I had been doing that for the

Lincoln Journal Star newspaper—at least,

as often as I could justify it to my

editors. Butch let me indulge my passion

for jazz to the extreme, a passion he

shared.

Since

then, I have assumed the additional

roles of editor and webmaster for the

BMF. In the last five years, since the

periodical newsletter went to a

completely digital publication, I worked

especially closely with Butch, and I

will miss our collaborations. To cover

the latest in regional jazz, much of

which was being presented by the Berman

Music Foundation, we traveled to

festivals in Kansas City, Mo., and

Topeka, Kan., and met at local venues

like the Lied Center for Performing

Arts, the Cornhusker Hotel, the Embassy

Suites, Westbrook Recital Hall, the Zoo

Bar, the outdoor Jazz in June concert

series, the Royal Grove, the Downtown

Senior Center and the now-defunct P.O.

Pears, Café de Mai, Huey’s, Ebenezer’s

and Prime Time.

One of

the most enjoyable musical adventures

was a road trip last summer to the

Brownville Concert Hall to hear singer

Klea Blackhurst with pianist Billy

Stritch, bassist Gerald Spaits and

drummer Ray DeMarchi. My wife, Mary

Jane, and I joined Butch and his wife,

Grace, for a pleasant Sunday afternoon

of good conversation and good music.

Working

with Butch could be thrilling,

educational, intoxicating,

unpredictable, exasperating, even

maddening. When I began editing all

stories and he had gotten his first home

(laptop) computer, he would invite me

over to his basement office to take

dictation. He would scribble his stories

on paper beforehand, then attempt to

read them back to me as I typed

furiously on his unfamiliar keyboard,

while his latest musical find was

blaring on the stereo, the dogs were

trying to lick my face, and the

complementary wine and other party

favors were beginning to go to my head.

With Butch, work and play were always

interchangeable.

Eventually, he learned how to write his

stories on the computer and e-mail them

to me for editing. It cut down on the

work time, but it wasn’t nearly as

memorable—or as much fun.

Like

many who grew up in Lincoln, I became

aware of Butch Berman as a musician,

first seeing him perform at the Zoo Bar

in 1974 with The Megatones, one of the

great Midwest rock ‘n’ roll bands of

that era. He was a manic piano player,

perfectly suited to The Megatones’

raucous rockabilly antics, which were

inspired and led by the frenzied

singer-songwriter Charlie Burton.

Butch

continued his rock ‘n’ roll career, and

I would again hear him with Charlie

Burton & Rock Therapy, Pinky Black and

the Excessives, The Tablerockers and, in

more recent years, Charlie Burton and

the Dorothy Lynch Mob and The Cronin

Brothers, his final band.

When

Butch launched the foundation in 1995,

he called me at the Journal Star to ask

me to write a story about it. We met for

an interview and I wrote the story, the

first local coverage for the BMF. In

retrospect, it seems inevitable that we

would work together—and play together. When

Butch launched the foundation in 1995,

he called me at the Journal Star to ask

me to write a story about it. We met for

an interview and I wrote the story, the

first local coverage for the BMF. In

retrospect, it seems inevitable that we

would work together—and play together.

Butch

and I shared the astrological water sign

of Pisces, and it formed a bond that was

significant for both of us. He may not

have considered himself a guru, but I

do. To everyone he met and everyone he

worked with, he taught the simple

lesson: Enjoy life!

I hope

to have many more memorable experiences

with the Berman Music Foundation, and

Butch’s spirit will be present in

everything we do. May the music never

end.

For a glimpse into the future of the

Berman Music Foundation, read Tony

Rager’s column here.

top |

|

Memorial

We just lost one of the best – R.I.P., Earl May |

|

Editor's Note: This was the last

story that Butch Berman wrote. Like so

many other things about Butch, it

illustrates his thoughtfulness, even in

the final stages of his own terminal

illness.

By Butch Berman

![Earl May [Courtesy Photo]](media/308earlmay.jpg) After

losing the wonderful and talented likes

of the late great Frank Morgan and then

Oscar Peterson at the end of 2007, I had

high hopes that 2008 would bring more

joy than sorrow. After

losing the wonderful and talented likes

of the late great Frank Morgan and then

Oscar Peterson at the end of 2007, I had

high hopes that 2008 would bring more

joy than sorrow.

Alas,

one of the dearest, oldest friends and

greatest gentlemen I’ve dealt with since

I’ve been involved with the fabulous

world of jazz the past 20-plus years

passed away Jan. 4 from a heart attack

at the age of 80. I’m talking about the

legendary, left-handed Earl May, one of

the best bassists in jazz history.

