|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

January 2004 By Tom Ineck Ted Eschliman frequently and casually refers to himself as a

“hack.” In the Eschliman is just being modest. A talented multi-instrumentalist,

singer, composer and arranger with a degree in music education from

the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, he is part owner and marketing

director of Dietze Music House, where he’s been employed for more

than 23 years. Most recently his far-ranging interest in music has made him a

devotee of the jazz mandolin, as a player and collector of

mandolins, as well as a dogged promoter of the instruments and the

people who play them. He was largely responsible for bringing the

Don Stiernberg Quartet to Lincoln for last summer’s Jazz in June

concert series, and in 2003 he started his own website to preach the

gospel of jazz mandolin: www.jazzmando.com. He now sits on the Jazz

in June board of directors and was instrumental in adding guitarist

John Carlini (with guest artist Stiernberg) to the 2004 lineup. “I picked up the mandolin about 5½ years ago,” Eschliman recalls.

“It was an intriguing instrument and different from guitar. What

surprised me was how little was known about what this instrument

could do. As I got into it, I discovered that there is a really rich

tradition. My 96-year-old grandmother talked about the mandolin

clubs at the University of Nebraska back in the teens, almost a

hundred years ago.” With the advent of the banjo, the electric guitar, and swing

bands, the mandolin literally began to recede into the background of

popular music because its more delicate, high-register sound could

not be heard. There were few innovators outside the Smoky Mountains,

where mandolins still were figured prominently in bluegrass bands,

especially those of Bill Monroe and the Stanley Brothers. He says he was so enchanted by “the perfect symmetry and jazz

potential” of his first mandolin in 1998 that he became “very

passionate about bringing this genre to the front. People are

familiar with jazz guitar, with Joe Pass and Pat Metheny and George

Benson. I’m a little bit of a hack guitar player, but I’ve

discovered in picking up the mandolin that there’s a whole world out

there that has yet to be developed.” It is unfortunate, says Eschliman, the small, four-stringed

instrument has gotten itself a bad rap, as it is usually associated

with “toothless codgers sitting on the back porch in bib overalls.”

The stereotypical mandolin players are either hillbillies or

schmaltzy Italian troubadours, limiting the instrument’s appeal for

a larger audience. Unlike the structural freedom of jazz, tunes traditionally

associated with the fiddle and mandolin are constricted to a

diatonic scale that is very limiting for more adventurous players.

But to Eschliman’s educated ears, the mandolin seems ideal for jazz. “The acoustics of the instrument lends itself so well to the

genre that I’m amazed it hasn’t been tapped into sooner by more

people.” By nature, jazz broadens the palette from which the

mandolin artist can work. “Jazz gets you into not only a richer harmonic vocabulary; it

also pulls in multiple keys. If you listen to a good, jazzy Broadway

show tune, you’re going to have eight or nine different tonal

centers there, so harmonically it’s a lot more engaging. To some

bluegrass players, it’s frightening.” Eschliman is quick to point

out exceptions to this rule, virtuosos who have blended their

bluegrass roots with jazz dabbling, most notably Jethro Burns and

David Grisman. Eschliman and his wife have a five-year-old daughter, and he has

nothing but praise for his wife’s patience and understanding. “She’s gotten used to the fact that she never knows what I’m

going to be doing and what I’m going to get deeply into and

passionate about. Lately, it’s been this whole jazz mandolin thing.

It’s been my ticket to the world.” Eschliman launched the website as a way to journal the things he

was learning about his new instrument. He began transcribing

exercises from the keyboard to the mandolin fret board to share with

others online, first in music notation, then in tablature. Through his website, Eschliman corresponds with mandolin

students, musicians and fellow “hacks” from around the globe,

including Belgium, Australia, New Zealand and France. Jazz mandolin,

it seems, is growing in popularity and awareness, especially in

Europe, he said. Searching the Web a couple of years ago, he came up with Don

Stiernberg, the Chicago-based jazz mandolinist whose quartet

performed in Lincoln last June. “Coincidently, I had gone to a mandolin festival in Lawrence,

Kansas, 2½ years ago, and he was doing a clinic there. I got to meet

him there, and we got to be pretty good friends. Our dream is that

our kids will think of the mandolin as just as much a jazz

instrument as a trombone or a sax. That’s a pretty tall dream.” Part of that dream may be realized soon. The popular Mel Bay

