Abate all-star quartet

plays Lincoln June 10

By Tom Ineck

Greg Abate remains a

resident of the Providence, R.I., area where he was

reared, a lifestyle choice that might have meant obscurity

for a lesser artist. The intrepid saxophonist, however, has achieved

a body of work and a level of recognition that ensures his livelihood,

in Europe as well as the United States.

His lyrical flights,

biting tone and rhythmic sophistication draw comparisons to Charlie

Parker, but Abate also echoes the more tranquil ruminations of Paul

Desmond. He has a broad repertoire of standards at his nimble fingertips,

but he also is a first-class composer. His most recent release, “Evolution,”

is a showcase for his writing talents, containing nine original tunes.

![Greg Abate [Photo by Rich Hoover]](media/abate1.JPG) Abate brings all of

this, and an all-star quartet, to Lincoln for a June 10 performance at

Jazz in June in the sculpture garden of the Sheldon Art Gallery on the

University of Nebraska-Lincoln downtown campus. Accompanying Abate on that

trip are pianist Phil DeGreg, bassist Harvie S and drummer Billy Hart. Abate brings all of

this, and an all-star quartet, to Lincoln for a June 10 performance at

Jazz in June in the sculpture garden of the Sheldon Art Gallery on the

University of Nebraska-Lincoln downtown campus. Accompanying Abate on that

trip are pianist Phil DeGreg, bassist Harvie S and drummer Billy Hart.

In a phone

interview from St. Paul, Minn., where he was performing a two-night

stand at the Artists’ Quarter, Abate speculated about his choice to

live in Rhode Island rather than the Big Apple.

“Living in New York

may have brought me to other areas,” he said. “Maybe I would be better

known now, if I did live there. I’ve always wondered about that. I really

don’t know if it has hindered me, at all.”

One thing is sure. Whether

Abate plays in St. Paul or Duluth, Minn.; Moscow, Idaho; a small

town on Cape Cod or Lincoln, Neb., audiences are enthusiastic and

perhaps more appreciative than jaded jazz aficionados in New York

City, San Francisco or Boston.

“I’ve had a very good

response. People like my stuff, and I’m really glad to be able to play.”

Abate himself listens to his own playing with a critical ear.

“I was listening to

one of my CDs, “Straight Ahead” (from 1992), and I could really hear how

much I’ve evolved since then. I’ve still got these recordings, and people

are buying my old stuff and I don’t sound anything like that. My playing

is really starting to fall into place, where I can really have more control

over what I want to do.”

Artistic control is

especially evident in his last several recordings, where Abate has been

moving from standards to a more personal expression. Never one to rely

solely on the melodies most familiar to his audience, he has either chosen

more obscure compositions (Hank Mobley’s “This I Dig of You,” Monk’s “Ask

Me Now”) or written them all himself, as with “Evolution.”

That 2002 recording

features the same lineup that will be in Lincoln, with the exception of DeGreg,

who subs for pianist James Williams. The fact that Abate wrote all nine

tunes in the year preceding the sessions gives the recording an immediacy

often missing in CDs that are cobbled together from many different sources

and different time frames. The fact that Abate first put pen to paper on

Sept. 11, 2001, for the ballad “Dearly Departed,” gives the recording an

especially timely poignancy. The tune is jointed dedicated to those who

lost their lives in the terrorist attack and to Abate’s parents, who died

in 1998 and 1999.

Adding to the personal

touch on “Evolution,” Abate doubled the alto with tenor sax or flute

on several tracks.

“The overdubs were easy

to play,” he said. “The solos were all live, in sequence. I didn’t

do overdubbed solos.” He had first attempted the effect while practicing

with a four-track recorder at home—overdubbing piano and three saxes—but

this was the first time he applied the technique for commercial release.

“You can do that because

you know how you play, you know your feeling and your habits. When

you play with the other track, you can most likely hit the same type

of rhythm and the same type of articulation.”

His own agent, road

manager and paymaster, Abate negotiates occasional solo jobs at festivals

and clubs in Europe. His trips to France, England, Germany, Switzerland,

Spain and Russia have taken him far from home, allowing jazz fans worldwide

to experience his incredible talents. When at home, he teaches in the jazz

program at Rhode Island College.

Thirty years ago, Abate

gathered valuable experience in the Ray Charles Orchestra (succeeding

David “Fathead” Newman). He finally took the helm as a leader in the

1990s, recording several fine releases on various small labels since

1991. A multi-instrumentalist, Abate plays tenor, flute, and soprano,

but it is the alto horn for which he is known.

Abate’s sidemen on his

trip to Nebraska also deserve wider attention. DeGreg is a wonderful

straight-ahead pianist who is on the faculty of the University of

Cincinnati Conservatory of Music. He has at least three recordings

as a leader.

Another native New Englander,

Harvie S is perhaps best known for his series of duet recordings

and performances with singer Sheila Jordan. His experience ranges from

gigs with Al Cohn and Zoot Sims, Mose Allison and Chris Connor in Boston

to work with Jackie & Roy, Jackie Paris, Thad Jones, Gil Evans, Lee

Konitz, David Friedman, and Steve Kuhn since he moved to New York City

in 1972. He also has headed his own groups, including the fusion band Urban

Earth.

Hart, a Washington,

D.C., native, is a much-in-demand drummer who is capable of playing in

a variety of settings. While still in the nation’s capital, he worked with

saxophonist Buck Hill and singer Shirley Horn. He later traveled with the

Montgomery Brothers, Jimmy Smith and Wes Montgomery. He was a member of

Herbie Hancock’s sextet in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, and played regularly

with McCoy Tyner and Stan Getz throughout the ‘70s, in addition to extensive

freelancing.

|

Concert

Preview

BMF helps book another Jazz in June series

|

By

Tom Ineck

Again the Berman Music Foundation has provided the consulting

expertise and financial support to help produce another top-flight

Jazz in June concert series, featuring artists with varying styles

and broad audience appeal.

The free outdoor concerts are held every Tuesday in June beginning

at 7 p.m. in the Sculpture Garden just west of the Sheldon Art Gallery

on the University of Nebraska-Lincoln downtown campus. The concerts

routinely draw audiences of more than 1,000 people and often several

thousand.

The BMF has worked extensively in the past with the first

two artists, and Jazz has carried CD reviews of all four. The series begins

June 3 with the return of Norman Hedman’s Tropique. Saxophonist Greg Abate

will front a bop quartet June 10. UNL trumpet professor Darryl White will

head a sextet also featuring alto saxophonist Bobby Watson on June 17, and

mandolin virtuoso Don Stiernberg will appear with his quartet June 24.

![Norman Hedman [Photo by Rich Hoover]](media/hedman1.jpg) Percussionist Norman Hedman, a longtime friend, consultant

and associate of

the BMF, has appeared in the Jazz in June

lineup before, but this time his New York City-based tropical jazz

group, Tropique, will feature a slightly different lineup of players.

Hedman’s combo plays an engaging blend of warm-climate dance rhythms,

including salsa, Latin jazz, bomba and samba. A world-class conguero,

Hedman has a percussion style influenced by Cal Tjader and Armando Peraza.

The BMF is the chief sponsor of this concert. Percussionist Norman Hedman, a longtime friend, consultant

and associate of

the BMF, has appeared in the Jazz in June

lineup before, but this time his New York City-based tropical jazz

group, Tropique, will feature a slightly different lineup of players.

Hedman’s combo plays an engaging blend of warm-climate dance rhythms,

including salsa, Latin jazz, bomba and samba. A world-class conguero,

Hedman has a percussion style influenced by Cal Tjader and Armando Peraza.

The BMF is the chief sponsor of this concert.