I met

Earl through my old Lincoln buddy Russ

Dantzler, whose Hot Jazz Management

moved Russ to NYC many years ago. He

lined me up to do my first interview on

my original KZUM “Reboppin’” radio show

during the early ‘80. I treasure those

cassette phone interviews transferred to

CDs and hope to make them available to

the public sometime in the near future.

Earl

told of his early start in music as a

youngster listening to old jazz records

at his aunt’s in New York before moving

to the Sugar Hill section of Harlem and

finally making music his career.

Starting on the violin, and later

wanting to be a drummer, he somehow got

turned on to the upright bass in high

school. Being a natural, with one of the

best ears in the biz, he soon became one

of the first-call players to accompany

some of the all-time greats—everyone

from Charlie Parker and John Coltrane to

Carmen McRae, Gloria Lynne (all of the

female vocalists raved of his ability to

play behind them and bring out their

finest recorded and live performances),

Dr. Billy Taylor, Dizzy

Gillespie,

Junior Mance,

Barry Harris and Doc Cheatham (those

fantastic Sunday brunches with the sweet

Doc at Sweet Basil’s), just to name a

few. He led and fronted his own groups

towards the later portion of his long

tenure in music, recording many fine CDs

for Matt Dobner’s

Arbor Records that are all available and

should be required for any true jazz

record collector.

I was

lucky enough to finally meet, dine and

catch Earl live in New York playing with

other artists whom I grew to know, love

and call friends, such as Claude

“Fiddler” Williams, Benny Waters, and Al

Casey, to name a few that have passed on

since then. I even got to book Earl at

our Lincoln, Neb., hometown Zoo Bar when

I first started the Berman Music

Foundation. We called the group the New

York All-Stars, which featured my good

buddy Jackie Williams on drums, from the

Mingus days

the now-departed pianist

Jaki

Byard,

trombone master Jimmy

Knepper, and

one of the first appearances of one of

New York’s finest female vocalists

today, Kendra Shank. I have videos of

those shows that, like my interview, I

would love to make public for all his

vast array of friends and fans to

behold. Hanging with Earl and his lovely

wife Lee in my hometown will be

remembered and carried in my heart

forever.

I can

close my eyes and still picture Earl

schlepping his bass all over Manhattan,

dealing with parking his car, getting to

whatever gig he had and, as always,

playing his ass off with more dignity,

finesse, and pure raw talent through his

50s, into his 60s and right up until he

expired at 80.

We

should all be as fortunate to live out

our dreams and goals with such passion

and pleasure. I will always love you,

Earl, and remember the good times for

the rest of my life and enjoy the

incredible legacy of recorded music you

left behind for us all cherish forever.

You truly were one of the best. God

bless you, and rest in peace in jazz

heaven for eternity.

top |

|

|

|

Editor’s Note:

At your request, we will mail a printed version

of the newsletter. The online newsletter also is available at this

website in PDF format for printing. Just click here: Newsletter

|

|

Kansas City,

Mo., is a former bandmate of Butch’s in

The Megatones, a raucous rockabilly and

rhythm ‘n’ blues band that ruled Lincoln

from 1973 to 1976, once opening for

bluesman Freddie King and frequently

holding court in the early days of the

Zoo Bar.

Kansas City,

Mo., is a former bandmate of Butch’s in

The Megatones, a raucous rockabilly and

rhythm ‘n’ blues band that ruled Lincoln

from 1973 to 1976, once opening for

bluesman Freddie King and frequently

holding court in the early days of the

Zoo Bar. one on record,

beginning with a March 1995 booking at

the Zoo Bar in Lincoln. The foundation

brought her back to the Capital City

numerous times to play the Zoo Bar, a

now-defunct club called Huey’s and

eventually a concert performance in

November 2001 at the Lied Center for

Performing Arts, where Allyson was

accompanied by a Kansas City rhythm

section and string players from the

Lincoln Symphony Orchestra.

one on record,

beginning with a March 1995 booking at

the Zoo Bar in Lincoln. The foundation

brought her back to the Capital City

numerous times to play the Zoo Bar, a

now-defunct club called Huey’s and

eventually a concert performance in

November 2001 at the Lied Center for

Performing Arts, where Allyson was

accompanied by a Kansas City rhythm

section and string players from the

Lincoln Symphony Orchestra. resident of New

York City for many years, Dantzler

operates Hot Jazz Management and

Production and has worked with jazz

artists Claude “Fiddler” Williams, Benny

Waters, Earl May and many others.

resident of New

York City for many years, Dantzler

operates Hot Jazz Management and

Production and has worked with jazz

artists Claude “Fiddler” Williams, Benny

Waters, Earl May and many others.