Publishing company has asked Eschliman to write a book on jazz

mandolin. He already has written a couple of instructional articles

for mandolinsessions.com, another way of expanding interest in the

instrument. “That’s just such virgin territory right now that a hack like me

can come up with stuff like that. It’s funny that I could be an

expert when there are people who are more qualified. The thing I’ve

known in being involved in the arts is that there are plenty of

professional players that are just monster virtuosos and

technicians, but they couldn’t tell you anything about what they’re

doing. They couldn’t explain it.” Eschliman’s own collection of mandolins includes an Ovation for

plugged-in acoustic playing; a blue, custom-made Rigel; a

traditional Gibson for bluegrass playing; an Epiphone that used to

belong to bluegrass legend Jethro Burns; and a miniature gypsy-style

Djangolin. The market for mandolins and acoustic string music in general has

grown, perhaps due to the phenomenal success of the recent film “Oh

Brother, Where art Thou?” Eschliman thinks it also may be a reaction

to the deluge of electric guitars and guitar players in pop music. To help counter the emphasis on guitars and other more

traditional jazz instruments, Eschliman currently is touting jazz

mandolinists Michael Lampert and Will Patton; and similarly flavored

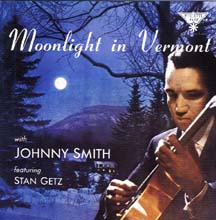

French gypsy jazz. By Dan Demuth COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. — Master guitarist Johnny Smith was kind Perhaps most people remember him from the “Moonlight in Vermont”

recording of 1952 on Roost which garnered Downbeat’s “Jazz Record of

the Year” award and led to a meteoric rise to fame, but this was not

an overnight happening. A little background is in order at this

point.

“Sitting in” with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Symphony

Orchestra and Dimitri Mitropoulis and the New York Philharmonic.

Studio work with the NBC Symphony Orchestra under Arturo Toscanini,

who he describes as a tyrannical genius, and for network shows

including Sullivan, Godfrey, Garroway and Fireside Theater. Nightly

gigs on 52nd Street with virtually every musician of note. For the interview I had some prepared questions, but also had

brought along some of his recordings for points of discussion, the

liner notes providing somewhat of a retrospective look at his

career. Dan Demuth: Artie Shaw’s career somewhat paralleled yours

in that he was working ‘round the clock, studio work in the daytime,

gigs every night and then he eventually walked away from it all. How

did you survive these types of schedules, was it youth, the

adrenalin, both? Johnny Smith: (Chuckling) I don’t know. One of my favorite

things I have mentioned, I was playing an engagement in Birdland,

and I also was doing a thing with the New York Philharmonic under

Mitropoulis. I finished Birdland at 4 a.m. and at 9 o’clock that

morning I was sitting in the middle of the Philharmonic Orchestra.

At the time I left New York I was doing studio, television,

recording, night clubs. I was working around the clock. DD: The reason for leaving all of this—perhaps a

combination of the grueling schedules and a personal situation? JS: It was a tragic situation. My wife died. Our daughter

was four years old. No way could I take care of her, working around

the clock. I would have to hire nursemaids. I had family here in

Colorado Springs, so I figured that was the best excuse I would ever

have to get the hell out of New York. DD: Why Colorado Springs? JS: I had been out here once. I had two brothers who were

out here, and they had moved our parents out here from New York

City. I came out to see my father for the last time, who had

terminal cancer. It was within a month or so back in New York that

my wife died. DD: Over the years you had recorded and toured with the

likes of Kenton, Goodman and Basie. The Basie tour makes me ask,

where was Freddie Green? Was he away at that time? JS: No, No. I tell people that Freddie Green was with

Count Basie longer than Count Basie. Freddie Green was strictly a

rhythm guitar player, I was a soloist. He was there on the tour. He

was one of my very favorite people. DD: I had mentioned Artie Shaw earlier. Did you ever

record with Shaw? DD: Was he as irascible as everyone said? He has always

seemed to have a penchant for saying what was on his mind. JS: Well I only knew him on a personal basis. It’s when

you work with somebody that the truth comes out, but I never worked

with Artie. DD: I have brought along some of my collection of your

recordings to help me with the notes. (Producing the Royal Roost 78

“Moonlight in Vermont”) Am I correct, is this your first recording?