New Englander Greg Abate returns to Lincoln with an all-star

group including pianist Phil DeGreg, bassist Harvie S. and drummer

Billy Hart. Except for the keyboard chair that James Williams usually

fills, it is the same band that accompanied the hard-edged saxophonist

on his most recent release, “Evolution.” An interview with Abate appears

on the cover.

Trumpeter Darryl White has developed a local and regional

reputation on trumpet and flugelhorn, both in performances and with two recordings,

the latest of which, “In the Fullness of Time,” was reviewed in the winter

2003 edition of Jazz.

White’s sextet will feature some of the best players

in the Midwest, including Denver pianist and Nebraska native Jeff

Jenkins, bassist Kenny Walker and drummer Matt Houston.

![Bobby Watson [Photo by Rich Hoover]](media/watson1.JPG) But the big news is the Kansas City sax “section” of Gerald

Dunn and Bobby

Watson. Watson’s addition to the program makes this a must-see.

The world-class alto saxophonist has appeared in Lincoln with his group

Horizon and as a guest soloist with the Nebraska Jazz Orchestra. But the big news is the Kansas City sax “section” of Gerald

Dunn and Bobby

Watson. Watson’s addition to the program makes this a must-see.

The world-class alto saxophonist has appeared in Lincoln with his group

Horizon and as a guest soloist with the Nebraska Jazz Orchestra.

At least in this neck of the woods, little was known of mandolin

player Don Stiernberg until his 2001 Blue Night release, “Unseasonably

Cool,” landed on the desk of Butch Berman, who gives it a rave review

in this edition of Jazz.

Though he plays an instrument usually associated with bluegrass

music, the Chicago-based Stiernberg and his sidemen (playing guitar,

bass and drums) prefer a repertoire consisting of such jazz standards

as “Where or When,” “Easy Living,” “Lover, Come Back to Me” and “I

Cover the Waterfront.”

top

|

Concert

Review

Jordan and Brown

keep the music alive

|

By Tom IneckSheila Jordan, 74 years young, proved herself a bold, ever-searching

improviser when she and bassist Cameron Brown took the stage

March 8 at Kimball Recital Hall in Lincoln. She also established an

immediate rapport with her listeners that lasted throughout the concert.

![Sheila Jordan & Cameron Brown [Photo by Rich Hoover]](media/jorbrow1.JPG) Her off-the-cuff vocal intro was a timely rap on the air-travel

blues, as she and Brown had just experienced them in their snow-delayed

sojourn from NYC to Lincoln, via Chicago. Most in the audience could

empathize with the unexpected hassles that can create fear and loathing

for frequent flyers. Her off-the-cuff vocal intro was a timely rap on the air-travel

blues, as she and Brown had just experienced them in their snow-delayed

sojourn from NYC to Lincoln, via Chicago. Most in the audience could

empathize with the unexpected hassles that can create fear and loathing

for frequent flyers.

Having made the connection that is essential for an intimate

artist-audience experience, Jordan launched into the Oscar Brown

Jr. classic “Hum Drum Blues.” By ending her phrases with rising notes,

she gave the otherwise depressing lyric a sense of uplift, hope and

optimism. In “Better Than Anything,” her joyful delivery convinced the

listener of her sincerity, especially when she improvised “better than

anything except singing in Lincoln.”

Brown, ever the sensitive accompanist, joined the scatting

Jordan in a voice-bass dialogue during “The Very Thought of You.”

The two master musicians have a rare compatibility, honed in the studio

on such recordings as “I’ve Grown Accustomed to the Bass” and allowed

full flight in live performance.

Jordan displayed an incredible range of material, moving deftly

from the evocative Scottish folk ballad “The Water is Wide” to Bobby

Timmons’ composition “Dat Dere,” with whimsical lyrics by Oscar Brown

Jr. and dedicated by Jordan to children and grandchildren. She handled

the tough time changes with ease.

Turning to her latest CD, she chanted the title track, a moving

Jordan creation called “Little Song,” which flowed naturally into a stunning

rendition of Lennon-McCartney’s “Blackbird” and back to the chant. The

story behind her composition—her Cherokee grandfather called her Little

Song—gave the tune a poignant and soulful depth.

Next, the duo pulled out the obscure “Real Time” by a Portland,

Ore., vibes player, then paid tribute to the immortal dance team of Astaire

and Rogers with “Freddie and Ginger,” a medley of dance tunes ranging

from “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” and “Cheek to Cheek” to “I Won’t

Dance,” and “I Could Have Danced All Night.” Jordan again exhibited

her refreshing optimism with a bright reading of “Pick Yourself Up (Dust

Yourself Off and Start All Over Again).”

Next, the duo pulled out the obscure “Real Time” by a Portland,

Ore., vibes player, then paid tribute to the immortal dance team of Astaire

and Rogers with “Freddie and Ginger,” a medley of dance tunes ranging

from “Let’s Face the Music and Dance” and “Cheek to Cheek” to “I Won’t

Dance,” and “I Could Have Danced All Night.” Jordan again exhibited

her refreshing optimism with a bright reading of “Pick Yourself Up (Dust

Yourself Off and Start All Over Again).”

Despite her basically sweet nature, Jordan is not without

some stinging criticism of our president, his aggressive foreign policy and

his reckless disregard for international opinion. After noting how embarrassing

it was to be an American on a recent European tour, she dedicated

a ballad rendition of “On a Slow Boat to China” to George Bush Jr.

Inextricably bound to Charlie “Bird” Parker and his bop legacy,

Jordan tackled the difficult “Confirmation,” a Parker tune with lyrics

by Leroy Mitchell. Brown launched the affair with a bass solo before

Jordan entered the fray, singing, swinging and soaring like the alto

horn of “Bird” himself. The mood was light, lilting and playful.

Jordan chose Mal Waldron’s lovely “You” as a memorial to the

late pianist. As Brown provided the bass background, the singer told

a dark Waldron joke about a man who had just returned from the doctor

under instructions to take pills for the rest of his life. The man expressed

some doubt over the prognosis, saying, “He only gave me seven pills.”

Their rendition of “Blues Skies” demonstrated Jordan and Brown’s

understanding of the importance of silence and well-chosen spaces

between phrases. Brown was especially imaginative as he provided bass

fills. Miles Davis was given his due with “All Blues,” “Freddie Freeloader”

and “Now’s the Time,” which included a scatted vocal recreation of

the Miles trumpet solo on a classic Parker recording.

“Art Deco,” with lyrics by Jordan, was the duo’s homage to

another late, great trumpeter, the under-appreciated Don Cherry.

As she moved through these loving tributes to fallen jazz artists,

Jordan showed an unmistakable emotional connection. With touching honesty,

she said that “keeping the music alive is all I’ve really ever wanted

to do.”

Jordan and Brown didn’t neglect the classics of the great

American songbook, faithfully interpreting “Honeysuckle Rose,” “Ain’t Misbehavin’,”

“Mood Indigo” and “I Got Rhythm,” as well as Thelonious Monk’s “Rhythm-a-ning,”

Charles Mingus’ tribute to Lester Young entitled “Goodbye Pork Pie

Hat,” and “Good Morning Heartache,” dedicated to Billie Holiday. Jordan

invited members of the audience to scat along with her bop rendition

of “Embraceable You,” which she dedicated to the film “Bird” and director

Clint Eastwood.

Completing the astoundingly varied concert were the voice-and-bass

masterpieces “I’ve Grown Accustomed to the Bass,” “Sheila’s Blues”

and Jordan’s own take on Michel Legrand’s “You Must Believe in Spring,”

as she added, “You must believe in love, in you, in jazz.”

Jordan’s evident passion for the music is infectious, and

makes believers of everyone within earshot.

top

|

Concert Review

Brubeck tells history of jazz piano at Folly

|

By Tom Ineck

KANSAS CITY, MO.-Dave Brubeck, at age 82, possesses all the

skill and

range of experience needed to embody the history of the jazz

piano, and in his March 8 quartet performance at The Folly Theater

he recited that history in elegant detail.

