|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Berman Foundation opens to raves

|

|

Berman Foundation opens to raves

New

Berman museum-offices open to raves

By Tom Ineck

LINCOLN, Neb.—More than 1,000 people

visited The Burkholder Project in just

two hours during the April 3 First

Building owner and artist Anne

Burkholder said the attendance exceeded

all expectations. The previous record

for a gallery walk was about 600 people. She attributed the

huge increase, in large part, to the BMF’s grand opening. Indeed, it seemed

at times that all 1,000 visitors had

simultaneously converged in the

Skylight Gallery studio apartment,

making conversation—and even movement—a

challenge.

If brave enough or inquisitive enough to

wade into the assembled snarl, they were

greeted by BMF representatives happy to

explain the history of the foundation

and its long and supportive presence on

the Lincoln music scene and beyond.

After lunch, we toured the new BMF

facilities, most of the consultants

seeing the space for the first time.

Everyone agreed that the museum’s

relocation from Butch’s house to the

lively downtown area was a move sure to

heighten visibility and further the

foundation’s mission to educate,

entertain and celebrate through music.

“Butch would have loved this!” was a

frequent refrain among those who knew

him best. Not only would he have

appreciated the genuine show of support

and friendship that the spectacular

grand-opening attendance represented,

but he would have beamed at the prospect

that the foundation he created might

reach a new audience who would learn to

love music almost as much as he did.

Friends come out for BMF grand opening

Don and Jill Holmquist

Friends of the

BMF gather in main room

Hors d'œuvres in the glow of the neon

sign

Joyce Latrom and

Wade Wright

Gerald and Leslie

Spaits Chris Lohry, Russ Dantzler and Dad

Peter and Jane Reinkordt (right)

Susan and John

Horn

Kim Jasung, Rose Spencer, Grace,

and Joseph Akpan

Berman advisors gather for the first time

in the new BMF offices

Tad Fraizer,

Devrah Lehner, Algis

Lakaitis and Deb

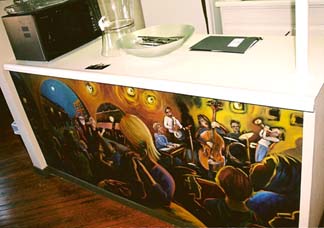

Higuchi "Jazz Club" by Leora Platte was

commissioned by the Berman Music

Foundation and unveiled at the grand

opening.

Tom Ineck, Dan Demuth, Kay Davis, Leslie

Spaits and Gerald Spaits

Advisors meet for lunch

before grand opening.

Artist receptions continue a grand

tradition By Grace

Sankey-Berman Because of

his appreciation for music, and the love and respect he had for

musicians, Butch always entertained artists at his house after concerts

sponsored by the Berman Music Foundation. He wanted to give them

a place to relax after playing and talk about the music with people of

like minds. So we

continued that tradition with post-concert receptions for some of the

2009 Jazz in June artists at the new BMF offices at The Burkholder

Project in the

It was nice

to watch the musicians go through the music collection looking for their

favorite artists or just some obscure artists they had not heard in a

long time. Bassist Roger Barnhart of ZARO was fascinated with album

covers. He talked about how artistic some of the albums were—or were

not. Lincoln native Andrew Vogt was pleasantly surprise to hear his CD

“Action Plan” playing in the

When Kendra

Shank and her band arrived at the reception, they were tired and hungry.

She said singing was “an athletic event” and was so happy to have some

vegetables. Kendra had previously played twice for Jazz in June and was

thrilled to be back for the third time. She said the experience felt

like making love to 7,000 people. Her record “Afterglow” was playing on

the stereo. She smiled when she heard it and said she had not heard it

in a long time. She talked about how her music had changed over the

years and how much she continues to evolve as an artist. Drummer Tony

Moreno was fun. He could not

We were

also delighted to host Bill Wimmer and Project Omaha after their

arguably best concert of the season. Guitarist Dave Stryker and his

extended family and friends were in attendance. So also were the great

drummer Victor Lewis and his manager Joanne Klein. I was thrilled for

the chance to talk to Victor Lewis. We reminisced about the times we

spent with Butch in his basement. He was particularly glad that the

foundation continues to keep the music alive.

Jazz in

June is an 18-year tradition that brings thousands of Lincoln residents

together every Tuesday in June. The Berman Music foundation is proud to

be a long-time supporter of this family-friendly event, and we are happy

to show our appreciation to the musicians who entertain us every year. Thanks to

all the local artists, friends and fans of jazz who attended the

receptions. We appreciate your support.

"New Harmonies" tour celebrates roots

music By

Tom Ineck

The Berman Music Foundation

recently awarded a $2,000 grant to the Nebraska Humanities Council for

“New Harmonies: Celebrating American Roots Music,” a touring exhibition

sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution.

“New Harmonies” examines the

growth of American music, which is as rich and eclectic as the country

itself. American music reveals distinct cultural identities

With its financial support, the BMF

recognizes the connection between the roots music theme of “New

Harmonies” and its own mission “to protect and promote unique forms of

American music.”

“With the

support of the Berman Music Foundation and other sponsors, the Nebraska

Humanities Council is able to bring these exhibitions to small, often

under-served, museums across the state,” said NHC Program Officer Mary

Yager. “Sponsorship allows the NHC to pay the rental fee of the

exhibition and provide it at no cost to the small museums. If a museum

were to bring in a small traveling exhibit on its own it would cost the

museum thousands of dollars.”

