|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Jane Jarvis Memorial (by Mary Pipher)

Jane Jarvis and the Berman Foundation

|

|

Jane Jarvis Memorial (by Mary

Pipher)

Jane Jarvis and the Berman

Foundation

New-Trad Octet to mix

brass bands and jazz

at upcoming Jazz in

June performance

By Tom Ineck

LINCOLN,

Neb.—More than 30 years have passed since jazz saxophonist Jeff Newell

left Nebraska for more fruitful career opportunities—first in Chicago,

He soon

will return to Lincoln for the first time in four years, leading his

New-Trad Octet for a June 22 performance at this year’s Jazz in June

series. In addition to Newell’s alto sax, the octet also features

trumpet, bass trumpet, tuba, keyboards, bass and drums, a modern brass

band lineup that should be perfect for the outdoor venue, a grassy

sculpture garden just west of Sheldon Museum of Art on the University of

Nebraska-Lincoln’s city campus. Newell last

performed here in January 2006, when he appeared as a guest artist with

the Nebraska Jazz Orchestra, along with fellow NJO alumnus and

saxophonist Frank Basile. On the following night, they performed at the

now-defunct P.O. Pears, fronting a quintet that also consisted of

guitarist Peter Bouffard, bassist Rusty White and drummer Joey Gulizia.

You

can read our review of that evening here. Newell

joined the NJO in the late 1970s, when it was known as the Neoclassic

Jazz Orchestra, and even toured Europe with the big band. In addition to

the 2006 concert, he returned as guest soloist in 1991 and 1994. The

New-Trad Octet has never made the trip to Nebraska, though Newell

Newell

continues to mine those disparate influences for traces of musical

gold. “I’m still

working around the same sort of things. I’m trying to dig a little

deeper into things that are maybe not as close to the surface,” he said

in a recent interview from his Brooklyn home. “I’m getting really

interested in a lot of the music of early brass bands that weren’t

famous. I’m trying to figure out the connection between the early brass

band movement—which, of course, was a huge movement across the

country—and the evolution of jazz.” Making that

connection is an ambitious undertaking, especially considering that

brass bands have a history of more than two centuries and jazz is more

than 100 years old. Both musical styles began in small, unassuming ways,

often played by uneducated musicians, an esthetic that Newell strives to

retain.

But that

wasn’t all. As he began to fit the music into the new harmonic and

rhythmic contexts he envisioned, Newell intentionally altered the tunes,

much as the first musicians must have altered them to conform to their

specific ethnic backgrounds. “We all fit

it into our own cultural context,” he said. “It’s like a game of

telephone. We all hear something different, and then we pull it

together. I’m really interested in how those bands evolved within that

tradition and how that came across in early jazz.” Newell’s

interest in the history of brass bands began in relatively recent years.

Born in Bennington, Neb., a Douglas County town now largely absorbed in

the Omaha metropolitan region, he received a music degree from the

University of Nebraska-Lincoln and pursued graduate studies for a year

before heading to Chicago in 1978 to continue his education in classic

jazz fashion, playing in clubs and at festivals. “When I was

in school back in Nebraska, I just wanted to be a really cool, hip urban

sophisticate, since I came from this small town,” he recalled, laughing.

“But, I was always interested in history and the Civil War and 19th

century life and the westward expansion.” That interest was rekindled in

1994, when he made the leap to New York to study privately with

saxophonists Bunky Green, Joe Daley and, with a fellowship from the

National Endowment for the Arts, David Liebman. He also took up

residence in an classic Brooklyn brownstone, which inspired the CD

title. “Our

apartment is one floor of a building that was built in 1877, with all

this beautiful craftsmanship. When I first moved to Brooklyn, I jokingly

say, I felt like I’d moved into the ruins of a once-great society. When

it was being built, Bennington, Nebraska, was a collection of tents with

a mud street, and here was this ancient civilization that I’d moved

into.” That immersion in the 19th century started him on a

path that led to his current fascination with the evolution of American

music among the working class. “People who

were not trained musicians still had the need inside of them to make

music.” Newell

recently has been sharing the fruit of his research into America’s

musical evolution with students in the Brooklyn school system, through

residencies funded by Chamber Music America and the Doris Duke

Foundation. With an additional grant from a local organization, he is

visiting four different schools. “I’m going

in once a week for six weeks. I’m bringing small groups of musicians,

doing a ragtime trio thing and then I do some blues, and then I bring in

the New-Trad Quartet and we play brass band music. It all culminates

with a concert by the full octet.” So that

he’s able to offer flexible booking arrangements for the large ensemble,

Newell maintains contacts in Chicago as well as New York. The octet that

will appear in Lincoln June 22 also features young Chicago firebrand

Victor Garcia on trumpet, Ryan Shultz on bass trumpet, Mike Hogg on

tuba, Steve Million on keyboards, Neal Alger on guitar, Tim Fox on bass

and Rick Vitek on drums. The Lincoln

audience can expect to hear some Sousa compositions performed in a

manner not usually associated with the military march genre. The concert

also will include some Crescent City sounds and Newell’s take on 19th

century hymns, another historical interest. No family

members remain in Nebraska, but Newell still feels a kinship to his home

state, perhaps most importantly for the early musical bonds he forged

here. Many of those friends will be on hand for his return visit.

Jazz in June again offers five-concert

series By Tom

Ineck LINCOLN,

Neb.—For the second consecutive year, the popular Jazz in June concert

series will feature five Tuesday evening performances. Considering the

hit-an-miss nature of live jazz in Lincoln during the rest of the year,

that is a very good thing for fans of the music. As in

recent years, the Berman Music Foundation will play a major role

in sponsoring the series, now in its 19th year. Each 7 p.m.

concert routinely draws thousands to the sculpture garden outside

Sheldon Museum of Art at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Four of the

five artists in the 2010 lineup have performed in Lincoln and have ties

to the BMF. Trumpeter

Darryl White returns to the stage June 1 with a group resembling

the one he fronted two years ago. Featured again are pianist Jeff

Jenkins of Denver, bassist Craig Akin of New York and drummer Brandon

Draper of Kansas City, Mo. The new addition is veteran saxophonist Dick

Oatts, who over the last 30 years has performed and recorded with such

greats as Lou Rawls, the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra, the Vanguard

Jazz Orchestra, Joe Henderson, Red Rodney, Joe Lovano, Eddie Gomez, and

Jack McDuff. He also has seven recordings under his own name on the

Steeplechase label. In

conjunction with a celebration of

Singer

Angela Hagenbach of Kansas City will front a sextet June 15.