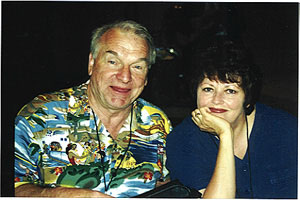

![Dave Brubeck & Tom Ineck [Photo by Bev Rehkop]](media/brubeck.JPG) The current Brubeck quartet, also featuring alto saxophonist

Bobby Militello, bassist Michael Moore and drummer Randy Jones, is

the best since the classic foursome that included Paul Desmond, Eugene

Wright and Joe Morello. Their compatibility allows each soloist complete

confidence in his compatriots and creates a level of sophistication

that never falters. Though considerably older than his sidemen, Brubeck

treats them as equals and never dominates. The current Brubeck quartet, also featuring alto saxophonist

Bobby Militello, bassist Michael Moore and drummer Randy Jones, is

the best since the classic foursome that included Paul Desmond, Eugene

Wright and Joe Morello. Their compatibility allows each soloist complete

confidence in his compatriots and creates a level of sophistication

that never falters. Though considerably older than his sidemen, Brubeck

treats them as equals and never dominates.

Brubeck and company began with “On the Sunny Side of the Street,”

the same tune that launches its current CD, “Park Avenue South,”

recorded live last summer at a Starbucks coffee shop in New York

City. Militello’s sax warmed quickly to the mid-tempo swing and sway

of the melody, doubling the time in short, boppish bursts.

Moore, best known for his tenure with pianist Bill Evans,

delivered a lyrical solo. Brubeck’s solo contained several chapters from

the history of the piano, including a two-fisted stride technique deftly

accelerating in tempo and venturing briefly into the realm of the avant garde.

“The Nearness of You” received a beautiful reading from Militello,

switching from alto sax to flute. Moore also offered a lovely arco

solo.

Brubeck, feeling comfortable in the recently restored grandeur

of the historic Folly Theater, told his audience that the quartet

would be trying out some new material with them. On what the leader

described as a traveling blues, Militello burst forth with a hot alto

solo, bending notes and traversing the scales with effortless skill.

Moore again followed with a bowed bass statement on the mid-tempo number.

From a symphonic suite written for (and recorded with) the

Cincinnati Symphony and director Erich Kunzel, the Brubeck quartet

introduced a fast waltz that included some marvelous alto sax-piano

trades. Brubeck proved his versatility by moving on to a Latin tune,

with some spicy flute work by Militello, followed by the master in a

remarkable piano solo that reached to the very heart of the music.

Militello was the focus in a powerful, free alto performance

on an unnamed piece, which segued into an exchange between the alto

and drums, then to an astounding drum solo by Jones. Brubeck was in

his element with a lighting quick rendition of the Gershwin warhorse

“I Got Rhythm,” again featuring Militello’s hard-blowing, inventive

improvisations.

Brubeck’s lovely dirge, “Elegy,” was a moving duo for piano

and bass. The piece was written for Randi Hultin, a Norwegian journalist

who recently died of cancer. Paying tribute to the music of New Orleans,

Brubeck introduced his composition “Crescent City Stomp,” with Mardi

gras-style march rhythm and a tour de force alto solo.

Perhaps the showcase piece of the evening was Brubeck’s lengthy

“Don’t Forget Me,” beginning with a tender classical piano introduction

and moving into a mid-tempo waltz featuring Militello with a lilting

sax statement. Moore followed with a breath-taking bass solo, taken

up by Brubeck with supreme elegance as his fingers skittered gently over

the keys in fugue style. The tune eventually returned to the ballad tempo

and a scintillating summation by the composer.

To a spontaneous roar from the audience, the quartet kicked

off the Desmond-penned Brubeck standard “Take Five. Militello, never

one to mimic his predecessor, deconstructed the well-worn melody, quoting

from other Brubeck compositions and, at one point, reproducing the

sound of a siren, as though to call in the fire units to bring his blazing

performance under control. Jones’ drum solo tastefully recreated and

rhapsodized on the familiar 5/4 time signature, superimposing his own

alternative rhythm patterns on the classic structure.

With good-natured humor, Brubeck announced the finale, “Show

Me the Way to Go Home,” which also closes the live CD. Militello

on alto, Moore on bass and Brubeck on piano contributed soulful solos,

anchored by the solid drumming of Jones, to send everyone home with

a warm feeling.

top

|

Concert

Review

Saxophonists pay tribute to Bird in hometown

|

By Tom Ineck

KANSAS CITY, Mo.-Organizers of the 5th Annual Charlie Parker

Memorial

Concert on March 22 in Kansas City could not have asked for a more

appropriate group of musicians to celebrate the occasion than the Frank

Morgan-Sonny Fortune Quintet.

Although the two alto saxophonists bring much different influences

to their playing styles, they decided to assemble and co-lead a quintet

in homage to the legendary bop innovator for a two-week tour in March.

The tour included dates in Oakland and Santa Cruz, Calif., and St.

Paul, Minn., before the stop in Kansas City. The quintet completed

its brief run with performances in Albuquerque, N.M., and Hollywood. Although the two alto saxophonists bring much different influences

to their playing styles, they decided to assemble and co-lead a quintet

in homage to the legendary bop innovator for a two-week tour in March.

The tour included dates in Oakland and Santa Cruz, Calif., and St.

Paul, Minn., before the stop in Kansas City. The quintet completed

its brief run with performances in Albuquerque, N.M., and Hollywood.

Even more apt was the KC venue, the Gem Theater Cultural &

Performing Arts Center at 1601 E. 18th St., a recently restored 500-seat

performance hall. Along with the nearby American Jazz Museum, Negro

Leagues Baseball Museum and The Blue Room jazz club, it has been instrumental

in the revival of the historic 18th and Vine Street area, which spawned

Kansas City jazz in the 1920s and 1930s but had fallen into disrepair

in recent times.

The 69-year-old Morgan is a light and lyrical player in the

classic Parker mold, and despite a stroke that left him partially

paralyzed a few years ago, he still can sustain a strong melodic line

through the chord changes. The younger Fortune, 64, draws his sound

from the beefier, bluesy sound of John Coltrane, a reputation he earned

during his tenure with pianist McCoy Tyner in the early 1970s. Like Coltrane,

he’s also a Philadelphia native. The contrasting styles of the two horn

men created an exciting study in dynamics.

Bolstering the performances of Morgan and Fortune were the

combined harmonic and rhythmic instincts of pianist George Cables,

bassist Henry Franklin and drummer Steve Johns. Cables, especially,

was more collaborator than accompanist.

Parker’s “Confirmation” opened the proceedings with flair.

Morgan and Fortune played a unison lead line before taking separate

solos, leaving plenty of space for solos by Cables and Franklin. The

bassist’s searching, experimental phrasing was closer to Fortune’s

style than Morgan’s.

Paying tribute to another influential saxophonist, Fortune dominated

Wayne Shorter’s “Footprints” with his brawny, hard-edged sound, circular

breathing and powerful Trane-like phrasing. Morgan’s solo, by comparison,

was constructed from short staccato bursts, rather than Fortune’s

long, flowing lines. As though following Morgan’s lead, Cables’ brilliant

solo was both melodic and percussive. Finally, Morgan and Fortune traded

four-bar breaks in a fantastic display of virtuosity.

Paying tribute to another influential saxophonist, Fortune dominated

Wayne Shorter’s “Footprints” with his brawny, hard-edged sound, circular

breathing and powerful Trane-like phrasing. Morgan’s solo, by comparison,

was constructed from short staccato bursts, rather than Fortune’s

long, flowing lines. As though following Morgan’s lead, Cables’ brilliant

solo was both melodic and percussive. Finally, Morgan and Fortune traded

four-bar breaks in a fantastic display of virtuosity.