In

conjunction with the exhibition’s stop in Kearney, an Aug. 15 lecture

and recital program will explore the evolution of

country music—one of the musical forms explored in the “New Harmonies”

exhibit—from its beginnings in 1920s American folk music through early

Jimmie Rodgers, Bob Wills’ western swing, and Sons of the Pioneers

through classics by Hank Williams and Ernest Tubbs to the classic

country era of the 1950s and 1960s. The

exhibition of “New Harmonies” in Valentine will coincide with Old West

Days, Oct. 1-4, where cowboy poets, musicians, and storytellers will

entertain and attendees can explore the exhibit which includes a panel

celebrating the singing cowboys Gene Autry, Roy Rogers and Tex Ritter. Loves Jazz

& Arts Center will screen their recently produced documentary “All That

Omaha Jazz,” host a jazz and blues band, a gospel singer or group, a

Native American dance troop, and a contemporary music-spoken

word-hip-hop group.

California trip again combines life's

pleasures By Tom

Ineck OCCIDENTAL,

Calif.—I hope you’re as fortunate as I am to have dear friends in a

place that you love to visit. If so, you know the satisfaction of

combining two of life’s pleasures, travel and companionship.

The stars

were properly aligned on this occasion, with Wade celebrating a birthday

on the day of my arrival. We met before noon and grabbed a sunny table

outside the café. We were later joined by Terri Hinte, a Bay area legend

among jazz writers and jazz musicians for her longtime work as writer,

editor and publicist with Fantasy Inc. and currently fronting her own

jazz publicity agency and

The three

of us had a delightful meal, complete with decadent desserts, and

conversation that ranged over many mutual interests. More than three

hours later, I rose to head out of town, with great thanks and happy

birthday wishes to Wade. My West

Coast odysseys always include a few days in Occidental, a wonderful

Sonoma County village of about 1,500 people 60 miles north of the city.

I still had a couple of hours to make my rendezvous with a friend there,

so I drove—somewhat recklessly—up the winding road to the 2,500-foot

peak of Mount Tamalpais and along the scenic coastal highway, an

exhilarating ride after my long, cramped flight and sedentary urban experience. Founded in

1876, Occidental first earned its reputation as a railroad and

timber-cutting center, with six sawmills operating in the area by

1877. Some of the

But, like

any city that leaves a lasting impression on the visitor, it is the

people who make Occidental a favorite return destination. In my case,

those people are Joe Phillips, Nikki Farrer, their son, Jobee, and their

many friends. Joe and I have known each other since the late 1960s, when

we both attended Pius X High School in Lincoln. Joe, Nikki and I later

lived together as part of a communal group that settled for a while in

Bisbee, Ariz. Later, I returned to Nebraska and they moved to

California, eventually migrating up the coast to the country of wine,

rivers and redwood forests. We have

never lost touch, though we go months without speaking to each other and

years between my visits. It is the essence of friendship that when we do

gather, the old familiar thoughts and feelings, the easy camaraderie,

come rushing back, almost as though we had never parted ways. Perhaps

the 1,500 miles that separate us actually make us closer.

Over the

years, my trips to Northern California have often coincided with

concerts and festivals, including the Russian River Jazz Festival in

1987, the Cotati Jazz Festival in 1993, the San Francisco Jazz Festival

in 1996, a concert by the Frank Zappa tribute band Project Object at the

Mystic Theater in Petaluma in 2002, and this year’s Healdsburg Jazz

Festival, featured

here. The

Healdsburg gathering was especially memorable, as Jobee, now 34, and his

girlfriend, Jen, joined us for an afternoon of Brazilian jazz in a small

city ballpark. The weather was ideal and the music was joyous and

inspired. Two nights later, Joe, Nikki, Jobee and I took in another jazz

concert at the Palette Art Café, where we shared plates of appetizers

and consumed a few local brews.

As we reach

our late 50s and early 60s and many of our contemporaries take their

leave of this life, our visits take on a new urgency. From now on, an

annual trip to this neck of the woods is not out of the question. In

fact, it seems downright mandatory.

Kendra Shank returns to Lincoln June 16

By Tom Ineck

LINCOLN, Neb.—In a 2009 Jazz in June

concert series that features several

artists with direct ties to Nebraska,

even New Yorker Kendra Shank refers to

her recent appearance as “coming

home.”

This time, the Kendra Shank Quartet

arrived in the midst of a busy touring

schedule behind her new CD “Mosaic,”

released April 14. That alone raised the

excitement level in eager anticipation,

not least of all because Shank, over the

last decade, has developed a fruitful

relationship with the same core group of

musicians, pianist Frank Kimbrough,

bassist Dean Johnson and drummer Tony

Moreno.

“Over time, we’ve gotten to know each

other so well that it’s like it’s

telepathic,” Shank said in a recent

phone conversation from her home. “I

don’t have to say anything. I don’t give

much direction. We’re collaboratively

creating these arrangements. Usually it

starts with a seed idea of mine.” That

creative germ, she said, is just “a

stepping-off point” to group

communication and personal expression.

Her bandmates appreciate that.

“Part of their joy in being a part of

this band is that they’re really free. I

bring these musicians into the group

because I love their playing and I like

their

After so many years together, “a huge

level of trust” is implicit in every

performance. “I know these are musicians

who listen, who play sensitively, and

who are going to make esthetic choices

in the moment that serve the music well

and that make sense.”

The mutual trust transferred well to the

recording studio, where Shanks also

added longtime collaborators Billy

Drewes on saxophones and clarinet and

Ben Monder on guitar. Unlike their

previous outing, “A Spirit Free: Abbey

Lincoln Songbook,” the new release had

no obvious theme. Instead, it was a

return to Shank’s earlier records, a

varied, well-paced collection of tunes

that appealed to her. Only later did she

recognize that the 11-track “Mosaic”

does have an overarching theme—the many

aspects of love.