JS: Yes, this is the original one. “Tabu” is on the other

side.

DD: The story goes that you felt “Tabu” might be the side

that had a chance to succeed? JS: Yes, it was kind of an uptempo flashy type of thing.

And what happened was “Moonlight in Vermont” was really kind of a

fluke. The jazz disc jockeys started using it as a background while

they talked, and that’s how that caught on. DD: The group with you on that recording—Stan Getz, Eddie

Safranski, Don Lamond and Sanford Gold. I admit I am not all that

familiar with Gold. Not being a musician, I have always been

interested in how a group comes together for a recording. JS: Back in the ‘40s, for the radio shows, I formed a

little trio. I had heard about Sanford, and I was able to get NBC to

hire him as a piano player for my trio. This went on for several

years, and the contractor who was hiring the musicians, Dr. Roy

Shields, formed this big orchestra for a weekly radio show. He asked

me to form a small group within the orchestra, and to write weekly

arrangements to perform during the show. I met Stan Getz at a party.

He knew I was with NBC and expressed a desire to get off the road

and get some studio work. I was able to get NBC to hire him and I

formed this quintet. Don Lamond, Eddie Safranski and Sanford Gold

were all on staff. Sanford had a friend, Teddy Reig, who owned Roost

Records and gave him an air check tape. Teddy said, “Heck, we’ll do

a couple of tunes,” and that’s how that original thing happened. DD: Amazing! (Producing Roost 10" LP “Johnny Smith

Quintet”) I believe this is your first LP? JS: That’s correct. As a result of the success of

“Moonlight in Vermont,” we recorded other things which they put

together for this LP. DD: Two of these, “Tabu” and “Jaguar,” are credited to

you. Were these some of your first efforts which you wanted on this

LP? JS: Well, prior to that I did arranging for Benny Goodman

and other people. Knowing this, the record labels would always try

to get the artist to come up with some originals so they wouldn’t

have to pay copyright fees. As a matter of fact, “Jaguar” was a song

I wrote that we performed with the small group within the big

orchestra I mentioned earlier. DD: (Producing the Roost 10" LP, “In A Sentimental Mood,”

with a shaded green cover, obviously a photo of Johnnie, guitar in

lap, hands over his face as in a funk). Would you say this photo is

of a pensive, perhaps moody guitarist? I think he looks familiar! JS: Gosh, I don’t even remember this. Maybe I was hiding

my face in shame! DD: I doubt that. My question is regarding the amount of

input you had as an artist as to what went on the cover of the LPs,

as they offered so much more physical space than modern CDs. JS: Virtually none. I did on one of the string albums. I

had a photographer take a picture of some of the score I was doing . DD: This LP has “Walk Don’t Run” on it. It must have been

quite a thrill when some years later the Ventures had a huge hit

with it. JS: Well, Chet Atkins had recorded it. The Ventures

covered his recording, which then became the big hit. I really had

very little to do with it. I didn’t even name the song. I just

called it “Opus,” and the record company owner came up with “Walk

Don’t Run”. DD: (Producing the Roost LP “Easy Listening”). OK, on this

cover there is a photo of a guitarist and a very attractive young

lady reclining in front of a fireplace, but I don’t think that

gentleman is you. JS: No, no, sorry it isn’t! DD: (Producing the Roost LP “Designed for You,” which

features four guitars superimposed over each other to form a clover

effect). The Guild brand is very prominent on the guitars. Is this

just happenstance? JS: I had designed a guitar for Guild. I think they just

borrowed one of them and used it for the cover design. DD: (Producing the Forum LP “Jeri Southern meets Johnny

Smith”). Perhaps of interest to Nebraska newsletter readers as Jeri

is from Royal, Neb. Have you done other recordings with Jeri? How

does a session such as this come about? JS: No, this was the only one. I had worked on the same

bill before with Jeri at Birdland on quite a few occasions. When

this LP was done, she was not at her peak—bless her heart, her voice

was kind of gone—and they asked me if I would do the arrangements,

which is kind of a hidden thought, because they knew I would do

them, and wouldn’t charge them. And if you notice, it’s never

mentioned, “Arrangements by Johnny Smith.” DD: (Producing a copy of Decca recording “Jazz Studio”).