Slowing the pace for a ballad medley, Fortune turned his attention

to the standard “What’s New?” He gave it a lush reading, comparatively

faithful to its familiar melody. Cables got the spotlight for his

rendition of “Body and Soul,” which he concluded with a beautiful

keyboard coda. For his ballad feature, Morgan chose Cables’ “Helen’s

Song,” with he performed with the composer, adding a soaring alto sax

solo.

The two saxophonists reunited for “A Night in Tunisia,” with

Morgan stating the melody and Fortune taking the first solo, a swirling,

exhilarating improvisational journey. Morgan took the lead-off solo

on “All Blues,” delving deeply into the modal changes. Fortune proved

the more powerful soloist, taking 10 choruses of sustained brilliance.

top

|

Concert Review

Tenor titans ignite hall with concert

sizzler

|

By Tom Ineck

In the grand tradition of the jazz tenor saxophone battles

of yore, tenor giants

Don Menza and Pete Christlieb went head-to-head March 25 as guest

soloists with the Nebraska Jazz Orchestra.

Menza and Christlieb, longtime friends and two of the most

popular studio musicians of the past 40 years, joined their horns

in immortal combat, raising the temperature level considerably for

the 400 listeners at The Cornhusker hotel ballroom. Menza and Christlieb, longtime friends and two of the most

popular studio musicians of the past 40 years, joined their horns

in immortal combat, raising the temperature level considerably for

the 400 listeners at The Cornhusker hotel ballroom.

Before the two guests took the stage, the NJO sax section

warmed up with a couple of tunes, including “Play It Again, Sammy,” a feature

for the saxophone section written for famed big-band composer-arranger Sammy

Nestico, and “Coastin’,” a mid-tempo swinger by Paul Baker that featured

brief, but effective statements by baritone saxophonist Scott Vicroy, trumpeter

Brad Obbink and bassist Andy Hall.

Menza and Christlieb hit the ground running with a brilliant,

blazing Menza arrangement of Ray Noble’s venerable flag-waver “Cherokee.”

After each of the tenor masters took a solo, they traded 4s, working

variations on the familiar theme from every angle and from the lower

registers to the upper range of their horns. Despite a sudden, offensive

electrical short in guitarist Pete Bouffard’s amp, the two kept focused

at breakneck speed.

“Nina Never Knew,” a ballad written for the Sauter-Finegan

band as a feature for trombonist Carl Fontana some 50 years ago,

featured Menza in his most romantic mood, playing a hard-edged tenor

in contrast with the light sound of clarinets, flutes and muted trombones.

From the extensive Menza songbook came “Groovin’ Hard,” an

irresistible, hard-charging tune first performed for a Munich radio

broadcast in the mid-1950s and later recorded by the Doc Severinsen,

Buddy Rich and Louis Bellson bands.

Christlieb’s solo was bluesy and imaginative, while Menza’s

began cautiously, building to a slow burn and finally igniting in

tenor pyrotechnics. Again the two brought the tune to a fiery climax

with extended trades. The Menza arrangement also featured the reed section

in a nice saxophone soli.

The orchestra began the second half of the concert with Menza’s

uptempo “Collage,” featuring fine solos by Darren Pettit on tenor

sax and Dave Sharp on alto sax. Rich Burrows struggled with miking

problems to deliver a tenor solo on Tom Kubis’ “Witchcraft.” Throughout

the evening, the sound-level inconsistencies of monitors, solo microphones

and the piano plagued the performance.

Menza and Christlieb rejoined the fray for Menza’s fast samba

called “Sambiana.” The two tenors stated the melody, took separate

solos, and then finished with traded passages as the band, driven

by drummer Greg Ahl, gathered momentum for the finale.

Christlieb took the spotlight for the Nestico arrangement

of Billy Strayhorn’s “Chelsea Bridge,” a recording that won the tenor player

a Grammy nomination earlier this year. His tone on the ballad standard

was big and breathy but had an angular attack that kept the listener’s

attention and prevented the performance from slipping into cliché.

Nothing could have followed the evening’s madcap capper, Menza’s

“Time Check,” an incredibly propulsive tune first waxed 30 years

ago by the Bellson band, in a recording featuring a younger Menza and

Christlieb. As Christlieb aptly noted before the duo dove into the

demonically difficult piece, “Playing this tune is like changing a

fan belt while the engine is running.”

It was an accurate description of the rhythmic tour de force,

which again had the tenor twosome taking hard-driving solos, including

a wry quote of “Summertime” by the comic Menza. A series of traded

horn statements followed, with Menza and Christlieb again acting like

a loving, long-married couple, finishing each other’s sentences in

a natural, flowing dialogue.

They finished with a dual cadenza that quoted “Blues Up and

Down,” the famous sax duet by Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt. It was

a fitting conclusion to this good-natured battle of tenor titans.

top

Concert

Review

Old enough to drive,

Djangirov puts pedal to metal

|

By Tom Ineck

Once a year, the Nebraska Jazz Orchestra parades its Young

Lions All-Star Big

Band for all to see and hear, but never has the NJO had a

young lion who roared so loudly as its guest soloist Jan. 22 at The

Cornhusker hotel ballroom in Lincoln.

Now old enough to drive, the 16-year-old Eldar Djangirov drove

circles around his contemporaries. The young piano wizard from the

Kansas City, Mo., area was making his return appearance as guest soloist

with the orchestra, and it was everything that the capacity audience

of nearly 600 could have imagined. Now old enough to drive, the 16-year-old Eldar Djangirov drove

circles around his contemporaries. The young piano wizard from the

Kansas City, Mo., area was making his return appearance as guest soloist

with the orchestra, and it was everything that the capacity audience

of nearly 600 could have imagined.

The Young Lions, 15 hand-picked musicians from high schools

in Lincoln and Omaha, started things off with four tunes. As always,

the young hopefuls were more confident and more successful in the ensemble

passages that they were in improvised solos. Standout soloists included

saxophonists Alex Levitov, John Guittar and Elizabeth Love, all of

whom also were in last year’s all-star group.

They did a nice job on “Stella by Starlight” and the Dizzy

Gillespie piece “Soul Sauce,” but it was a special treat when their

visiting colleague Djangirov took the daunting piano role on “88 Basie

Street.” He played that role tastefully, as if holding back slightly

in the company of lesser mortals.

The NJO began its set with “Skank 7,” a reggae-influenced

tune utilizing seven-count measures. Music director Ed Love played the tenor

sax intro, leading into a nice brass statement that segued into a Love solo,

followed by Tom Harvill on piano and the Hammond electronic keyboard. Chick

Corea’s “Sea Journey” featured wonderful harmonies in the brass and a hearty

solo by Rich Burrows on tenor sax.

Djangirov returned for a variety of settings. First, he raced

through Juan Tizol’s “Caravan,” combining technical virtuosity with

audacity and supreme confidence, echoing the keyboard pyrotechnics

of Oscar Peterson or even Art Tatum in his rolling left-hand figures

and his lightning-swift right hand.

With bassist Andy Hall and drummer Carlos Figueroa, Djangirov

expertly performed the Miles Davis blues “Freddie Freeloader” and

the ballad “You Don’t Know What Love Is.” He reached heights of astounding

speed and improvisational prowess on a solo rendition of Wayne Shorter’s

“Footprints.”

After this amazing display of Djangirov’s keyboard accomplishment,

the members of the NJO meekly returned to the stage, but immediately

proved themselves equal to the task with the uptempo workout “Pressure

Cooker.” Djangirov stayed out of the spotlight for much of this tune

and the next one, “Thelonious Assault,” a reinterpretation of Thelonious

Monk’s “Well You Needn’t.”

It was the finale that proved most impressive. Gershwin’s

“I Got Rhythm” has been done in many different styles, but none like this

Rob McConnell arrangement with the brass section setting the furious pace

and Djangirov exploding into an incredible solo.