“So Far Away,” Carole King’s story of

lovers separated by space and time,

opens the CD. “Life’s Mosaic” updates

the Cedar Walton instrumental with

lyrics by John and Paula Hackett that

turn it into a plea for global

community, another form of love. Irving

Berlin’s “Blues Skies” is re-imagined

with Shank’s

Long a devotee of the 13th

century mystic poet Rumi, Shank included

two tunes inspired by him. On one, she

combined the verse of “Water from Your

Spring” with the Victor Young standard

“Beautiful Love” and indicated to the

band that the mood should be that of a

Zen garden. Several years ago, she

suggested that composer Kirk Nurock read

some Rumi, after which he presented

Shank with “I’ll Meet You There,” using

texts adapted from the poet that espouse

both spiritual and romantic love. In

appreciation, Nurock dedicated the song

to Shank, and it closes the CD.

Shank credits the band’s long-standing

monthly booking at the 55 Bar in New

York for the workshop esthetic that

allows and encourages musicians to work

up new material over a long period of

time. The creative evolution of

“Reflections in Blue/Blue Skies” is a

case in point.

“I had just done ‘How Deep is the Ocean’

and usually another song will pop right

into my head, and then I’ll call the

tune,” she explained. “Well, nothing

came to mind. I’m just sitting there

with a black head. I’m completely

blank.” Rather than panic, she leaped

into the void with a spontaneous, a

cappella vocal improvisation that

finally resolved in an oblique reference

to the Irving Berlin classic, which was

not even in her repertoire. The

improvised lyric of “Reflections” deals

with love lost and regained, setting the

emotional stage for “Blues Skies.”

Other songs included on “Mosaic” are

Johnny Mandel’s “The Shining Sea,” a

song of loving and longing with lyrics

by Peggy Lee, Cole Porter’s immortal

“All of You” and Bill Evans’ “Time

Remembered,” with lyrics by Paul Lewis.

Shank was thoroughly primed for her

Lincoln appearance, having already

performed the new repertoire in more

than a dozen cities since early April,

including Seattle, Portland, Ore., San

Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego,

Cincinnati, Richmond, Ken., Cleveland,

Cambridge, Mass., and at the Jazz

Standard in New York City.

Gehring returns home to share "Radio

Trails"

By Tom Ineck

Gehring’s return as a

musician to his home town was a long time

coming. A varied life as player, teacher

and tour manager took him to

Minneapolis, Paris and back to the Twin

Cities before he finally wound up on the

East Coast in 2000. But he fondly

remembers the last time he performed in

Lincoln, a jazz-rock fusion gig nearly

20 years ago at Duffy’s Tavern, just

around the corner from the Zoo Bar, a

nationally known blues club that he

recognizes as a Lincoln institution.

“I had

a little fusion band when I left

Lincoln, playing with a couple guys,

just a bassist and a drummer," he said

in a recent phone interview from his

Brooklyn home. "We were

just breaking into the scene of jazz,

playing whatever we could. Since I kind

of came out of the punk-rock scene,

Duffy’s was more my crowd of people.”

In 1989, Gehring’s

influences were guitarists John

McLaughlin, Mike Stern and John

Scofield. A second-year sociology major

at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln,

he dreaded the research work, preferring

to hang out with musicians, usually in

challenging open-stage settings.

“At the time, I was

taking guitar lessons from Steve Lawler

at Dietze. Once you start playing jazz

on the guitar—or any instrument, for

that matter—it’s addictive. It’s been 20

years now, and the love for it increases

and increases.”

Throughout his

career, Gehring has found himself, like

many Americans, returning to the music

that shaped his early years. In fact,

that music was the impetus behind his

new recording, "Radio Trails."

“This was a huge

concept record, but the whole thing came

together because I really need to purge

the ‘70s out of my system. I’m a product

of the ‘70s—I was born in ’68—and I

listened to the radio constantly in the

‘70s. You turned on the radio. That’s

how you found your music. Lincoln was a

town where music was everywhere. It

informed everything you did, everything

you went to, everything you wore.

Everything you talked about seemed to be

centered around music. No wonder I

became a musician.”

“After a while, you

say to yourself, ‘Why does everything

end up sounding like a ‘70s TV theme?

Why is everything sounding like “Cosby”

or something that may have been on “Flip

Wilson”? What’s going on here? I need to

work through this.’”

With “Radio Trails,”

Gehring’s addresses his obsession with

the ‘70s head-on. From conception to

realization, the recording was almost 10

years in the making, says Gehring.

“What I wanted to do

was take the songs of the ‘70s that had

the biggest influence on me, and then I

stretched beyond that to take some of

the singer-songwriters that came out of

those bands, and then let’s take the

originals that we want—that are

influenced by that sound—and put them on

the record. And, let’s write lyrics to

one, and make it a unique, sincere

homage to that period.”

With that in mind,

much thought went into choosing and

sequencing each of the 10 tunes on the

CD, from Supertramp’s “Take the Long Way

Home” to The Carpenters’ “Yesterday Once

More,” the concluding track.

“It IS yesterday once

more. Nothing has changed. Nothing has

changed politically. Economically, it

seems we are repeating the same

behavior. We’ve come a long way, but so

much has been coming back.”

Among the other

notable songs of the ‘70s are “Big

Brother” by Stevie Wonder, “Motions

Pictures” by Neil Young and “She,” a

soulful country ballad by Gram Parsons

and Chris Etheridge, which has also been

covered by David Clayton-Thomas, Emmylou

Harris and Norah Jones.