Jeff

Newell’s New-Trad Octet will bring their unique blend of jazz

innovation and brass band tradition to the Jazz in June stage June 22.

Newell last performed here in January 2006, when the saxophonist

appeared as a guest artist with the Nebraska Jazz Orchestra and the

following night with a small group at P.O. Pears. The octet also will feature

Victor Garcia on trumpet, Ryan Shultz on bass trumpet, Mike Hogg on

tuba, Steve Million on keyboards, Neal Alger on guitar, Tim Fox on bass

and Rick Vitek on drums. Read an account of our recent interview with

Newell above.

After five years, jazz and jazz fusion

guitar great Jerry Hahn returns to Lincoln

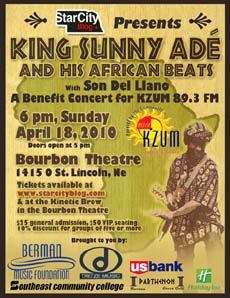

King

Sunny Adé set to rock the Bourbon

Editor's Note:

After two

members of the band were killed in an

auto accident in late March, King Sunny Ade and his African Beats cancelled the first half of

their tour,

including the Lincoln date. Instead, a

free World Music Benefit was held at

the Bourbon

Theatre. Acts included Masoud Mahjouri-Samani of Iran

performing solo on the six-stringed tar; the Alash

ensemble, a quartet of Tuvan throat

singers; Son Del Llano, a local group

performing Cuban son and salsa music;

and Ashanti, an African roots band

playing soca, highlife, reggae and soul

music, including cover versions of King

Sunny Ade songs as a tribute to the

fallen members of his band.

By Tom Ineck

The tour

begins exactly one week earlier, with an

April 11 concert in Montreal. Additional

shows in Toronto, Ann Arbor, Milwaukee,

Chicago, and Minneapolis will prepare

the 16-piece band for its Lincoln

appearance at the Bourbon, 1415 O St.,

where the 6 p.m. concert promises to be

the music event of the year. Doors open

at 5 p.m.

The

Berman Music Foundation is a

principal sponsor of the concert. Local

Cuban and salsa band Son Del Llano will

perform as the opening act.

Click

on the poster to the right for ticket

information.

“When I

met juju music musicians were still

sitting down, with instruments arranged

in front,” Adé says in his official

biography. “I found it hard because I

knew people were not getting full value

for their money. So I started standing

and dancing. I moved the instruments

backwards to allow them enjoy their

Adé and

His African Beats created a worldwide

sensation in the early 1980s with three

recordings on Mango Records—“Juju Music”

(1982), “Synchro System” (1983), and

“Aura” (1984). He was the first African

to be nominated twice for a Grammy

Award, first for “Synchro System” and

most recently for “Odu,” a 1998

collection of traditional Yoruba songs.

In July 2009 he was inducted into the

Afropop Hall of Fame.

After

their Lincoln performance, the African

Beats will continue with scheduled stops

in St. Louis., Houston and New Orleans,

where they will perform April 25 at the

popular New Orleans Jazz and Heritage

Festival. Lincoln is one of the smallest

cities on the six-week tour, which also

includes Seattle, San Francisco, Los

Angeles, San Diego, Washington, D.C.,

Boston, New York City, Philadelphia, and

Atlanta.

The

April 18 Lincoln concert is made

possible by Star City Blog with

additional support from Southeast

Community College, Dietze Music, U.S.

Bank, The Holiday Inn Downtown, and the

Parthenon Greek Taverna and Grill. Net

proceeds will be donated to KZUM.

Tickets are $25 for general admission,

$50 for reserved seats. To

purchase tickets, visit Star City Blog

at

www.starcityblog.com.

By Tom Ineck

LINCOLN, Neb.—Ember Schrag is living,

lively and music-loving proof that one

inspired person with a passion can make

a difference.

Her inspiration was to create a venue

out of her own home, a rental duplex in

Lincoln’s Everett neighborhood that she

christened Clawfoot House. She began

working with Bryan Day, an improviser,

inventor and “sound sculptor” who also

runs Public Eyesore Records. Day had

extensive experience in the music

business worldwide. That led to a series

of house concerts featuring experimental

music, which eventually morphed into

other genres.

“I’m really busy,” she said in a recent

phone interview conducted while Lillian

napped. “But Clawfoot House is so much

fun, and Lincoln really had a need for

this, or it wouldn’t have come out of

nowhere and suddenly become this big

thing.”

Clawfoot House quickly established a

reputation for adventurous booking,

ranging from avant-garde improvisation,

indie-folk and traditional old-timey

artists to a classical quartet, poetry

readings, theater, workshops, lectures,

puppet shows, jugglers and visual

artists. Nothing is out of the question,

as long as it gives voice to artistic

expression, a philosophy summed up in

the Clawfoot mission statement: “We

strive to provide hospitality and fair

pay for talented artists—locals and

those on tour—who perform at Clawfoot

House, as we believe these individuals

deserve support for the risks they take

to make their art and bring it to us.”

It is a mission not unlike that of the

Berman Music Foundation,

established

That common goal recently resulted in a

$2,200 BMF grant to Schrag for a series

of presentations by Seattle-based

singer, songwriter and

multi-instrumentalist Amy Denio, in

collaboration with the UNL Women’s

Center. Denio’s Lincoln stay included a

luncheon presentation on “Music and

Social Change” at the UNL Student Union,

an evening performance at Clawfoot House

and a special edition of the monthly

Clawfoot Salon, featuring Denio in a

lecture and performance. Grace Sankey

Berman attended Denio’s appearance at

the salon and offers her account

elsewhere in this newsletter.

The salon, another Schrag inspiration,

is a gathering of female musicians and

artists who share knowledge, exchange

views, receive feedback on new work and

jam. A lecture series offer aspects of

the history of women in the arts and

skills useful to women artists.

“It seems there aren’t as many

opportunities for female musicians to

learn from other women about technical

stuff and other things. I just thought

that would be really cool to create a

situation where they can learn from each

other and also play music, all together.

The jam, with women, is very different,

very organic. It’s very communal.”

Schrag added an occasional Front Porch

Potluck Grill that brings together

musicians, friends and neighbors for a

common purpose. Recently, she has been

shepherding Clawfoot House through the

arduous process of

“I really like doing it. I really like

curating the series. I like picking

stuff out and bringing good music

together to share it with other people.

And the performers appreciate it. That’s

a big part of the reason why things have

gone so well. Performers really want to

have that kind of experience.

Increasingly, even big-name performers

want to do house shows because you

connect with people better.”