His standing ovation was richly deserved.

top

Concert Review

Gulizia helps NJO remember

Sinatra, Basie |

By Tom Ineck

The Nebraska Jazz Orchestra’s decision to salute Count Basie

and Frank

Sinatra in the season finale may not seem an obvious choice,

but the two legends of American popular song had much in common.

Sinatra and Basie made two studio recordings together and

collaborated on the classic “Sinatra at the Sands” live performance

in 1966. They swaggered with equal confidence and had a natural rapport,

much like the teaming May 6 at The Cornhusker hotel. Sinatra and Basie made two studio recordings together and

collaborated on the classic “Sinatra at the Sands” live performance

in 1966. They swaggered with equal confidence and had a natural rapport,

much like the teaming May 6 at The Cornhusker hotel.

Guest vocalist Tony Gulizia, an Omaha native now living in

Vail, Colo., has a longtime association with several members of the

NJO, including music director Ed Love. Gulizia also has that Sinatra

panache, that charismatic hipster charm. As a friend observed, he has

that “nouveau Rat Pack thing.”

Following a snippet of the Basie theme song, “One O’Clock

Jump,” the NJO began the concert in earnest with the Basie-style riffing

of “Count Bubba” by Gordon Goodwin, warming up each horn section separately.

The long piece also included individual solos by trumpeter Bob Krueger,

trombonist Pete Madsen, guitarist Peter Bouffard and Love on alto sax.

Trombonist Tommy van den Berg, a senior at Lincoln Southeast

High School and this year’s Young Jazz Artist, was featured in an

opening set. Van den Berg handled the changes nicely on the mid-tempo

Dave Sharp arrangement of “Then End of a Love Affair,” but really excelled

on Sonny Rollins’ rollicking “St. Thomas,” with a small combo consisting

of piano, guitar, bass, drums and percussion. Tom Harvill’s lively

piano solo captured the irrepressible joy of the calypso rhythm. Van

den Berg also sounded confident on the minor-key blues shuffle “A Switch

in Time,” written by Sammy Nestico for the Basie band.

Gulizia began with “Teach Me Tonight,” displaying his sure

sense of vocal dynamics and a personal way of phrasing the lyrics.

In “The Lady is a Tramp,” he cleverly mimicked Ol’ Blue Eyes with casual

lyric changes, substituting “girls” with “broads.”

From the Stan Kenton songbook came the Bill Holman tune “Cubajazz,”

as though specially chosen for the evening’s extra percussion players,

including Gulizia’s younger brother, Joey, on bongos and surprise guest

Doug Hinrichs on congas.

A wonderful musician who is also adept on the piano and organ

keyboards, singer Tony Gulizia showed an impeccable sense of timing

on “Fly Me to the Moon.” As if to remind Gulizia of his more modest and

more ethnic musical roots, Love brought out an accordion, on which Gulizia

good-naturedly played “The Chicken Polka,” to the delight of orchestra

members and the audience of 400.

Back to business, Gulizia switched to Gershwin, singing a

Dave Sharp arrangement of “Summertime” in samba time. Brother Joey

added congas and Jeff Patton soared on a spirited trumpet solo. Moving

to the piano, Gulizia led a quartet featuring guitarist Peter Bouffard,

bassist Andy Hall and percussionist Joey Gulizia for one of the highlights

of the evening, a lovely rendition of Dori Caymmi’s “Like a Lover,” best

known as a Sergio Mendes hit in the late 1960s.

The quartet continued with “In the Wee Small Hours of the

Morning,” with Gulizia diving immediately into the lyric with little

introduction. He showed his two-fisted, driving piano style on the

fast-paced “I Love Being Here with You.”

A Quincy Jones arrangement of “I’ve Got You Under My Skin”

completed the regular concert program, but Gulizia returned for a

well-received encore on “Every Day (I Have the Blues),” in the style

of Basie and singer Joe Williams.top

Concert Review

McNeil quartet gives seamless

performance

|

By Tom Ineck

No one could ever accuse the John McNeil Quartet of playing

clichés.

With few comments from the leader regarding the title or

the inspiration behind each tune, the band’s two-hour performance

Jan. 31 at Kimball Recital Hall in Lincoln flowed seamlessly, as though

creating a symphonic suite or simply an extended conversation among

four confidants. But none of the melodies, chord changes or improvised

solos could be described as predictable.

McNeil is a trumpeter, composer and band leader worthy of

far more recognition than he has acquired in his 54 years. While leading

a quartet since 1979, and the current lineup since 1997, McNeil has

developed a rare rapport with his sidemen: guitarist Andrew Green, bassist

Tom Hubbard and drummer Ron Vincent, who last performed in Lincoln as timekeeper

for baritone saxophone legend Gerry Mulligan in the early 1990s.

The midtempo opener seemed to come out of left field, with

a brief statement of the melody followed by a subtle, searching guitar

solo alternating chords and single-note runs. McNeil’s trumpet solo

soared freely while staying narrowly and imaginatively within the chord

changes.

An uptempo stop-time piece metamorphosed into another tune,

with Green’s jagged, hard-edged guitar solo demanding attention. His

tasteful use of effects (assorted slides, volume pedal, finger-tapping

and hammer-on techniques among them) never got in the way and always

added color to the overall sound.

The same can be said of Hubbard’s warm tone and perfect intonation,

whether plucking or bowing the bass, and of Vincent’s bag of tricks,

which included tambourine, chimes, mallets and other percussion paraphernalia.

Exhibiting a well-paced sense of dynamics, the quartet moved

gracefully through a ballad, featuring a guitar solo of restrained

virtuosity. After Green and the rhythm section had created an exotic

Eastern mood, McNeil entered with an extraordinary solo, as though adding

his own comments to the conversation.

Using a large shot glass as a slide on the strings, Green

created an eerie effect, playing a quavering unison line with McNeil

on trumpet.

The one recognizable melody all night was “Nothing Like You,”

an obscure tune written by singer Bob Dorough for an otherwise instrumental

Miles Davis recording session. McNeil gave it an aptly quirky reading.

In an intriguing departure from the jazz norm, the quartet

performed McNeil’s composition “Urban Legend,” a tune whose rather

conventional folk-rock sentiment contrasted dramatically with McNeil’s

“outside” trumpet statements.

With “Blue Boat,” McNeil and company demonstrated their affinity

for the blues, albeit a very odd sort of blues progression. It is

unlikely that anyone in the audience of 300 could have hummed along

with these fast and furious changes.

top

Friends of Jazz

Bob Popek is a musician's best friend

|

By Tom Ineck

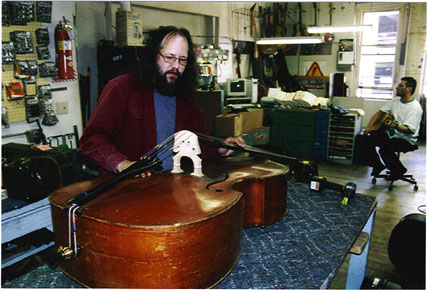

On most days, you can find Bob Popek hunkered down in the back

room of the

third floor at Dietze Music House in downtown Lincoln, surrounded

by the well-worn tools of his essential trade. He’s a string musician’s

best friend.

For more than 25 years, Popek has been an instrument repairman,

capable of returning life and harmony to the most dejected and abused

of guitars, banjos, fiddles, mandolins, basses. Generations of rock,

folk, bluegrass, jazz and classical string players have Popek to thank. For more than 25 years, Popek has been an instrument repairman,

capable of returning life and harmony to the most dejected and abused

of guitars, banjos, fiddles, mandolins, basses. Generations of rock,

folk, bluegrass, jazz and classical string players have Popek to thank.