As a nod to the

Brazilian Tropicalia movement of the

late ‘60s and early ‘70s, Gehring also

chose C. Coqueijo Costa’s “E Preciso

Perdoar” and Vinicius Cantuaria’s “Amor

Brasiliero.” But the concept album is

anchored most obviously by the original

tunes, especially Gehring’s haunting

“Radial Tales” and the anecdotal “That

was the Story.”

To do justice to

these tunes, Gehring assembled

Commonwealth, a group of compatible

musicians and friends, including Bill

Carrothers, the German-born Matthias

Bublath and Aussie Sean Wayland on

keyboards; Dan Gaarder on vocals; Ronen

Itzik and Georg Mel on drums and

percussion; and Michael O’Brien playing

bass on three tracks. Wayland also

co-wrote and contributes a fine vocal to

“That was the Story.”

“I really

hand-selected these guys,” Gehring said.

“Carrothers I wanted there to make the

artistic calls on the music. I didn’t

want to do that. I’m in there to play.”

Mixing unique, swinging interpretations

of pop standards with a sincere love for

the music and a healthy dose of humor,

the end result is what Gehring describes

as “big-fun jazz.”

Bublath, Gaarder and

Twin Cities drummer Joey Van Phillips

accompanied the guitarist on their

summer tour to the Heartland.

In the last of a

series of momentous coincidences,

Gehring learned of the death of Butch

Berman in January 2008 from an online

article that documented Butch’s life as

a radio deejay, musician, music

collector and all-around music advocate.

That was enough to convince Gehring to

dedicate “Radio Trails” to Butch.

“My deepest

appreciation goes out to the Berman

Music Foundation for their contribution

and support of this album,” he writes in

the liner notes. “May the joy and spirit

of music for which Butch Berman worked

so tirelessly to perform and promote

continue in the hearts of those he

supported and beyond.”

The only time Gehring

had a chance to hang out with Butch was

in April 1998, when the guitarist was

tour manager for an innovative jazz trio

called A Band in all Hope, consisting of

pianist Bill Carrothers, drummer Bill

Stewart and saxophonist Anton Denner.

The BMF sponsored a performance by the

group at Westbrook Recital Hall in

Lincoln, and before the show members and friends of the

BMF, Gehring and the band gathered for a

relaxing dinner and conversation.

Gehring’s return to

Nebraska to share “Radio Trails” with

his live audiences not only brings

the CD project full circle but

re-establishes his early ties to Lincoln

and the BMF, a long way home but a

serendipitous trail, indeed.

Bad

Plus defies category, challenges

listeners

By Tom Ineck

When a jazz group has

the good fortune—and tenacity—to stay

together for nearly a decade, it

develops a personal and musical rapport

that is well-nigh telepathic. So it is

with The Bad Plus, an acoustic piano

trio that defies both categorization and

the critics.

On its five previous

CDs, the Twin Cities trio has

occasionally dabbled in audacious

covers—Black Sabbath, Blondie, David

Bowie and Burt Bacharach, among

others—but never to this extent. Since

the CD’s release in November, the band

and Lewis have spent a lot of time on

the road, a tour that brought them to

Omaha for an April 24 performance at the

1200 Club in the Holland Center for

Performing Arts.

In a recent phone

conversation during the band’s week-long

hiatus at home, Anderson attempted to

answer the persistently nagging

question, “How would you describe what

you guys do, and how the heck do you do

it?”

“The best description

that somebody came up with was

avant-garde populism,” he said. “It’s

just the result of the three of us

coming together in a situation that we

created so that we could all be

ourselves.”

The three of them

first came together as The Bad Plus

almost 20 years ago, but subsequently

went their separate ways before

reforming in 2001. Their major-label

debut, “These Are the Vistas,” was

released in 2003, and they have never

looked back.

Anderson cites their

common Midwestern roots as a significant

factor in their musical compatibility.

He and King hail from Minneapolis, while

Iverson is from Menominee, Wis.

“I think we share a

certain tribal language with each other

and a certain sense of the surreal, but

also a love of song, a love of clarity

in music and we try to just bring it all

together and allow that personal voice

to come through.”

From its inception, a

large part of that personal voice has

been composed of irreverence and a

tongue-in-cheek approach to familiar

melodies. But the end result is never

disrespectful.

“We have a basic

respect for all that music,” Anderson

said. “It starts and ends there. We do

these things out of respect because we

feel like there’s something to be said,

with any of this music. That sets the

whole process on that course. That’s why

it works together. We don’t do things

that we aren’t connected to in some

way.”

Two brief liner notes

on the band’s first CD illustrate the

guiding principles. Their take on Kurt

Cobain’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” is

described as “lovingly deconstructed,”

whereas the cover of Deborah Harry’s

“Heart of Glass” is called “ruthlessly

deconstructed.” Anderson explains:

“You’ve got to have

some ruthlessness. You can’t treat all

these things like precious pearls. We’re

all just here to try to bash out some

form of personal expression. That can

take a lot of different forms, but you

can’t exclude ruthlessness.”

Whether inspired by

love or ruthlessness, the music exudes

good humor and a wildly adventurous

spirit.

“We definitely

believe in enjoying what we’re doing,

and I hope that comes across in our

performances and recordings,” Anderson

said. “At the same time, we take music

very seriously. The fun part is all the

possibilities. Certainly, music should

have the capacity to put a smile on your

face.”

Anderson said their

famous eclecticism was not a product of

financial need, as in some cases where a

young musician capable of playing in

different styles is more likely to make

a decent living from his craft.