Lincoln’s location, midway between

Denver and Chicago, makes it a logical

stop for artists on the road, a fact

that Schrag and others have capitalized

on. In fact, she now gets at least one

e-mail message every day from musicians

seeking a gig in Lincoln.

“People want to play here,” she said.

“This town can definitely support more

house venues like this.” Last August

alone, Schrag booked eight shows, often

providing lodging and meals for

musicians.

“There was one morning where I was

making breakfast for a dozen men. I used

two dozen eggs and four or five pots of

coffee, and I was having such a good

time! I know what it’s like to be on the

road. We know that people appreciate a

salad and some orange juice because it’s

hard to get good food on the road.”

Once Clawfoot House has 501c3 status, it

will be able to accept tax-deductible

donations to offset some of

Clawfoot House audiences, she said, tend

to be a little younger than the average

LAFTA crowd, alluding to the Lincoln

Association for Traditional Arts, the

city’s longtime folk-music series of

concerts. While some regulars are in

their 50s, most are in their 20s.

“We have a little of the LAFTA

atmosphere, but not the same kind of

music. For the trouble that we’re taking

to open up our home, we want to do

something that’s really unique.” Schrag

has an understanding with her landlord

that allows the live music venue’s

adventurous spirit to flourish.

“Since we have this community aspect,

our landlord has decided that we’re

actually doing the city a favor, we’re

cleaning up the neighborhood and

creating more positive vibes in the

Everett neighborhood. He said he thinks

the city owes us a thank-you, and he’s

very supportive of what we’re trying to

do.”

For more on Clawfoot House, visit

www.clawfoothouse.com. For more on

Schrag’s own music, go to

www.emberschrag.com or

www.myspace.com/smberschragmusic.

Lincoln writer pays tribute to friend

Jarvis

By Mary Pipher

In 1997 Jane Jarvis came to Lincoln with

Benny Waters. I first heard her play

with a trio at the Zoo Bar. Jane was

bedecked in satin and pearls and she

While

Jane was in town, I interviewed her for

my book, “Another Country: Navigating

the Emotional Terrain of Our Elders.”

She had lived a remarkable life in her

81 years. She was the only child of

loving parents. The family lived a

cultured life of art galleries,

classical music and Shakespeare.

However, when Jane was 13 years old, her

parents were killed in a train accident.

After that, she was alone in the world.

She found her peace and happiness in

music.

Jane told me, “Music was a natural part

of me, like my nose. My core identity

was as a musician. My musicality was a

gift and all I had to do was push it

along.” All of Jane’s life, when she

needed sanctuary, music offered her a

safe and cherished place. She said, “I

feel bad for people who have no art in

their lives. I don’t know how they

cope.”

When she was in high school Jane played

piano for a radio station. It was there

that she heard jazz musicians for the

first time. After she listened to them

rehearse,

After our first meeting, Jane and I

remained friends until her death. When I

gave a reading from “Another Country” in

New York, my publisher rented a grand

piano and Jane played at the event. Once

a month, Jane called me from her small

apartment. We would talk for a few

minutes about how happy she was and what

a good life she had lived. During these

calls she laughed a lot and said that

she was at age when “externals don’t

matter. The joy is all inside my head.”

After our talks, she would ask me, “What

do you want to hear today?” I usually

asked for a sad song, such as “Autumn

Leaves” or “Return to Sorrento.” She’d

improvise a long version of whatever I

wanted. Then she’d say, “Now, I am going

to play you a happy song. That’s what I

like to play and you need to cheer up.”

I last saw Jane when I was working in

the city. I visited her at her apartment

on East 50th Street. On my

way up, I passed a flower vendor and I

debated whether to buy her red roses or

white. Finally, I decided to buy a dozen

of each. When Jane’s assistant opened

the door for me, I was hidden behind all

the roses. I told Jane the white roses

were for purity and the red for passion.

She laughed and said she had more of one

virtue than the other.

Jane lay on her small bed in a lovely

silk dressing gown. Her luxuriant silver

hair was brushed down over her

shoulders. She had a window that looked

out on the street. Well-worn biographies

of jazz greats filled her bookcases. We

talked about her happiness and her

acceptance of old age and death as part

of “the great song cycle.” Then she

asked her assistant to help her to the

piano. She treated me to an hour-long

concert of passionate, effervescent

music. Her fingers had forgotten

nothing.

Jane believed in God. “Otherwise,” she

asked, “how do you understand a life

like mine?” She told me, “I embrace all

religions. The prayers of Muslims are

good prayers, and so are those of the

Presbyterians. I can drop into any place

of worship anywhere in the world and

feel at home.” But, Jane did not

anticipate an afterlife. Life on this

earth was miracle enough for her.

Still, it comforts me to imagine her in

heaven. Jane’s heaven would look like a

nightclub in Midtown Manhattan. She and

her favorite musicians would be on a

cramped stage, playing to a packed

house. Jane would be wearing high heels,

a showy velvet dress, and pearls. Her

long blond hair would stream behind her

as she played. Poets, bankers,

publishers, and other jazz musicians

would be in the crowd, dancing or

sitting at little tables with their gin

gimlets and black Russians. The crowd

would be sophisticated enough to applaud

in the right places, to ooh and aah at

the really hot riffs and to hush and

listen when something magic was

happening. By the end of the night,

Jane’s music would soar across the

galaxies and nobody would want to take a

break.

BMF friend Jarvis leaves a legacy of

music

By Tom Ineck

Jane Jarvis, a longtime friend of the

Berman Music Foundation, died Jan. 25 at

the Lillian Booth Actors’ Home in

Englewood, N.J. She was 94.

During their stay, Jarvis also conducted

master classes with students at the

University of Nebraska-Lincoln and at

Park Middle School in Lincoln. In

October 1999, she returned to the city

with trombonist Benny Powell and bassist

Earl May for a benefit performance at

the Cornhusker Hotel, funded in part by

the BMF.

In a 1997 interview, she told me

enthusiastically about her lifelong love

of jazz.

"I'm not

sure when I heard the first jazz

recording. It could have been at an

uncle's home. He had a phonograph. I

didn't have a phonograph when I was a

child. In fact, when I was young, not

every family had a radio. But I did, for

reasons I'm not able to explain, pick up

immediately on everything I heard that

was jazz, and studied it without knowing

I was studying it, and cataloged it in my

mind without being aware that I was

putting it in my musical computer. I

took advantage of everything I heard,

and it influenced my playing."

After leaving Muzak and the New York

Mets in the late 1970s, she began

finding gigs as a jazz pianist,

eventually becoming a regular at Zinno,

a West Village nightclub and restaurant,

where she worked with Milt Hinton and

other jazz bassists. She recorded her

first album as a leader in 1985, the

year she turned 70.