There is a guitarist listed on here as Sir John Gasser, someone I

think you know very well. Can you tell me the story behind this

recording? JS: Stan Getz had gone back on the road, and to satisfy

recording requests we were to add Paul Quinichette. Paul didn’t want

Decca (a competing label) to use my name, so I was listed as Sir

Jonathan Gasser, a terrible thing! DD: Mosaic recently issued an eight-CD set limited edition

containing 178 of your Roost sessions. Are you able to share in the

royalties on this? JS: Unfortunately no. I did most of the arranging on all

of those sessions, but if you don’t have a song copyrighted to you,

there is nothing to collect. DD: Your peers have all been very complimentary of your

playing through the years. Did you have any guitarists that you

particularly enjoyed? JS: Oh gosh yes. Starting before WWII, I practically

worshiped Django Reinhardt, Charlie Christian, and of course Les

Paul. I was so heavily involved in studio work that afterwards I

would go around listening to such fine players like Chuck Wayne,

Jimmy Raney. I keenly appreciated all of these good players. DD: Several years back you and Chet Atkins played together

at a Dick Gibson Jazz Party, at the Paramount in Denver. Attendees

have told me it was great, that you two appeared as if you had

played together forever. JS: We were very dear friends, all through the years. I

went down to Nashville on a couple of occasions to record things for

Chet. (One with) Don Gibson. I did some arranging for other people.

We were very close friends.

DD: I have several Atkins and Gibson LPs. Anything in

particular I could seek out that you arranged? JS: One thing in particular I did with Don Gibson, called

“Gibson, Guitars & Girls.” I don’t think I even have it. DD: I will check mine to see if I have it. (I did, and

have given Johnny a tape). Is there any definitive book or

discography on your life and recordings? JS: No, I have had several people want to do this, but I

tell them they’re wasting their time. I’ve never been busted for pot

or arrested or anything, so my biography would be very dull reading.

There have been quite a few things put out regarding a discography,

but not a biography. DD: Have you kept copies of all your recordings? JS: My wife kind of keeps the recordings in tow. I think

with all of the reissues I probably do. I really don’t keep track of

it. DD: Have you ever looked back and thought to yourself, if

you hadn’t quit the business, what might have been? JS: No. I tell everybody—which is really true—I have got

to be one of the most fortunate people in the world because

everything that I ever dreamed of doing, really wanted to do, well

all those dreams came true. Fortunately, making huge amounts of

money wasn’t one of them. Now I’m at peace with everything. I’ve

often felt sorry for the people who were on the way out saying,

“Gee, I wish I would have done this or that.” I’m not one of them. After the interview, Johnny invited me into his “room” for a

libation. We continued discussing things (not taped). He has a

modest amount of memorabilia on the walls, fully retaining what

really counts, the memories in his mind. Photos of Rosie Clooney and

her sons flying in here to get mountain flying lessons from Johnny

(his failed Air Corps ambition later realized by being a long time

private pilot and teacher). He spoke of his great love of fishing—he

and friends go twice a year deep sea fishing off of Mexico. He

toured several times with Bing Crosby, relating how on the last

tour’s end he bid Bing goodbye in England on a Monday, and Bing died

on the golf course in Spain four days later. All interviews must end somewhere, but I did not feel as if I had

been part of an interview. It was more of a conversation with an old

friend I had never met before.

By Tom Ineck A longtime member of

Norman Hedman’s Tropique and a friend of the Furnace last appeared in Lincoln with Hedman’s tropical jazz

ensemble for a BMF-sponsored Jazz in June performance last summer.

His accomplishments, however, went far beyond his tenure with Hedman. Furnace was a multi-reedist, composer and arranger and had

performed with Jaki Byard, Art Blakey, Abdullah Ibrahim, McCoy

Tyner, Randy Weston, Al Hibbler, Tito Puente, Machito, Charlie

Persip, Chico O’Farrill and Bernard Purdie. He can be heard on

recordings with Mongo Santamaria, Milt Hinton, Craig Harris, Johnny

Copeland, Elliot Sharp, The Julius Hemphill Saxophone Sextet, The

New York Jazz Composer Orchestra, the Jazz Passengers, and Wayne

Gorbea, as well as Tropique. One of his longtime associations was as alto and baritone