“What I realized, very early on, is that people are very attached

to their instruments, and they want them to play the way they want them

to play,” Popek said. “And, no two people play alike.”

He began by specializing in instrument adjustments and custom

guitar setups, the basic configuration of the instrument’s strings and

fretboard. Then, he added a one-year warranty on all of his work.

“That was totally unheard of back then, because an instrument’s

made out of wood and it shifts. But, I needed to make a statement when

I started. I was pretty gung-ho.” Popek quickly became known as the “setup

king,” which earned him many longtime friends among local string benders

and fret meisters.

One of his current projects is restoring a double bass, vintage

circa 1890, which

once belonged to his mentor, the late bassist and string repairman

Mark Pierce, who was in his 90s when he died in the mid-1970s, after

running the Dietze repair shop for many years. In storage for 30 years,

the bass was only recently purchased by the store for restoration. One of his current projects is restoring a double bass, vintage

circa 1890, which

once belonged to his mentor, the late bassist and string repairman

Mark Pierce, who was in his 90s when he died in the mid-1970s, after

running the Dietze repair shop for many years. In storage for 30 years,

the bass was only recently purchased by the store for restoration.

“When I found out it was Mark Pierce’s, with the connections,

I thought it was too important to let that go on and lose the history

it had, that I had to buy it and restore it and use it for a better cause,”

Popek said.

When brought back to playing condition in Popek’s skilled hands,

the bass will be made available for visiting bassists who have to

leave their instruments at home, an increasingly common situation

when air travel is a dicey proposition. Already the carved instrument,

which will be valued at $5,000 when finished, is scheduled for play

during three of this year’s Jazz in June concerts in Lincoln.

Popek began his association with Dietze as a guitar teacher

in 1976. Within six months, he was helping out in sales and landed a

part-time job with Pierce in the repair shop, in addition to teaching.

Pierce was doing orchestral string repair—basses, cellos, violas and violins.

“Mark Pierce taught me the practical side of repair, realistically

what you saw in life,” Popek said. “A lot of things aren’t pretty.

When somebody falls with a bass—no two people fall alike.”

Pierce, however, didn’t have time to teach his young apprentice

everything. Pierce, however, didn’t have time to teach his young apprentice

everything.

“I worked with him for about a year, until we realized that

Mark wasn’t going to be around much longer.” Dietze sent Popek to a repair

school in Minnesota for a year of formal training that would groom him

to replace Pierce, who died while Popek was away. Because Popek was the

first student sponsored by a music store, he was treated with special care,

to raise the school’s placement rate and to set an example for other stores.

When he returned to Lincoln, he was ready.

“We had enough work back then for it to be a good, solid part-time

job, and it took maybe four or five years to build up to where I couldn’t

keep up, and we slowly started to hire, to evolve.” The repair operation

now includes Popek, two fulltime assistants in downtown Lincoln, one

fulltime repairman at the south Lincoln store and one at the Omaha location.

He credits local bassist and UNL Associate Professor Rusty

White with helping him to broaden his skills into other areas, such

as perfecting setups for string basses, building his own adjustable

bridges and designing his own C-string extensions.“More than 20 years

ago, when he first came to town, he came into the shop and said, ‘Bob,

I’ve seen your work and you do OK, but you’re going to do better,’” Popek

recalled. “I told him, ‘Tell me what you expect, and I’ll try to meet it,’

so he was a very heavy influence on me.”

The first music store in Lincoln to offer full service on all

instruments sold, Dietze can handle anything that comes through the

door, from acoustic string instruments to brass, from drums to electric

keyboards and amplifiers. With the closing of other Lincoln area music

stores and Dietze’s solid regional reputation, business continues to grow.

“We’re doing work with the Omaha Symphony. I do work, on a

regular basis, as far west as Grand Island. I have regular customers

as far away as Denver, Kansas City and Minnesota. We’ve diversified

quite a bit. We’re not a shop to limit ourselves to certain things.

It’s not a surprise to walk up into the shop and see a grand piano standing

in what might be our last available place to stand because somebody wanted

a piano refinished. We won’t turn anything down.”

Just the string family alone is a prolific one, including mandolin,

guitar, banjo, steel guitar, bass, violin, viola and cello, not to mention

such second and third cousins as the ukulele, zither and dulcimer.

“You can think of a thousand differences in each instrument,

but there are just as many similarities,” Popek noted. “They all require

the same mechanism to tighten the string. They all require a string,

a sound box and a neck to perform on.”

Popek also works with manufacturers to create improvements

in instruments and accessories. For example, he helped to solve a design

problem on a string bender that could bend one or two strings independently.

He also devised a display model guitar that allows customers to test different

pickups before they make a purchase.

What truly tests the repairman’s knowledge and skill is restoring

a vintage instrument to its former glory.

“With restoration, you want to try to keep with the theme that

the instrument was built in, in its time. A lot of lost knowledge

you need at your fingertips to do a job correctly.” In recent years,

the Internet has become an invaluable tool for Popek in his search

to access the history of instruments and the knowledge of instrument

repairmen worldwide.

top

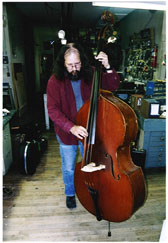

Berman guitar gets tender

loving care

|

By Tom Ineck

Like most dedicated musicians, Butch Berman’s relationship

with his instruments

is close. He’s especially close to his 1961 Fender Esquire, and

when it comes to repairs and

maintenance of this classic axe, he turns it over to Bob Popek at

Dietze Music House (Popek is featured in a Friends of Jazz article

above).

Berman recently related the story of his guitar and the man

who keeps it humming. It began in the mid-1970s. Berman recently related the story of his guitar and the man

who keeps it humming. It began in the mid-1970s.

“When the Megatones broke up, we were looking for a guitar

player. We tried a bunch of different things, and nothing really clicked.”

Berman, a piano player with the Megatones, also played occasional

guitar, so he offered his services.

“It worked, but I didn’t have a guitar. At the time, Charlie

had this really cool guitar, so he sold me his ’61 Fender Esquire.

It’s a great guitar. So, I started using this guitar a lot. Like a sports

car, it needs maintenance. I’d always been hanging around Dietze, and

somehow I met Popek.”

Berman told Popek he was having problems with guitar, and took

the instrument to Dietze’s third-floor repair shop. The skilled craftsman

saw the guitar’s value and potential. He also understood exactly how

Berman wanted it to play and sound. Popek has been the instrument’s

“caregiver” ever since.

“Over the years, probably about every season, I take my guitars

into him and he strums it and checks it out, changes the strings and

repairs it. I used to have a problem with breaking strings and tuning,

and now I hardly ever break a string or go out of tune. He’s been the

man for all my stringed instruments ever since that day. He really has

an understanding. He’s a real talented guy.”

top

Tomfoolery

Thompson applies

tourniquet to the soul

|

By Tom Ineck

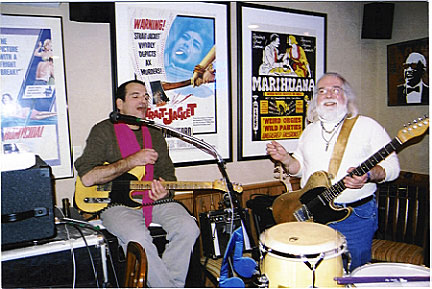

HASTINGS, Neb.—English trad-rock apothecary Richard Thompson

arrived

April 23 at Hastings College carrying an old kit bag of tricks

filled to the brim.

As promised in the subtitle of his new CD, “The Old Kit Bag,”

the concert of largely new material contained “unguents, fig leaves

and tourniquets for the soul.” On the rare occasion of a Thompson electric

band tour of America’s heartland, the quartet’s inspired performance for

some 650 people at French Memorial Chapel did, indeed, have welcomed healing

powers. As promised in the subtitle of his new CD, “The Old Kit Bag,”

the concert of largely new material contained “unguents, fig leaves

and tourniquets for the soul.” On the rare occasion of a Thompson electric

band tour of America’s heartland, the quartet’s inspired performance for

some 650 people at French Memorial Chapel did, indeed, have welcomed healing

powers.