“I was

building a following in New York at that

time,” Shank recalled. “Russ was finding

every way possible for me to sit in with

musicians and meet musicians and expand

my presence on the New York jazz scene.

Butch heard me sing, and I guess he

really liked what he heard.”

“I was

building a following in New York at that

time,” Shank recalled. “Russ was finding

every way possible for me to sit in with

musicians and meet musicians and expand

my presence on the New York jazz scene.

Butch heard me sing, and I guess he

really liked what he heard.” Topeka

Jazz Festival in the late 1990s. After

the Russ Long Trio CD “Never Let Me Go”

had been recorded in 2001, Spaits turned

to Berman as one of several possible

backers who would help to bankroll the

release. Instead, he put up all the

money necessary to issue the release.

Topeka

Jazz Festival in the late 1990s. After

the Russ Long Trio CD “Never Let Me Go”

had been recorded in 2001, Spaits turned

to Berman as one of several possible

backers who would help to bankroll the

release. Instead, he put up all the

money necessary to issue the release. magazine article

that singled out a Lincoln guitar player

for his “letter-perfect vocabulary of

Scotty Moore,” the legendary guitarist

best known for backing Elvis Presley in

the early part of his career.

magazine article

that singled out a Lincoln guitar player

for his “letter-perfect vocabulary of

Scotty Moore,” the legendary guitarist

best known for backing Elvis Presley in

the early part of his career. The recording had been selling well in

the Kansas City area, but Berman wanted

to introduce the music to a Lincoln

audience. He approached the Nebraska

Jazz Orchestra, with whom the BMF had

collaborated in bringing many guest

artists, including saxophonists Bobby

Watson and Greg Abate, trumpeter Claudio

Roditi and singer Giacomo Gates.

The recording had been selling well in

the Kansas City area, but Berman wanted

to introduce the music to a Lincoln

audience. He approached the Nebraska

Jazz Orchestra, with whom the BMF had

collaborated in bringing many guest

artists, including saxophonists Bobby

Watson and Greg Abate, trumpeter Claudio

Roditi and singer Giacomo Gates. Butch was a

big fan of Long's, funding the

release of 2001’s “Never Let Me Go,” a

trio recording with bassist

Spaits and drummer DeMarchi. He was

attracted by Long’s sense of ironic wit,

his bluesy vocalizing, his modesty and,

of course, his diverse talents as

composer, song interpreter, pianist and

singer. An important link in KC jazz

history, Long had known or worked with

some of the region’s greats, including

Eddy “Cleanhead” Vinson, Claude

“Fiddler” Williams, Jay McShann and

Frank Smith.

Butch was a

big fan of Long's, funding the

release of 2001’s “Never Let Me Go,” a

trio recording with bassist

Spaits and drummer DeMarchi. He was

attracted by Long’s sense of ironic wit,

his bluesy vocalizing, his modesty and,

of course, his diverse talents as

composer, song interpreter, pianist and

singer. An important link in KC jazz

history, Long had known or worked with

some of the region’s greats, including

Eddy “Cleanhead” Vinson, Claude

“Fiddler” Williams, Jay McShann and

Frank Smith. Since

my association with the foundation began

as a writer in early 1996, Butch allowed

me to do what I enjoy most, listening to

and writing about jazz. Since the

mid-1980s, I had been doing that for the

Lincoln Journal Star newspaper—at least,

as often as I could justify it to my

editors. Butch let me indulge my passion

for jazz to the extreme, a passion he

shared.

Since

my association with the foundation began

as a writer in early 1996, Butch allowed

me to do what I enjoy most, listening to

and writing about jazz. Since the

mid-1980s, I had been doing that for the

Lincoln Journal Star newspaper—at least,

as often as I could justify it to my

editors. Butch let me indulge my passion

for jazz to the extreme, a passion he

shared. When

Butch launched the foundation in 1995,

he called me at the Journal Star to ask

me to write a story about it. We met for

an interview and I wrote the story, the

first local coverage for the BMF. In

retrospect, it seems inevitable that we

would work together—and play together.

When

Butch launched the foundation in 1995,

he called me at the Journal Star to ask

me to write a story about it. We met for

an interview and I wrote the story, the

first local coverage for the BMF. In

retrospect, it seems inevitable that we

would work together—and play together.![Earl May [Courtesy Photo]](media/308earlmay.jpg) After

losing the wonderful and talented likes

of the late great Frank Morgan and then

Oscar Peterson at the end of 2007, I had

high hopes that 2008 would bring more

joy than sorrow.

After

losing the wonderful and talented likes

of the late great Frank Morgan and then

Oscar Peterson at the end of 2007, I had

high hopes that 2008 would bring more

joy than sorrow.