saxophonist with the Brooklyn Sax Quartet, which also included Fred

Ho (baritone and alto sax), David Bindman (tenor sax), and Chris

Jonas (soprano sax). The quartet’s debut recording is “The Way Of

the Saxophone” (Innova, 2000). Bindman and Ho formed the group in 1995, associating the project

with the members’ home base, the borough of Brooklyn. With a fiery and sharp sound, Furnace, came out of the r&b camp

of Johnny “Clyde” Copeland’s “Texas Twister” and the Cuban

bandleader Mongo Santamaria in the ’80s. In the ’90s he worked

extensively with Julius Hemphill; including in the all-sax Julius

Hemphill Sextet, which teamed him with Marty Ehrlich, Andrew White,

James Carter, Fred Ho, and (in Hemphill’s absence) Tim Berne. Furnace played alto sax and flute on five tracks from Tropique’s

release of 2000, “Taken By Surprise.”

Feature Articles

October 2003

May 2003

January 2003

Articles 2002

Feature Articles

Profiles, music news, memorials

broadest sense, the word is short for “hackney” and usually refers

to someone who does something in a banal, routine or commercial

manner.

broadest sense, the word is short for “hackney” and usually refers

to someone who does something in a banal, routine or commercial

manner.

Colorado Correspondent

Guitarist Smith tells of an illustrious career

![Johnny Smith [File Photo]](media/104smith2.jpg) enough to grant me an interview at his home on Jan. 25. He has lived

in Colorado Springs since leaving New York in the late 1950s, a move

dictated by the loss of his wife, his determination to raise their

four-year-old daughter in a better environment, and a growing

distaste for the requirements to remain a headliner in the music

scene. A difficult decision for someone of his stature at that time?

In an interview in the Colorado Springs Independent he was quoted as

saying, “The greatest view I ever had of New York City was when I

emerged from the Lincoln Tunnel on the New Jersey side and watched

the Manhattan skyline recede in my rearview mirror.”

enough to grant me an interview at his home on Jan. 25. He has lived

in Colorado Springs since leaving New York in the late 1950s, a move

dictated by the loss of his wife, his determination to raise their

four-year-old daughter in a better environment, and a growing

distaste for the requirements to remain a headliner in the music

scene. A difficult decision for someone of his stature at that time?

In an interview in the Colorado Springs Independent he was quoted as

saying, “The greatest view I ever had of New York City was when I

emerged from the Lincoln Tunnel on the New Jersey side and watched

the Manhattan skyline recede in my rearview mirror.” His

first “professional” gigs were as a teen in a self descriptive band,

Uncle Lem and His Mountain Boys. Into the Army as WWII escalated, he

aspired to be a pilot in the Air Corps but failed on a vision test.

He was assigned to a band unit whose patriotism-inspired chart

requirements did not include a guitarist but rather a need for a

trumpeter. With no prior experience but a ton of due diligence, he

mastered the trumpet and later was assigned to a unit that allowed

him to play his first love, jazz. Returning to Vermont after the

war, his job as a staff musician at a local NBC affiliate offered

the chance of getting a demo tape auditioned at NBC headquarters in

New York. The door had been opened.

His

first “professional” gigs were as a teen in a self descriptive band,

Uncle Lem and His Mountain Boys. Into the Army as WWII escalated, he

aspired to be a pilot in the Air Corps but failed on a vision test.

He was assigned to a band unit whose patriotism-inspired chart

requirements did not include a guitarist but rather a need for a

trumpeter. With no prior experience but a ton of due diligence, he

mastered the trumpet and later was assigned to a unit that allowed

him to play his first love, jazz. Returning to Vermont after the

war, his job as a staff musician at a local NBC affiliate offered

the chance of getting a demo tape auditioned at NBC headquarters in

New York. The door had been opened.

JS: No, I never did. I was too busy. He had formed a group called

the Gramercy Five. I never worked with them, as I was too busy doing

studios and everything else. If I remember correctly, he used Tal

Farlow. But, I knew Artie. We used to hang out after hours.

Memorial

Tropique saxophonist Sam

Furnace dies

Berman Music Foundation, saxophonist Sam Furnace died

recently of liver cancer at age 48.

Berman Music Foundation, saxophonist Sam Furnace died

recently of liver cancer at age 48.

Editor’s Note:

At your request, we will mail a printed version

of the newsletter. The online newsletter also is available at this

website in pdf format for printing. Just click here: Newsletter