Jarvis had lived at the Lillian Booth

Actors’ Home since she was forced out of

her East Side apartment in 2008 after an

adjacent building was destroyed in a

crane collapse. Butch Berman had

continued to stay in touch with Jane

through the years, right up until his

own death in January 2008.

By Brad Krieger

Present at the gathering were Daniel Nelson, Dylan Nelson, Elizabeth

Nelson, Ruth Ann Nahorny, Brad Krieger, Catherine Patterson, Bob Doris,

and Miles Kildare.

For the past 30-plus years, we would gather at Butch’s house on Saturday

or Sunday for a full-out assault on the Ping Pong table. Butch was

always the gracious host, providing fine wine—and food, if it happened

to be a football Saturday. We kept a running total on who won, and would

have a final tally at the end of the year to see who wound up on top.

In the end, wins and losses were not important, but added to the

excitement of the competition.

Hearing the music, seeing the truth

By Tom

Ineck “Invisible

Man” deals largely in symbolic imagery, the perceptions of others,

self-observance and self-identity, but one way in which Ralph Ellison

examines these visual concepts is through music, its multi-faceted

influence throughout our lives and its impact on our emotions, our

spiritual growth, the way we define ourselves, and our social and

political consciousness. In the course of the novel, he cues important

scenes with references to the melody, harmony, lyrics and rhythms of

song, from such diverse sources as jazz recordings, a Christmas carol

heard from a college chapel, a spontaneous expression of the blues and a

funeral march in Harlem. Attempting

to describe his protagonist’s feelings of invisibility as he

“hibernates” in his underground refuge from the real world, Ellison

invokes the

A choir of

trombones performing “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” inside a college

chapel inspires sadness in the passing listener. You can almost see the

waves of music when Ellison writes, “The sound floats over all, clear

like the night, liquid, serene, and lonely.” Less refined are the

primitive spirituals sung in the chapel by a country quartet: “We were

embarrassed by the earthy harmonies they sang, but since the visitors

were awed we dared not laugh at the crude, high, plaintively animal

sounds Jim Trueblood made as he led the quartet.” In psychic agony after

he rapes his daughter, Trueblood spontaneously raises his voice in song,

beginning with a spiritual. “I don’t know what it was, some kinda church

song, I guess. All I know is I ends up singin’ the blues. I sings me

blues that night ain’t never been sang before, and while I’m singin’

them blues I makes up my mind that I ain’t nobody but myself and ain’t

nothin’ I can do but let whatever is gonna happen, happen.” In the act

of singing this primal music, he acknowledges the baseness of his nature

and its ultimate consequences. Ellison

likens the delivery of a college debater to a brass ensemble, as he

voices his argument in resonating tones, writing “…listen to me, the

bungling bugler of words, imitating the trumpet and the trombone’s

timbre, playing thematic variations like a baritone horn.” During a

choir performance, a girl rises to sing a cappella, “standing high

against the organ pipes, herself become before our eyes a pipe of

contained, controlled and sublimated anguish, a thin plain face

transformed by music.” The loyal followers of a fallen black leader

mourn his passing, “bugles weeping like a family of tender women

lamenting their loved one. And the people came to sing the old songs and

to express their unspeakable sorrow.” Failing to find words to describe

their misery, music becomes the medium through which they articulate the

fullness of their hearts. The quest

to find himself and his place in the world takes the protagonist to

Harlem, where a funeral procession for a black leader is emblematic of

the profound power of music in the lives of black Americans, and of all

people. A lone, elderly male voice and a euphonium render an impromptu

version of “There’s Many a Thousand Gone,” like “two black pigeons

rising above a skull-white barn to tumble and rise through still, blue

air.” Others take up the song, following the old man, “…as though the

song had been there all the time and he knew it and aroused it; and I

knew that I had known it too and had failed to release it out of a

vague, nameless shame or fear. …I looked at the coffin and the marchers,

listening to them, and yet realizing that I was listening to something

within myself.” The old man’s song and its message seem to emanate from

the listeners, as they respond to something beyond religion or politics.

“It was not the words, for they were all the same old slave-borne words;

it was as though he’d changed the emotion beneath the words while yet

the old longing, resigned, transcendent emotion still sounded above, now

deepened by that something for which the theory of Brotherhood had given

me no name.” Ellison’s

protagonist eventually resigns himself to the diversity and absurdity of

life, as in the contradictions inherent in the blues and its myriad

variations or in Louis Armstrong’s evocations of palpable good and evil

when he sings, “Open the window and let the foul air out… Of course

Louis was kidding, he wouldn’t have thrown old Bad Air out,

because it would have broken up the music and the dance, when it was the

good music that came from the bell of old Bad Air’s horn that counted.”

In other words, music tempered by the fires of hell may be the most

heavenly sound of all.

Soon heading south and west for jazz

festivals

By Tom Ineck

As live music goes, 2010 is looking like

an embarrassment of riches. And I’m not

as easily embarrassed as I used to be.

If plans pan out, I will attend the

second weekend of the New Orleans Jazz

and Heritage Festival, April 29-May 2,

and also cover the second week of the

Healdsburg Jazz Festival, June 7-13 in

Northern California, where I had such a

memorable visit last year. The 16-piece

band of King Sunny Adé and his African

Beats will perform April 18 right here

in Lincoln, Nebraska, and in June, five

Tuesday night concerts will continue

this city’s grand tradition of Jazz in

June, the 19th year for this

free series.

After that, who cares?

For example, this year’s festival

features Simon and Garfunkel, B.B. King,

The Allman Brothers, Pearl Jam, King

Sunny Ade and His African Beats, Gipsy

Kings, Widespread Panic, the Four

Freshmen, the Levon Helm Band, Anita

Baker, Keely Smith, The Black Crowes,

Irma Thomas, Lionel Richie, George

Clinton and Parliament/Funkadelic, Jose

Feliciano, Richie Havens and Shawn

Colvin.

Among the artists I hope to hear in my

four-day visit are Van Morrison, Aretha

Franklin, Jeff Beck, comedian Steve

Martin doing his bluegrass thing, Brian

Blade and the Fellowship Band, Dee Dee

Bridgewater celebrating the music of

Billie Holiday, Allen Toussaint, Elvis

Costello, the Wayne Shorter Quartet, the

Dirty Dozen Brass Band, the subdudes,

Ivan Neville’s Dumpstaphunk, and Astral

Project.