“That’s never really

been the issue. It’s more that we’re

just genuinely interested in all these

different things. Our gateway into

music, in general, was just listening to

rock radio and playing in rock bands.

We’ve all played jazz in every

imaginable stylistic situation. I have a

degree in classical music performance.

Ethan has played in tango bands. We’ve

written music for dance. We’ve kind of

done it all, and I think that’s part of

the sound of the band. You have all of

this authentic experience in all these

different things, so when there’s a rock

beat in The Bad Plus it’s a real rock

beat.”

One of the best

examples of that “real rock beat” is the

band’s incredible nine-minute recording

of Anderson’s intense, stop-time

masterpiece “Physical Cities,” from the

2007 release, “Prog.” King’s drum

bombast rivals Led Zeppelin’s

magisterial tub-thumper John Bonham.

Anderson describes the tune’s evolution.

“It actually started

at a sound check. Dave and I just

started improvising this thing. We

thought it was cool and thought it kind

of sounded—like you said—like John

Bonham. Also, in that tune I was

thinking about some things that certain

metal bands do, these intense, heavy

rhythmic figures that are not

immediately discernible. You don’t know

exactly what’s going on and kind of get

lost in the mantra of it.”

King is responsible

for recruiting Lewis for the latest

project.

“Dave and Wendy

played together about 10 years ago, with

her bands, and they had a really good

creative relationship,” Anderson

explained. “I had heard a little bit of

that music, and I always thought about

her voice since I heard a couple demo

CDs. We were thinking a lot about who to

get for this recording, what kind of

qualities that person should have. Wendy

came up and it just seemed like the

right move to make. Ethan had to just

trust us. We didn’t even get together

with her to try it out. We just gave her

a call and said, ‘Hey, do you want to

make this record?’ and took a chance,

and it worked out great. She’s been

incredible to work with.”

Was there any

apprehension among the three long-time

bandmates about the prospect of working

with a vocalist for the first time?

“Yeah, a little bit,

at first, just because none of us had

worked with Wendy in this kind of a

context. She didn’t know what to expect.

None of us really knew what to expect or

how it would work. We just started from

zero, getting together in a room and

working out these arrangements. It’s not

a process that completely falls into

place, even when it’s just the three of

us, so we were definitely taking a

chance with it.”

From the start, Lewis

was an integral part of the recording,

from choosing the tunes to working up

the arrangements.

“We definitely wanted

her to feel like a part of the process

and to sing songs that she felt good

about singing, even though we did force

her to do a couple that she wasn’t at

first that enamored with, but now she

admits that she likes doing them.” One

of those, the 1950s doo-wop classic

“Blue Velvet,” didn’t make the cut to

CD, but appears on the vinyl version of

“For All I Care.”

As usual, the songs

underwent a thorough process of

deconstruction and reconstruction, but

Anderson said the evolution of each

track was unique, from Nirvana’s

depressing grunge rocker “Lithium” to

the alt country drone of Wilco’s “Radio

Cure” to the romantic light pop of the

Bee Gees’ “How Deep Is Your Love?” to

the slick rock bombast of Heart’s

“Barracuda” to Miller’s traditional

country weeper “Lock, Stock and

Teardrops.”

“Each one of these

tunes is its own world. In doing this

kind of music, there is no real road map

for how you approach it. We kind of just

take every one as it comes and try to

agree on what’s the essence of the song

and try to make it our own. We were

still tweaking arrangements when we were

in the studio, so we spent a little time

working out some details.”

So how did

Stravinsky, Babbitt and Ligeti find

their way to the recording studio?

“It was just

something that we happened upon as we

were conceiving the record. Ethan was

practicing these classical music

excerpts for something that he was

doing. One day Dave started playing

along and we all kind of looked at each

other and said, ‘Hey, why don’t we do

this in The Bad Plus?’ From there, it

just made sense to us to put that music

on the record.”

For listeners who may

not be comfortable with instrumental

jazz, the lyrical content may bring new

followers to The Bad Plus, but that was

never by overt design.

“I think all of our

music has crossover potential, but what

do I know?” Anderson joked. “That’s not

the intention with which it was made. If

it gets us a few more fans, that’s

great. It’s a noble challenge to try to

present your music and get as many

people to enjoy it as possible. It’s

very open. We’re not sitting there in

our exclusive clubs saying, ‘You’re not

going to get this.’ You know what I

mean? We’re making music that we want to

reach out to people.”

While reaching out to

new listeners, the new record also has

drawn some criticism.

“It has been a very

polarizing record,” Anderson admitted.

“We’ve gotten some really extreme

reactions on both ends, but we’re kind

of used to that, at this point.”

The best testimonial

to the phenomenal appeal of The Bad Plus

is in their wide-ranging audience.

“Our audience is

quite eclectic,” Anderson said. “We have

as many hard-core traditional jazz fans

as we do young indie rock fans. One of

the great things that we see is parents

and their kids coming to the show and

everybody enjoying it. That’s important

and it makes us feel good. It’s not

music that’s targeting a certain

generation or a certain clique of

people.”

Editor’s Note:

At your request, we will mail a printed version

of the newsletter. The online newsletter also is available at this

website in PDF format for printing. Just click here: Newsletter

Feature

Articles

April

2009

January 2009

Articles

2008

Articles 2007

Articles 2006

Articles 2005

Articles 2004

Articles 2003

Articles 2002

July 2009

Feature Articles

Music news, interviews, opinion

![The public converges on BMF offices during grand opening. [Photo by Dan DeMuth]](media/709grandopen15.jpg) Friday Gallery Walk, a record attendance

for the monthly event and a landmark

occasion for the Berman Music

Foundation. For the first time in its 14

years, the BMF museum and offices were

combined under one roof, and everyone

came out to see it and celebrate the

legacy of Butch Berman.