The band was one of the best I’ve seen since my first encounter

with Thompson in 1985 at Parody Hall in Kansas City, on the heels of

the “Across a Crowded Room” release. The common denominator of both concerts

was bassist Rauri McFarlane, then making his first U.S. visit, but now

a seasoned veteran on both electric and upright bass. Multi-instrumentalist

and harmony singer Pete Zorn, a long-time Thompson road warrior, and Earl

Harvin, an outstanding percussionist from Dallas, gave the foursome a

tight, self-contained sound, like a well-oiled machine.

“The Old Kit Bag” seems, at once, more accessible melodically

and more complex lyrically than many of his recent releases. As a composer,

Thompson has never avoided the tough subjects of life, love, faith and

death, but his new writing is especially pointed. A devout Sufi Muslim,

he has undoubtedly been affected by the world’s sordid events of the

recent past.

Unexpectedly, Thompson immediately launched into the rocker

“Tear-Stained Letter,” a classic flag-waver that usually is held in

reserve for later in the show. He followed with several tunes from the

new CD, beginning with “Gethsemane,” a meditation on the meaning of life

concluding with the question: “Who sucked out the freedom, days without

end? Under the weight of it all you must bend.”

The rocker “Pearly Jim” was followed by “Outside of the Inside,”

a scalding attack on the self-righteousness of the religious right.

It begins, “God never listened to Charlie Parker. Charlie Parker lived

in vain. Blasphemer, womanizer, let a needle numb his brain. Wash away

his monkey music. Damn his demons, damn his pain.” McFarlane’s booming

acoustic bass contrasted dramatically with Harvin’s sharp rat-a-tat-tat

on the bongos.

From the past came “Razor Dance” and the heart-wrenching “Missie

How You Let Me Down,” featuring Zorn on alto flute. Zorn switched

to soprano sax for a heavenly rendition of “Al Bowlly’s in Heaven,”

with Thompson on acoustic guitar and Harvin displaying his subtle but

effective brush technique.

Returning to his new material, Thompson played a solo acoustic

guitar version of “A Love You Can’t Survive.” As if to flaunt his versatility,

he then performed (in Italian) his rocking arrangement of “So Ben Mi

Ca Bon Tempo,” written circa 1600 by Orazio Vecchi. By the way, the U.S.

release of “Kit Bag” contains a limited-edition bonus disc containing

an acoustic live version of this tune, Prince’s “Kiss,” and a video clip

from a BBC documentary on Thompson.

“One Door Opens” had the feel of a traditional dance number,

with acoustic guitar, mandolin, acoustic bass and bongos setting the

mood. After the rocking “I’ll Tag Along,” Thompson again dipped into

his considerable back catalog for “Bank Vault in Heaven,” “I Want to

See the Bright Lights Tonight” and “Shoot out the Lights.”

“She Said It Was Destiny” was another finger-snapping melody

from “Kit Bag.” A very fast rendition of the favorite “Two Left Feet”

was followed by the evening’s only extended jam, on the breath-taking

finale “You Can’t Win.”

The crowd brought the boys back for two encores, beginning

with a solo acoustic “1952 Vincent Black Lightning,” “Wall of Death”

and “Crawl Back (Under My Stone).” For the second encore, they brought

out “Man In Need” and finished with two new tunes, “Jealous Words” and

“Word Unspoken, Sight Unseen.”

Ever the professional, Thompson and the band played a generous

23 tunes, including 10 from the new release (counting the Italian novelty).

Thompson fans, a famously obsessed clan of followers, have

kindred spirit Turner McGehee and the Hastings College Artist Lecture

Series to thank for making possible this free concert appearance.

top

Concert Review

Jerry Seinfeld improvises like jazz saxist

|

By Butch Berman

DES MOINES, Iowa-Jerry Seinfeld—jazz? Yeah, why not? Improvisation

is the

ability (I know, Jamey Abersold sez everyone can improvise,

but you know what I mean) to alter the original arranged piece of material,

whether it be musical or spoken word. Well, I tell ya—after witnessing

Jerry Seinfeld’s new stand-up concert Jan. 21 at the Des Moines, Iowa,

Civic Center’s sold-out second show, I could easily draw the comparison.

Dig this. The parallels between a sax player’s own personal

take on whatever composition he is blowing—and keeping (sometimes, ever

so slightly) the intended tune intact and Jerry’s shtick shows that he

obviously has a game plan. There were several times I second-guessed what

current hot topic he would put his spin on next, yet his relaxed, but slightly

smug demeanor, almost took me back to the old Jack Benny days. His timing,

like a veteran musician, was and is and probably will always be flawless. Dig this. The parallels between a sax player’s own personal

take on whatever composition he is blowing—and keeping (sometimes, ever

so slightly) the intended tune intact and Jerry’s shtick shows that he

obviously has a game plan. There were several times I second-guessed what

current hot topic he would put his spin on next, yet his relaxed, but slightly

smug demeanor, almost took me back to the old Jack Benny days. His timing,

like a veteran musician, was and is and probably will always be flawless.

After his opening act (I can’t remember his name, but he was

a pretty damned good standupper who really got the pro-Jerry audience

primed) the lights dimmed as Jerry creeped on the bare stage, except

for his lone barstool, glass of water and mike to one of the most heartfelt

standing Os before he even opened his mouth I’ve ever seen. It gave me

a rush I’ll always remember.

Obviously, everyone in the audience, including myself, lived

and breathed for Jerry, as well as his daily reruns. His only faux

pas, which I’ve experienced at the two previous shows I’ve seen him perform

at, was his attempt to use the audience in a question-and-answer session

for his encore. It might work in a super-hip venue like L.A. or New York,

but the people he picked out of the Lincoln, Omaha and Des Moines audiences

proved to be fairly mundane. Yet, he takes his chances with that, and

the trouper he is makes it sorta work.

With “The Sopranos” and “Sex in the City” in their last season,

please come back, Jerry! You’re the best… the best, Jerry!

top

DVD Review

Funk Brothers story makes life-shaking DVD

|

By Butch Berman

If you’re lucky, and live long enough, a few major incidents

will probably take

place to shake and/or shape our lives.

Looking back, I recall being home on furlough from Wentworth

Military Academy (WMA) at the ripe age of 16 and seeing Dylan in ’65.

His first set was solo, followed by (at the time) the loudest, in-your-face

backup band I’ve ever heard. Looking back, I recall being home on furlough from Wentworth

Military Academy (WMA) at the ripe age of 16 and seeing Dylan in ’65.

His first set was solo, followed by (at the time) the loudest, in-your-face

backup band I’ve ever heard.

Next, also while at WMA in 1968, I snuck out, ingested my first

LSD and saw Jimi Hendrix live in Kansas City. Lastly, catching Gerry

Mulligan, months before his untimely death, inspired me to embrace jazz

as never before, and to co-found the Berman Music Foundation with my then-partner,

Susan Berlowitz. These are three standouts that first came to mind.

Yesterday…I had another. A full-page ad in Entertainment Weekly

sent me on a search to Barnes and Noble. A nervous, near frantic hunt

finally proved fruitful. VOILA! I’m now holding the new DVD entitled,

“Standing In the Shadows of Motown,” inspired by author and educator Alan

Slutskey and director Paul Justman. This is the story of the self-penned

Funk Brothers, who from 1959 to the early 70’s provided the back-up and

rhythm sections for Berry Gordy and Motown Records. The Funk Brothers

did make a fairly decent living, but were certainly not overpaid and were

left fairly obscure and unheralded. Motown made a fortune from these incredible

musicians, turning dozens of talented singer/songwriters into stars, and

recording hundreds of hits. Hey, I had every 45 from this era, and outside

of bassist James Jamerson, I hadn’t known the names of any of these cats.