The problem with planning your day at

Jazzfest is that it requires maneuvering

among 11 different stages

simultaneously. Conflicts are

inevitable, but that’s part of the fun,

not to mention the great ethnic food,

and the arts and crafts on display and

for sale at the festival, which is

located at the 145-acre county

fairgrounds.

Festival hours are from 11 a.m. until 7

p.m., so much of the morning and evening

hours are free to explore the French

Quarter, dine at one of the many fine

restaurants, go on a riverboat cruise or

take in some more live music at one of

the city’s clubs, which are open to the

wee hours.

The brainchild of founder and

indefatigable director Jessica Felix,

the Healdsburg event is a more

mainstream jazz affair, true to its

mission to present high-quality music

that still challenges and intrigues the

listener. Billed as “the best jazz

festival north of San Francisco,” it

brings world-class jazz to a non-urban

environment where it is presented in a

variety of imaginative venues, from

wine-tasting rooms and open-air greens

to cafes, hotel lobbies and historic

theaters. The year’s festival runs June

4-13.

Expect a full report from New Orleans

and Healdsburg—as well as reviews of

local performances by King Sunny Ade and

the Jazz in June concerts—in our July

online news!

"Jazz Icons" important addition to

BMF library

By Tom Ineck

The most recent addition to the

Berman Music Foundation library may

also be its most important acquisition

ever. It is the first four boxed sets of

DVDs in the ongoing “Jazz Icons” series,

featuring full-length concerts and

studio sessions with the legends of jazz

history. Now totaling more than 30

individual DVDs, the series is a

goldmine of rare recordings of superior

quality, many of them filmed during the

artists’ peak years—the 1950s, 1960s and

1970s.

Each DVD is nicely packaged with a

20-page booklet containing an essay by a

jazz historian, photographs and details

on personnel and session highlights.

They are produced with the full support

and cooperation of the artists’ families

or estates and, in many cases, family

members contribute photographs and write

illuminating forewords. Takashi Blakey

writes about father Art, T.S. Monk

writes about father Thelonious, Paul

Baker writes about father Chet, Cathy

Rich writes about father Buddy, and Lisa

Simone Kelly writes about mother Nina

Simone.

The boxed sets generally run from about

$100 to $150 each. DVDs may also be

purchased separately for about $18.

As jazz critic Nat Hentoff commented,

“This is like the discovery of a bonanza

of previously unknown manuscripts of

plays by William Shakespeare.” I

couldn’t agree more.

The first four boxed sets:

Jazz Icons, Vol. 1 (2006):

Louis Armstrong, Chet Baker, Count

Basie, Art Blakey and the Jazz

Messengers, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy

Gillespie, Quincy Jones, Thelonious

Monk, and Buddy Rich.

Jazz Icons, Vol. 2 (2007):

Dave Brubeck, John Coltrane, Duke

Ellington, Dexter Gordon, Charles

Mingus, Wes Montgomery, and Sarah

Vaughan, plus a bonus disc of

Brubeck, Coltrane, Gordon and

Vaughan.

Jazz Icons, Vol. 3 (2008):

Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans,

Lionel Hampton, Rahsaan Roland Kirk,

Oscar Peterson, Sonny Rollins, and

Nina Simone, plus a bonus disc of

Kirk, Rollins and Simone.

Jazz Icons, Vol. 4 (2009):

Art Blakey, Art Farmer, Erroll

Garner, Coleman Hawkins, Woody

Herman, Anita O’Day and Jimmy Smith,

plus a bonus disc of Garner, Hawkins

and Smith.

Editor’s Note:

At your request, we will mail a printed version

of the newsletter. The online newsletter also is available at this

website in PDF format for printing. Just click here: Newsletter

Feature

Articles

January 2010

Articles 2009

Articles

2008

Articles 2007

Articles 2006

Articles 2005

Articles 2004

Articles 2003

Articles 2002

April 2010

Feature Articles

Music news, interviews, memorials, opinion

![Alto saxophonist Jeff Newell [Courtesy Photo]](media/410Newell1.jpg) then

in New York City—but he has never forgotten the places and people who so

influenced his formative years in the Cornhusker State.

then

in New York City—but he has never forgotten the places and people who so

influenced his formative years in the Cornhusker State. formed

the group some 16 years ago as a vehicle for his arranging skills.

Initially, it blended the traditional “second line” New Orleans brass

band with a modern rhythm section and a fresh approach to harmony and

improvisation. Gradually, Newell’s interest in early brass bands began

to influence the octet’s repertoire, a shift best exemplified on the

band’s 2007 CD “Brownstone,” which occasionally marries Sousa marches

with the exotic rhythms of the Caribbean.

You

can read our review of that CD here.

formed

the group some 16 years ago as a vehicle for his arranging skills.

Initially, it blended the traditional “second line” New Orleans brass

band with a modern rhythm section and a fresh approach to harmony and

improvisation. Gradually, Newell’s interest in early brass bands began

to influence the octet’s repertoire, a shift best exemplified on the

band’s 2007 CD “Brownstone,” which occasionally marries Sousa marches

with the exotic rhythms of the Caribbean.

You

can read our review of that CD here.![The New-Trad Octet [Courtesy Photo]](media/410Newell2.jpg) “Obviously,

a lot of these people in these small towns and little out-of-the-way

places couldn’t read music and they were just learning it by ear, which

is sort of what I tried to incorporate with what I did with the Sousa

marches. I could very easily have gone to the music library and copied

all the stuff out, but instead I got a hold of some CDs of the original

Victrola recordings of Sousa’s band, which were done in the late 1890s.

Then, I transcribed from that.”

“Obviously,

a lot of these people in these small towns and little out-of-the-way

places couldn’t read music and they were just learning it by ear, which

is sort of what I tried to incorporate with what I did with the Sousa

marches. I could very easily have gone to the music library and copied

all the stuff out, but instead I got a hold of some CDs of the original

Victrola recordings of Sousa’s band, which were done in the late 1890s.

Then, I transcribed from that.”

![Otro Mundo [Courtesy Photo]](media/410OtroMundo.jpg) Cuban

culture at Sheldon, the San Diego-based combo Otro Mundo will

perform June 8. Blending the sounds of Brazil, Spain, the United States,

Cuba, Africa, and the Middle East, Otro Mundo is a five-piece outfit

consisting of founders Dusty Brough on guitar, Kevin Freeby on bass, and

Steve Haney on percussion. Flutist and vocalist Rebecca Kleinmann and

drummer Julien Cantelm recently joined the band. Their debut,

self-titled recording was released in February.