Friday Gallery Walk, a record attendance

for the monthly event and a landmark

occasion for the Berman Music

Foundation. For the first time in its 14

years, the BMF museum and offices were

combined under one roof, and everyone

came out to see it and celebrate the

legacy of Butch Berman.![John Carlini and Bill Wimmer provide music for grand opening. [Photo by Richard S. Hay]](media/709grandopen17.jpg) Despite the claustrophobic conditions, a

celebrative mood prevailed both inside

the museum-office space and outside the

room, where saxophonist Bill Wimmer and

keyboardist John Carlini provided live

jazz in the narrow hallway of the

Skylight Gallery. As music reverberated

throughout the building, art patrons

became aware that something exciting was

happening. Many who were previously

unfamiliar with the Berman foundation

made their way to the upper level for a

look.

Despite the claustrophobic conditions, a

celebrative mood prevailed both inside

the museum-office space and outside the

room, where saxophonist Bill Wimmer and

keyboardist John Carlini provided live

jazz in the narrow hallway of the

Skylight Gallery. As music reverberated

throughout the building, art patrons

became aware that something exciting was

happening. Many who were previously

unfamiliar with the Berman foundation

made their way to the upper level for a

look. Earlier in the day, trustee Tony Rager

gathered the BMF consultants for a

pre-opening lunch and meeting at Lazlo’s

restaurant and brewpub, directly across

the street from The Burkholder. They had

come from as far away as San Francisco

(Wade Wright) and New York City (Russ

Dantzler), as well as

Fayetteville, Ark. (Kay Davis), Pueblo, Colo.

(Dan DeMuth),

Kansas City, Mo. (Gerald and Leslie

Spaits), and Lincoln (Grace

Sankey-Berman and Tom Ineck. All had

been close, trusted friends of founder

Butch Berman, so it was with mixed

feelings of joy and sorrow that we

shared a meal and conversation that

often involved fond reminiscences of

Butch.

Earlier in the day, trustee Tony Rager

gathered the BMF consultants for a

pre-opening lunch and meeting at Lazlo’s

restaurant and brewpub, directly across

the street from The Burkholder. They had

come from as far away as San Francisco

(Wade Wright) and New York City (Russ

Dantzler), as well as

Fayetteville, Ark. (Kay Davis), Pueblo, Colo.

(Dan DeMuth),

Kansas City, Mo. (Gerald and Leslie

Spaits), and Lincoln (Grace

Sankey-Berman and Tom Ineck. All had

been close, trusted friends of founder

Butch Berman, so it was with mixed

feelings of joy and sorrow that we

shared a meal and conversation that

often involved fond reminiscences of

Butch.![Framed drawing of Butch Berman as "Jazz Santa" oversees the main room. [Photo by Richard S. Hay]](media/709grandopen19.jpg) That sentiment was confirmed when doors

opened to the public at 7 p.m. and

visitors began to arrive in waves,

swelling to a critical mass about 8:30

p.m. and dwindling to a few friends and

jazz enthusiasts after the doors had

officially closed at 9 p.m.

That sentiment was confirmed when doors

opened to the public at 7 p.m. and

visitors began to arrive in waves,

swelling to a critical mass about 8:30

p.m. and dwindling to a few friends and

jazz enthusiasts after the doors had

officially closed at 9 p.m.

![Project Omaha and friends gather for portrait. [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/709receptionomaha.jpg) Haymarket

District. Local artists, friends of jazz and fans also were invited.

Among those who attended were Ed Love, music director of the Nebraska

Jazz Orchestra, and his lovely wife, Loretta, coordinator of Jazz in

June Martha Florence, Lincoln jazz keyboardist John Carlini, Sheldon

Museum of Art collections curator Sharon Kennedy, Sheldon events

coordinator Laurie Sipple, Star City Blog publisher Dennis Kornbluh and

his father, David, and friends and fans like Ruthann Nahorny and

Mary Berry.

Haymarket

District. Local artists, friends of jazz and fans also were invited.

Among those who attended were Ed Love, music director of the Nebraska

Jazz Orchestra, and his lovely wife, Loretta, coordinator of Jazz in

June Martha Florence, Lincoln jazz keyboardist John Carlini, Sheldon

Museum of Art collections curator Sharon Kennedy, Sheldon events

coordinator Laurie Sipple, Star City Blog publisher Dennis Kornbluh and

his father, David, and friends and fans like Ruthann Nahorny and

Mary Berry.![Kendra Shank Quartet (from left) Frank Kimbrough, Tony Moreno, Kendra and Dean Johnson [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/709receptionshank.jpg) music

room. Drummer and percussionist Oscar Dezoto said he remembered every

song on the album, even though he did not play on it. I enjoyed

listening to Dezoto talk about the various people he has played with

over the years, including an African musician from Senegal.

music

room. Drummer and percussionist Oscar Dezoto said he remembered every

song on the album, even though he did not play on it. I enjoyed

listening to Dezoto talk about the various people he has played with

over the years, including an African musician from Senegal.![Grace Sankey-Berman and Victor Lewis [Photo by Devrah Lehner]](media/709receptionomaha3.jpg) get

over how vast the music collection is, and he kept saying, “This is

nuts!” as he looked through the records.

get

over how vast the music collection is, and he kept saying, “This is

nuts!” as he looked through the records.![Luigi Waites and Joanne Klein [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/709receptionomaha2.jpg) Victor’s

friend from Omaha the great musician Luigi Waites also attended.