So please, from now on remember these names: Drummers William

“Papa Zita” Benjamin, Richard “Pistol” Allen and Uriel Jones; bassists

James “Igor” Jamerson and Bob Babbit; guitarists Robert White, Eddie “Chank”

Willis and Joe Messina; pianists Joe Hunter, Earl: Chunk of Funk” Van

Dyke and Johnny Griffith; percussionist Eddie “Bongo” Brown and vibe-player/tambourine

specialist Jack “Black Jack” Ashford, they comprise the heart and soul

brotherhood of funk.

While researching a book on the Motown bass phenom James Jamerson…a

visit to his widow turned author Slutsman’s project into a 15-year odyssey

to finish this film while these men were still healthy enough to appreciate

their long over due adulation. Sadly, six of these gentlemen have

since passed, but this work of art is God sent. Truly a spiritual experience,

as countless educational gifts lie within this two DVD set. Almost life-changing,

the packaging is as well done as I’ve ever seen, and I’ve seen a lot.

Grab it, open your hearts, dance the night away and rejoice.

The Funk Brothers are back again…encased forever in a box set worth

building a shrine for.

top

Colorado correspondent enjoys Rocky Mountain Hi (Fi)

|

By Dan Demuth

Ed Polcer brought “The Magic of Swing Street” to Colorado Springs

on Feb.

19, musically recreating the period from the early ‘30s to

the late ‘40s of New York’s famed 52nd Street—a street that Arnold

Shaw titled his book as “The Street that Never Slept.”

Accompanying cornetist Polcer was Alan Vache on clarinet, Dan

Barrett on trombone, bassist Frank Tate, John Cocuzzi handling the piano

and vices and Joe Ascione on drums. My notes will concentrate more on

the event rather than the ritualistic listing of the songs played and

comments on each. Reminiscent of a club-size atmosphere, an appreciative

crowd of just under 200 people comfortably filled this venue at the Red

Lion hotel. Accompanying cornetist Polcer was Alan Vache on clarinet, Dan

Barrett on trombone, bassist Frank Tate, John Cocuzzi handling the piano

and vices and Joe Ascione on drums. My notes will concentrate more on

the event rather than the ritualistic listing of the songs played and

comments on each. Reminiscent of a club-size atmosphere, an appreciative

crowd of just under 200 people comfortably filled this venue at the Red

Lion hotel.

Ed Polcer has the too oft-unseen ability to create a comfortable

mood, as if one were conversing with him in your living room. It was

obvious the musicians were also comfortable in this mode, it reflects

in their playing and the mood resonates with the audience. The selections

were what one could have heard on The Street, perhaps mistakenly too often

put into a back as “traditional” by those who don’t care to really venture

outside of their cozy but limited sphere. As Shaw notes, Basie, Hawkins,

Gillespie, Goodman, Herman, Parker, Vaughan, Tatum, Garner, Holiday, (Artie)

Shaw, Norvo and Shearing were but a very few of the habitués of

the 30-odd establishments nestled in an area of less than two blocks on

The Street. If that’s traditional, I’ll have some. I would prefer to categorize

this jazz as timeless.

To name just a few of the performance highlights: Vache’s beautiful

solo performance of “Danny Boy;” Barrett displaying his skill on the

88s; Polcer’s intuitive comments; the “just right” touch on all numbers

by Ascione and Tate; and Cocuzzi playing “intermission” piano, doing bluesy

vocals on “I Want a Little Girl” and “Hello Central, Give me Dr. Jazz.”

A conversation with Polcer validated my thought that Harry “The Hipster”

Gibson was perhaps the epitome of the many intermission pianists who earned

their bread on 52nd Street.

All of the musicians lingered afterwards to talk with anyone

who wanted to, another nice touch. This event was sponsored by the

Pike’s Peak Jazz & Swing Society. While on tour, two weeks prior to coming to the Springs,

Polcer’s group stopped in a studio in Durham, N.C., and recorded an

11-track CD—“Let’s Hit It!”—in one day, no rehearsals, no kiddin’.

It’s great.

top

Editor’s Note: At your request,

we will mail a printed version of the newsletter. The online newsletter

also is available at this website in pdf format for printing. Just click

here: Newsletter

|

![Norman Hedman [Photo by Rich Hoover]](media/hedman1.jpg) Percussionist Norman Hedman, a longtime friend, consultant

and associate of

the BMF, has appeared in the Jazz in June

lineup before, but this time his New York City-based tropical jazz

group, Tropique, will feature a slightly different lineup of players.

Hedman’s combo plays an engaging blend of warm-climate dance rhythms,

including salsa, Latin jazz, bomba and samba. A world-class conguero,

Hedman has a percussion style influenced by Cal Tjader and Armando Peraza.

The BMF is the chief sponsor of this concert.

Percussionist Norman Hedman, a longtime friend, consultant

and associate of

the BMF, has appeared in the Jazz in June

lineup before, but this time his New York City-based tropical jazz

group, Tropique, will feature a slightly different lineup of players.

Hedman’s combo plays an engaging blend of warm-climate dance rhythms,

including salsa, Latin jazz, bomba and samba. A world-class conguero,

Hedman has a percussion style influenced by Cal Tjader and Armando Peraza.

The BMF is the chief sponsor of this concert. Sinatra and Basie made two studio recordings together and

collaborated on the classic “Sinatra at the Sands” live performance

in 1966. They swaggered with equal confidence and had a natural rapport,

much like the teaming May 6 at The Cornhusker hotel.

Sinatra and Basie made two studio recordings together and

collaborated on the classic “Sinatra at the Sands” live performance

in 1966. They swaggered with equal confidence and had a natural rapport,

much like the teaming May 6 at The Cornhusker hotel. One of his current projects is restoring a double bass, vintage

circa 1890, which

once belonged to his mentor, the late bassist and string repairman

Mark Pierce, who was in his 90s when he died in the mid-1970s, after

running the Dietze repair shop for many years. In storage for 30 years,

the bass was only recently purchased by the store for restoration.

One of his current projects is restoring a double bass, vintage

circa 1890, which

once belonged to his mentor, the late bassist and string repairman

Mark Pierce, who was in his 90s when he died in the mid-1970s, after

running the Dietze repair shop for many years. In storage for 30 years,

the bass was only recently purchased by the store for restoration. Dig this. The parallels between a sax player’s own personal

take on whatever composition he is blowing—and keeping (sometimes, ever

so slightly) the intended tune intact and Jerry’s shtick shows that he

obviously has a game plan. There were several times I second-guessed what

current hot topic he would put his spin on next, yet his relaxed, but slightly

smug demeanor, almost took me back to the old Jack Benny days. His timing,

like a veteran musician, was and is and probably will always be flawless.

Dig this. The parallels between a sax player’s own personal

take on whatever composition he is blowing—and keeping (sometimes, ever

so slightly) the intended tune intact and Jerry’s shtick shows that he

obviously has a game plan. There were several times I second-guessed what

current hot topic he would put his spin on next, yet his relaxed, but slightly

smug demeanor, almost took me back to the old Jack Benny days. His timing,

like a veteran musician, was and is and probably will always be flawless. Looking back, I recall being home on furlough from Wentworth

Military Academy (WMA) at the ripe age of 16 and seeing Dylan in ’65.

His first set was solo, followed by (at the time) the loudest, in-your-face

backup band I’ve ever heard.

Looking back, I recall being home on furlough from Wentworth

Military Academy (WMA) at the ripe age of 16 and seeing Dylan in ’65.

His first set was solo, followed by (at the time) the loudest, in-your-face

backup band I’ve ever heard.