Cuban

culture at Sheldon, the San Diego-based combo Otro Mundo will

perform June 8. Blending the sounds of Brazil, Spain, the United States,

Cuba, Africa, and the Middle East, Otro Mundo is a five-piece outfit

consisting of founders Dusty Brough on guitar, Kevin Freeby on bass, and

Steve Haney on percussion. Flutist and vocalist Rebecca Kleinmann and

drummer Julien Cantelm recently joined the band. Their debut,

self-titled recording was released in February.  A

longtime favorite in Lincoln, she has appeared here many times over

the last 15 years, most recently as a guest artist with the

Nebraska Jazz Orchestra at the 2007 Jazz in June. The BMF has followed

her career with enthusiasm, covering performances in Lincoln and in her hometown, as

well as reviewing her recordings. Backing her sultry vocals will be saxophonist

Matt Otto, guitarist Danny Embrey, pianist Roger Wilder, bassist Steve Rigazzi and drummer Doug Auwarter. For

our review of her current release, “The Way They Make Me Feel,”

click

here.

A

longtime favorite in Lincoln, she has appeared here many times over

the last 15 years, most recently as a guest artist with the

Nebraska Jazz Orchestra at the 2007 Jazz in June. The BMF has followed

her career with enthusiasm, covering performances in Lincoln and in her hometown, as

well as reviewing her recordings. Backing her sultry vocals will be saxophonist

Matt Otto, guitarist Danny Embrey, pianist Roger Wilder, bassist Steve Rigazzi and drummer Doug Auwarter. For

our review of her current release, “The Way They Make Me Feel,”

click

here.![Jerry Hahn [Courtesy Photo]](media/1104hahn3.jpg) June

29 with a quartet also featuring Kansas City stalwarts Joe Cartwright on

piano, Tyrone Clarke on bass and Mike Warren on drums. Born in Alma, Neb., the fretmaster grew

up in Wichita, Kan., before moving away for a few decades to record and

tour with saxophonist John Handy, vibraphonist Gary Burton, saxophonist

Bennie Wallace, bassist David Friesen and many others. In the early

1970s, he also led the ground-breaking Jerry Hahn Brotherhood. He

returned to the Wichita area in 2004 and now lives in Lenexa, Kan. The

BMF and Dietze Music House brought Hahn to Lincoln in February 2005 for

guitar workshops and a trio performance at P.O. Pears.

To read an interview we did with Hahn at that time,

click here.

For reviews of those appearances,

click here.

June

29 with a quartet also featuring Kansas City stalwarts Joe Cartwright on

piano, Tyrone Clarke on bass and Mike Warren on drums. Born in Alma, Neb., the fretmaster grew

up in Wichita, Kan., before moving away for a few decades to record and

tour with saxophonist John Handy, vibraphonist Gary Burton, saxophonist

Bennie Wallace, bassist David Friesen and many others. In the early

1970s, he also led the ground-breaking Jerry Hahn Brotherhood. He

returned to the Wichita area in 2004 and now lives in Lenexa, Kan. The

BMF and Dietze Music House brought Hahn to Lincoln in February 2005 for

guitar workshops and a trio performance at P.O. Pears.

To read an interview we did with Hahn at that time,

click here.

For reviews of those appearances,

click here.

![King Sunny Ade and His African Beats [Courtesy Photo]](media/410ksagroup.jpg) LINCOLN,

Neb.—King Sunny Adé and His African

Beats should be thoroughly warmed up and

well settled into their 2010 North

American tour by the time they arrive at

the Bourbon Theatre for an April 18

performance, a benefit for KZUM

Community Radio.

LINCOLN,

Neb.—King Sunny Adé and His African

Beats should be thoroughly warmed up and

well settled into their 2010 North

American tour by the time they arrive at

the Bourbon Theatre for an April 18

performance, a benefit for KZUM

Community Radio. The

undisputed king of “juju music,” Adé has

been honored with titles like “Chairman

of the Board” and “Minister of

Enjoyment” in his home country of

Nigeria, and his crossover popularity

has earned him billing as “the African

Bob Marley.” Juju music is a

dance-inspiring hybrid of western pop

and traditional African music with roots

in the guitar tradition of Nigeria. A

hypnotic blend of electric guitars,

pedal-steel guitar, synthesizers and

multi-layered percussion, it found wide

favor in the 1970s when Adé combined

Yoruba drumming with elements of West

African highlife music, calypso, and

jazz. Adé also brought many other

innovations to the traditional sound and

presentation.

The

undisputed king of “juju music,” Adé has

been honored with titles like “Chairman

of the Board” and “Minister of

Enjoyment” in his home country of

Nigeria, and his crossover popularity

has earned him billing as “the African

Bob Marley.” Juju music is a

dance-inspiring hybrid of western pop

and traditional African music with roots

in the guitar tradition of Nigeria. A

hypnotic blend of electric guitars,

pedal-steel guitar, synthesizers and

multi-layered percussion, it found wide

favor in the 1970s when Adé combined

Yoruba drumming with elements of West

African highlife music, calypso, and

jazz. Adé also brought many other

innovations to the traditional sound and

presentation.![King Sunny Ade on stage [Courtesy Photo]](media/410ksastage.jpg) money

and gave my boys a microphone each to

dance and sing. At that time too,

they were playing only one guitar. I

increased to two, three, four, five and

the present six. I dropped the use of

the accordion and introduced keyboards,

the manual jazz drum and now the

electronic jazz drum. I introduced the

use of pedal steel otherwise known as

Hawaiian guitar, increased the

percussion aspect of the music, added

more talking drums, introduced computer

into juju music and de-emphasized the

use of high tone in the vocals.”

money

and gave my boys a microphone each to

dance and sing. At that time too,

they were playing only one guitar. I

increased to two, three, four, five and

the present six. I dropped the use of

the accordion and introduced keyboards,

the manual jazz drum and now the

electronic jazz drum. I introduced the

use of pedal steel otherwise known as

Hawaiian guitar, increased the

percussion aspect of the music, added

more talking drums, introduced computer

into juju music and de-emphasized the

use of high tone in the vocals.”

![Ember Schrag [Photo by Grace Sankey-Berman]](media/410Schrag2.jpg) In

Schrag’s case, that passion is for

making music and sharing the music of

others with the Lincoln community. For

seven years, she had been guiding her

own music career and—like many other

local artists—struggling to find venues,

booking gigs, traveling and recording. A

North Platte native and UNL graduate who

majored in English and music, Schrag

considered a move to the Pacific

Northwest to immerse herself in

Portland’s music scene, but she decided

to stay in Lincoln to await the arrival

of daughter Lillian.