Watching the interaction between the two artists was priceless. They

seemed to enjoy each other’s company. Percussionist Joey Gulizia said

there was so much music he would like to come back sometime to have a

better look. We like to hear that because the collection is a great

resource and we encourage musicians and educators to take advantage of

it.

Victor’s

friend from Omaha the great musician Luigi Waites also attended.

Watching the interaction between the two artists was priceless. They

seemed to enjoy each other’s company. Percussionist Joey Gulizia said

there was so much music he would like to come back sometime to have a

better look. We like to hear that because the collection is a great

resource and we encourage musicians and educators to take advantage of

it.

Through

its Museum on Main Street program, the Smithsonian makes specially

designed traveling exhibitions available only through state humanities

councils. By year’s end, “New

Harmonies” will have visited six communities in Nebraska, completing the

state tour with a stay Oct. 18 through Dec. 31 at Loves Jazz & Arts

Center in Omaha. It will be at the Trails and Rails Museum in Kearney

July 30-Aug. 29 and at the Cherry County Historical Society Museum in

Valentine Sept. 3-Oct. 11. Earlier this year, it had extended runs in

Alliance, Cambridge and Columbus.

Through

its Museum on Main Street program, the Smithsonian makes specially

designed traveling exhibitions available only through state humanities

councils. By year’s end, “New

Harmonies” will have visited six communities in Nebraska, completing the

state tour with a stay Oct. 18 through Dec. 31 at Loves Jazz & Arts

Center in Omaha. It will be at the Trails and Rails Museum in Kearney

July 30-Aug. 29 and at the Cherry County Historical Society Museum in

Valentine Sept. 3-Oct. 11. Earlier this year, it had extended runs in

Alliance, Cambridge and Columbus.!["New Harmonies" celebrates American music, including the blues and jazz. [Courtesy Photo]](media/709harmoniesoswald.jpg) and records

the histories of peoples from Africa, Europe, Asia and the Americas.

"New Harmonies" explores how our country’s ongoing cultural process has

made America the birthplace of great music—from jazz and blues to

country western, folk and gospel.

and records

the histories of peoples from Africa, Europe, Asia and the Americas.

"New Harmonies" explores how our country’s ongoing cultural process has

made America the birthplace of great music—from jazz and blues to

country western, folk and gospel.![Gospel singer Mahalia Jackson [Courtesy Photo]](media/709harmoniesmahalia.jpg) Yager said

such sponsorships also allow the NHC to provide a stipend to each museum

to help them to promote the exhibition, arrange special programming

related to the topic of the exhibition, and create a complimentary

exhibit of local interest. Among the goals of Museum on Main Street are

to help small museums build their visitor base and membership, and help

them increase their capacity to develop exhibits, marketing and

programming.

Yager said

such sponsorships also allow the NHC to provide a stipend to each museum

to help them to promote the exhibition, arrange special programming

related to the topic of the exhibition, and create a complimentary

exhibit of local interest. Among the goals of Museum on Main Street are

to help small museums build their visitor base and membership, and help

them increase their capacity to develop exhibits, marketing and

programming.

![Wade Wright and Terri Hinte outside Cafe Divine [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/709tomfoolery1.jpg) So

it is every couple of years, when I fly—or occasionally drive—from

Nebraska to Northern California. In late May, I

touched down at the San Francisco International Airport in time to pick

up my rental car and have a leisurely lunch in the city with friends

before heading further north. Wade Wright, a Berman Music Foundation

advisor and manager of Jack’s Record Cellar in the city, also helps his

brother at Café Divine, where “heavenly cuisine” is the byword. Butch

Berman recommended the place in a column he wrote several years ago,

and I wanted to check it out in person.

So

it is every couple of years, when I fly—or occasionally drive—from

Nebraska to Northern California. In late May, I

touched down at the San Francisco International Airport in time to pick

up my rental car and have a leisurely lunch in the city with friends

before heading further north. Wade Wright, a Berman Music Foundation

advisor and manager of Jack’s Record Cellar in the city, also helps his

brother at Café Divine, where “heavenly cuisine” is the byword. Butch

Berman recommended the place in a column he wrote several years ago,

and I wanted to check it out in person.![Terri Hinte and Tom Ineck finally meet outside Cafe Divine. [Photo by Wade Wright]](media/709tomfoolery5.jpg) managing

the career of saxophonist Sonny Rollins. As a jazz writer, I had

corresponded with Terri by mail and e-mail for some 25 years, but we had

never met until now.

managing

the career of saxophonist Sonny Rollins. As a jazz writer, I had

corresponded with Terri by mail and e-mail for some 25 years, but we had

never met until now. ![Nikki Farrer enjoying the 2009 Healdsburg Jazz Festival [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/709tomfoolery2.jpg) original

19th century buildings still stand, including the Union

Hotel, built in 1879. Today it houses one of the best Italian

restaurants in the region, and its saloon is a favorite watering hole

for area residents. Just across the street is Negri’s, which combines

Italian cuisine with a lively bar and occasional live music.

original

19th century buildings still stand, including the Union

Hotel, built in 1879. Today it houses one of the best Italian

restaurants in the region, and its saloon is a favorite watering hole

for area residents. Just across the street is Negri’s, which combines

Italian cuisine with a lively bar and occasional live music.![Joe Phillips, Jobee Farrer and Nikki Farrer at the Palette Art Cafe [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/709tomfoolery3.jpg) It

certainly helps that we are all inquisitive, broad-minded fans of music,

from rock to jazz to world music. That love of music has long been our

common ground, so it’s a joy when we can share live performances.