In

Schrag’s case, that passion is for

making music and sharing the music of

others with the Lincoln community. For

seven years, she had been guiding her

own music career and—like many other

local artists—struggling to find venues,

booking gigs, traveling and recording. A

North Platte native and UNL graduate who

majored in English and music, Schrag

considered a move to the Pacific

Northwest to immerse herself in

Portland’s music scene, but she decided

to stay in Lincoln to await the arrival

of daughter Lillian. ![Clawfoot House at 1042 F St. [Courtesy Photo]](media/410Clawfoot2.jpg) With

Day’s connections and experience gained

by promoting her own shows over the

years, Schrag turned 1042 F St. into a

house concert stage for other musicians.

She opened the doors to the public in

January 2009, promising and delivering a

homey space with low admissions and

high-quality acts. In its first year,

Schrag booked some 45 acts there, a

notable accomplishment considering that

she still performs, works full-time at

the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and

is raising an infant daughter.

With

Day’s connections and experience gained

by promoting her own shows over the

years, Schrag turned 1042 F St. into a

house concert stage for other musicians.

She opened the doors to the public in

January 2009, promising and delivering a

homey space with low admissions and

high-quality acts. In its first year,

Schrag booked some 45 acts there, a

notable accomplishment considering that

she still performs, works full-time at

the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and

is raising an infant daughter.![Chiara String Quartet performs at Clawfoot House [Courtesy Photo]](media/410Clawfoot4.jpg) 15

years ago: “The foundation realizes the

difficulties involved in maintaining a

career as an artist and will assist

those individuals who yearn to create

according to their own hearts and not

simply to become a commercial success.

The foundation, touched by the spirit of

all the musicians who seek to present

and preserve American music, will strive

diligently to illuminate the pathway to

a long-lasting, deep appreciation of

music, in all its forms and hues.”

15

years ago: “The foundation realizes the

difficulties involved in maintaining a

career as an artist and will assist

those individuals who yearn to create

according to their own hearts and not

simply to become a commercial success.

The foundation, touched by the spirit of

all the musicians who seek to present

and preserve American music, will strive

diligently to illuminate the pathway to

a long-lasting, deep appreciation of

music, in all its forms and hues.”![Schrag has occasional Front Porch Potluck Grill concerts during the summer months [Courtesy Photo]](media/410Clawfoot3.jpg) incorporating

as a non-profit organization. Perhaps

most important in directing an intimate,

low-budget, live music venue with little

hope of ever turning a profit, Schrag

loves her work.

incorporating

as a non-profit organization. Perhaps

most important in directing an intimate,

low-budget, live music venue with little

hope of ever turning a profit, Schrag

loves her work.![Ember Schrag and her band perform at Clawfoot House [Courtesy Photo]](media/410Clawfoot1.jpg) those

expenses and even expand the series of

house concerts. Schrag and Day already

are studying the possibility of bringing

in experimental, avant-garde music

artists from New York, Mexico City,

China, Chicago and Philadelphia.

those

expenses and even expand the series of

house concerts. Schrag and Day already

are studying the possibility of bringing

in experimental, avant-garde music

artists from New York, Mexico City,

China, Chicago and Philadelphia.

![Mary Pipher [Courtesy Photo]](media/410pipher.jpg) played piano with great skill and heart.

In their first set, the group brought

down the house. At the break, Jane shook

hands, signed CDs and connected easily

with her fans. But, after a short while,

she hunted down Benny’s manager and

said, “Let’s get going.” He said, “You

get a half hour break.” Jane said

firmly, “I don’t want a long break. I

came to play.”

played piano with great skill and heart.

In their first set, the group brought

down the house. At the break, Jane shook

hands, signed CDs and connected easily

with her fans. But, after a short while,

she hunted down Benny’s manager and

said, “Let’s get going.” He said, “You

get a half hour break.” Jane said

firmly, “I don’t want a long break. I

came to play.”![Jane Jarvis [Courtesy Photo]](media/410Jarvis.jpg) she asked if she could join

them in a song. They were bemused, but

agreed. She said, “Let’s play what you

last played.” She kept up with them.

Later she played organ for baseball

games in Shea Stadium. She was a vice

president and production manager for Muzak and traveled all over the world to

record music. Her greatest musical honor

was to be included in the illustrious

group of old players called The

Statesmen of Jazz.

she asked if she could join

them in a song. They were bemused, but

agreed. She said, “Let’s play what you

last played.” She kept up with them.

Later she played organ for baseball

games in Shea Stadium. She was a vice

president and production manager for Muzak and traveled all over the world to

record music. Her greatest musical honor

was to be included in the illustrious

group of old players called The

Statesmen of Jazz.

![Butch Berman and Jane Jarvis in 1997 [File Photo]](media/397JarvisBB.jpg) The

Berman foundation first brought Jarvis

to the attention of jazz fans in

Lincoln, Neb., in 1997, when she

appeared on March 9 at the Zoo Bar,

sharing the billing with saxophonist

Benny Waters, who was 95 at the time.

Jane was a relatively young and

sprightly 81. Indeed, she boasted of

being a month younger than my mom when

they were introduced during

intermission.

The

Berman foundation first brought Jarvis

to the attention of jazz fans in

Lincoln, Neb., in 1997, when she

appeared on March 9 at the Zoo Bar,

sharing the billing with saxophonist

Benny Waters, who was 95 at the time.

Jane was a relatively young and

sprightly 81. Indeed, she boasted of

being a month younger than my mom when

they were introduced during

intermission.![Jane Jarvis conducts workshop at UNL [File Photo]](media/397Jarvis.jpg) Born

Jane Nossett Jarvis on Oct. 31, 1915,

Jane formed a jazz band in her native

Indiana as a teenager, and continued to

work as a jazz pianist from her mid-60s

into her 90s. But for more than two

decades she was best known as a ballpark

organist, first with the Braves at

County Stadium in Milwaukee, then at

Shea Stadium from 1964 to 1979, mixing

jazz tunes like “Scrapple from the

Apple” with more conventional fare like

“Take Me Out to the Ballgame.” She also

worked for Muzak, eventually becoming

vice president of programming and

recording and hiring jazz musicians like

Lionel Hampton and Clark Terry to record

sessions that produced some swinging

“elevator music.”

Born

Jane Nossett Jarvis on Oct. 31, 1915,

Jane formed a jazz band in her native

Indiana as a teenager, and continued to

work as a jazz pianist from her mid-60s

into her 90s. But for more than two

decades she was best known as a ballpark

organist, first with the Braves at

County Stadium in Milwaukee, then at

Shea Stadium from 1964 to 1979, mixing

jazz tunes like “Scrapple from the

Apple” with more conventional fare like

“Take Me Out to the Ballgame.” She also

worked for Muzak, eventually becoming

vice president of programming and

recording and hiring jazz musicians like

Lionel Hampton and Clark Terry to record

sessions that produced some swinging

“elevator music.”

![Brad Krieger, Dylan Nelson, Bob Doris, Daniel Nelson, and Miles Kildare gather for annual tournament [Courtesy Photo]](media/410pingpong.jpg) The

Second Annual Butch Berman Memorial Ping Pong tournament was hosted by

Daniel Nelson, a long-time friend of the Berman Music Foundation.

The

Second Annual Butch Berman Memorial Ping Pong tournament was hosted by

Daniel Nelson, a long-time friend of the Berman Music Foundation.

The following essay was written for a class in

African-American literature that I’m taking at the University of

Nebraska-Lincoln. I wrote it after reading Ralph Ellison’s masterful and

highly acclaimed novel “Invisible Man,” published in 1952. It was one of

four short papers required by course instructor Megan Peabody. Since it

deals with the use of music as a symbol throughout the book, I

thought it appropriate for BMF readers. I also liked the idea of

recycling the essay for a broader audience. I have altered the scholarly

formatting and page citations for a more journalistic approach.

The following essay was written for a class in

African-American literature that I’m taking at the University of

Nebraska-Lincoln. I wrote it after reading Ralph Ellison’s masterful and

highly acclaimed novel “Invisible Man,” published in 1952. It was one of

four short papers required by course instructor Megan Peabody. Since it

deals with the use of music as a symbol throughout the book, I

thought it appropriate for BMF readers. I also liked the idea of

recycling the essay for a broader audience. I have altered the scholarly

formatting and page citations for a more journalistic approach. ![Louis Armstrong in a more serious mood [Courtesy Photo]](media/410Armstrong.jpg) power of jazz as trumpeter Louis Armstrong sings and plays

Fats Waller’s bluesy lament “What Did I Do to Be So Black and Blue,”

writing, “Perhaps I like Louis Armstrong because he’s made poetry out of

being invisible. I think it must be because he’s unaware that he is

invisible. And my own grasp of invisibility aids me to understand his

music.” Like Armstrong’s syncopated rhythm, being invisible, he notes,

“gives one a slightly different sense of time, you’re never quite on the

beat.” He equates the visual with the aural when he writes, “…You hear

this music simply because music is heard and seldom seen, except by

musicians. Could this compulsion to put invisibility down in black and

white be thus an urge to make music of invisibility?” Even in the

quandary of his invisibility, he defines the dilemma in terms of the

racial colors of black and white.

power of jazz as trumpeter Louis Armstrong sings and plays

Fats Waller’s bluesy lament “What Did I Do to Be So Black and Blue,”

writing, “Perhaps I like Louis Armstrong because he’s made poetry out of

being invisible. I think it must be because he’s unaware that he is

invisible. And my own grasp of invisibility aids me to understand his

music.” Like Armstrong’s syncopated rhythm, being invisible, he notes,

“gives one a slightly different sense of time, you’re never quite on the

beat.” He equates the visual with the aural when he writes, “…You hear

this music simply because music is heard and seldom seen, except by

musicians. Could this compulsion to put invisibility down in black and

white be thus an urge to make music of invisibility?” Even in the

quandary of his invisibility, he defines the dilemma in terms of the

racial colors of black and white.

The

Crescent City Jazzfest, now in its 41st

year, celebrates a range of musical

styles far beyond jazz and those other

ethnic sounds native to New

Orleans—Cajun and zydeco music. The city

also has a unique take on the blues,

rock ‘n’ roll, r&b, soul and gospel

music, and all are represented on stage.

But even though its emphasis remains on

the area’s considerable musical

heritage, Jazzfest has grown in scope to

include hugely popular artists of many

traditions.

The

Crescent City Jazzfest, now in its 41st

year, celebrates a range of musical

styles far beyond jazz and those other

ethnic sounds native to New

Orleans—Cajun and zydeco music. The city

also has a unique take on the blues,

rock ‘n’ roll, r&b, soul and gospel

music, and all are represented on stage.

But even though its emphasis remains on

the area’s considerable musical

heritage, Jazzfest has grown in scope to

include hugely popular artists of many

traditions. ![Esperanza Spaulding will perform at Healdsburg Jazz Festival. [Courtesy Photo]](media/410Esperanza.jpg) While

at the 12th Annual Healdsburg

Jazz Festival in early June, I hope to

enjoy the music of pianist George

Cables, bassist Charlie Haden with Ravi

Coltrane and Geri Allen, bassist and

singer Esperanza Spaulding, and pianist

Jason Moran and the Bandwagon, featuring

guitarist Bill Frisell. Making the

experience even more significant is that

I will share it with old friends, some

of whom live near Healdsburg and others

who will travel from San Diego.

While

at the 12th Annual Healdsburg

Jazz Festival in early June, I hope to

enjoy the music of pianist George

Cables, bassist Charlie Haden with Ravi

Coltrane and Geri Allen, bassist and

singer Esperanza Spaulding, and pianist

Jason Moran and the Bandwagon, featuring

guitarist Bill Frisell. Making the

experience even more significant is that

I will share it with old friends, some

of whom live near Healdsburg and others

who will travel from San Diego.

![]() Reelin’

in the Years Productions has been

seeking out and licensing live

recordings from all over the world,

releasing annual sets since 2006. Many

of the performances had never been

released on DVD and, in some cases, were

never even broadcast. Many were created

for TV programs in Scandinavia, Western

Europe and England, places where jazz

has traditionally found more public

support than the music does in the very

country in which it was born.

Reelin’

in the Years Productions has been

seeking out and licensing live

recordings from all over the world,

releasing annual sets since 2006. Many

of the performances had never been

released on DVD and, in some cases, were

never even broadcast. Many were created

for TV programs in Scandinavia, Western

Europe and England, places where jazz

has traditionally found more public

support than the music does in the very

country in which it was born. ![]() Unlike

the flawed approach of Ken Burns’ “Jazz”

series, the beauty of these

recordings—and their historical and

educational value—is that they eschew

critical narration and lecture for

simple, straightforward performance.

They allow the viewer to draw his or her

own conclusions by simply listening and

watching these great artists at work.

Unlike

the flawed approach of Ken Burns’ “Jazz”

series, the beauty of these

recordings—and their historical and

educational value—is that they eschew

critical narration and lecture for

simple, straightforward performance.

They allow the viewer to draw his or her

own conclusions by simply listening and

watching these great artists at work.