It

certainly helps that we are all inquisitive, broad-minded fans of music,

from rock to jazz to world music. That love of music has long been our

common ground, so it’s a joy when we can share live performances.![Wildflower on the rugged coast above Bodega Bay [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/709tomfoolery4.jpg) On

my final full day in the area, Joe and I took a road trip to another

favorite place, the rugged, beautiful coast at Bodega Bay, where Alfred

Hitchcock filmed much of “The Birds.” It was a glorious spring day, so

we hiked the hillsides above the bay, which were profuse with aromatic

wildflowers. It was the perfect end to another memorable stay.

On

my final full day in the area, Joe and I took a road trip to another

favorite place, the rugged, beautiful coast at Bodega Bay, where Alfred

Hitchcock filmed much of “The Birds.” It was a glorious spring day, so

we hiked the hillsides above the bay, which were profuse with aromatic

wildflowers. It was the perfect end to another memorable stay.

![Shank at 2007 Jazz in June performance [File Photo]](media/707shank1.jpg) Shank’s

June 16 concert was her quartet’s

third at the outdoor venue, having

previously performed in 2004 and 2007.

The singer first appeared on a Lincoln

stage way back in 1995, when the Berman

Music Foundation brought her to the Zoo

Bar as part of an all-star lineup that

included Claude “Fiddler” Williams,

pianist Jaki Byard, bassist Earl May and

drummer Jackie Williams.

Shank’s

June 16 concert was her quartet’s

third at the outdoor venue, having

previously performed in 2004 and 2007.

The singer first appeared on a Lincoln

stage way back in 1995, when the Berman

Music Foundation brought her to the Zoo

Bar as part of an all-star lineup that

included Claude “Fiddler” Williams,

pianist Jaki Byard, bassist Earl May and

drummer Jackie Williams. ![The Kendra Shank Quartet at Jazz in June 2007 [File Photo]](media/707shank6.jpg) creative

ideas, so I just let them express

themselves. That’s the whole point. Jazz

is an improvisational art form, so let

that happen. That’s what makes this

music exciting. You’ve got four people,

each of which has their own life

experience and their own personality and

their own technical ability and their

own harmonic sense and rhythmic sense.

So each person has something really

valuable to contribute.”

creative

ideas, so I just let them express

themselves. That’s the whole point. Jazz

is an improvisational art form, so let

that happen. That’s what makes this

music exciting. You’ve got four people,

each of which has their own life

experience and their own personality and

their own technical ability and their

own harmonic sense and rhythmic sense.

So each person has something really

valuable to contribute.” original

improvisation “Reflections in Blue,” and

Charlie Chaplin’s forlorn “Smile” is

ingeniously combined with “Laughing at

Life.” Kimbrough’s own “For Duke” is

endowed with a beautiful lyric of love

by his wife, composer, vocalist and poet

Maryanne De Prophetis.

original

improvisation “Reflections in Blue,” and

Charlie Chaplin’s forlorn “Smile” is

ingeniously combined with “Laughing at

Life.” Kimbrough’s own “For Duke” is

endowed with a beautiful lyric of love

by his wife, composer, vocalist and poet

Maryanne De Prophetis.

![Ray Gehring [Courtesy Photo]](media/709gehring2.jpg) LINCOLN,

Neb.—Guitarist Ray Gehring has

proved that you CAN go home again. He

traveled with his band from Brooklyn,

N.Y., for gigs May 20 in Minneapolis,

May 21 at the Saddle Creek Bar in Omaha

and May 22 at the Zoo Bar in Lincoln,

the city where he spent his formative

years as a music fan and a fledgling

musician.

LINCOLN,

Neb.—Guitarist Ray Gehring has

proved that you CAN go home again. He

traveled with his band from Brooklyn,

N.Y., for gigs May 20 in Minneapolis,

May 21 at the Saddle Creek Bar in Omaha

and May 22 at the Zoo Bar in Lincoln,

the city where he spent his formative

years as a music fan and a fledgling

musician.  Even

in his jazz songwriting, Gehring began

to hear evidence of his immersion in

1970s pop-culture radio and TV.

Even

in his jazz songwriting, Gehring began

to hear evidence of his immersion in

1970s pop-culture radio and TV.

![The Bad Plus with singer Wendy Lewis (left) [Courtesy Photo]](media/709badplus1.jpg) On

their latest venture, “For All I Care,”

pianist Ethan Iverson, bassist Reid

Anderson and drummer Dave King have

taken another bold leap forward by

adding vocalist Wendy Lewis on a

recording that eschews original material

for a mix of classic pop songs by

artists ranging from Nirvana and the Bee

Gees to Pink Floyd and Roger Miller.

Tastefully sprinkled among these tracks,

as though they were “palate cleansers,”

are the band’s unique instrumental

interpretations of modern classical

melodies by Igor Stravinsky, Gyorgy

Legeti and Milton Babbitt.

On

their latest venture, “For All I Care,”

pianist Ethan Iverson, bassist Reid

Anderson and drummer Dave King have

taken another bold leap forward by

adding vocalist Wendy Lewis on a

recording that eschews original material

for a mix of classic pop songs by

artists ranging from Nirvana and the Bee

Gees to Pink Floyd and Roger Miller.

Tastefully sprinkled among these tracks,

as though they were “palate cleansers,”

are the band’s unique instrumental

interpretations of modern classical

melodies by Igor Stravinsky, Gyorgy

Legeti and Milton Babbitt.