|

New Orleans Jazz Fest feature

story

BMF receptions for Jazz in June

Photo Gallery

Benny Powell Memorial

NJO, Lied Center and Brownville schedules

Charles Mingus and

the Racial Mountain

Tomfoolery

|

July 2010

Feature Articles

Music news, interviews, memorials, opinion |

|

Feature Story

New Orleans continues

to offer the best

in musical heritage,

food and decadent fun

By Tom Ineck

NEW

ORLEANS—After 15 years, I returned to the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage

Festival with mixed emotions and more than a little trepidation. After

all, the city and I had changed considerably since 1995.

![French Quarter streetscape features historic wrought-iron architecture and neon-lit bars. [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/710NOJFQuarter.jpg) Nearly

five years ago, Hurricane Katrina and subsequent flooding inundated 80

percent of the city and rendered whole neighborhoods uninhabitable. The

Big Easy lost many of its residents to other parts of the country,

including the musicians who made New Orleans so unique. Some may never

return. The total urban population shrunk from a pre-Katrina high of

450,000 to less than half that before rebounding to an estimated

350,000. Now, the citizens who remain must deal with a growing oil spill

wreaking havoc with the Gulf of Mexico’s ecological system and

endangering the vital fishing and tourism industries. Nearly

five years ago, Hurricane Katrina and subsequent flooding inundated 80

percent of the city and rendered whole neighborhoods uninhabitable. The

Big Easy lost many of its residents to other parts of the country,

including the musicians who made New Orleans so unique. Some may never

return. The total urban population shrunk from a pre-Katrina high of

450,000 to less than half that before rebounding to an estimated

350,000. Now, the citizens who remain must deal with a growing oil spill

wreaking havoc with the Gulf of Mexico’s ecological system and

endangering the vital fishing and tourism industries.

Since I

last attended Jazz Fest, I have grown older, slower and less patient

with large outdoor crowds. I have less energy to fight my way to the

front of the stage, and my knees are too weak to stand for hours in the

heat and humidity. In short, I’m too old for Woodstock revisited. But my

desire for good music—of all kinds—remains strong. Fortunately, the

festival still gives the open-minded,

![Antoine's Restaurant is one of New Orleans' oldest eatiing establishments. [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/710NOJFAntoine.jpg) eclectic

music fan a dozen stages to choose from, and the music sounds just as

good while seated under a tent as it does standing in an open field. If

you balance the two experiences, you can enjoy both and not suffer early

burn out. eclectic

music fan a dozen stages to choose from, and the music sounds just as

good while seated under a tent as it does standing in an open field. If

you balance the two experiences, you can enjoy both and not suffer early

burn out.

Separate

stages devoted to different styles of music are positioned throughout

the 145-acre site, the infield of the mid-city Fair Grounds Race Course.

Some artists are gathered under the festival’s broad stylistic umbrella

for their star power alone, but most are linked in some way to the

Crescent City’s unique musical heritage.

For

example, the 41st annual festival (April 23-May 2) featured

Celtic soul icon Van Morrison, jam rockers Widespread Panic, folk

veterans Simon & Garfunkel, grunge rock favorites Pearl Jam, the

ubiquitous British chameleon Elvis Costello, comic Steve Martin doing

his bluegrass thing, and fusion guitar god Jeff Beck. Among the no-shows

was Aretha Franklin, who was replaced by Earth, Wind and Fire. These are

the celebrated names that ensure that Jazz Fest will remain solvent as

it continues to attract hundreds of thousands of people from around the

world.

![People line up for traditional New Orleans cuisine. [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/710NOJFFood.jpg) For

the $45 daily admission, the most fanatical of fans scurry from stage to

stage to catch the big acts from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. each of seven days

spread over two weekends, often standing for hours and settling for a

glimpse of their favorite stars on the huge video screens set up at the

two largest outdoor venues. Those of us seeking a more intimate

relationship with the music historically connected to New Orleans seek

refuge in the smaller tents, where we can sit and enjoy the sounds of

traditional jazz, progressive jazz, blues, funk, soul, or gospel.

Smaller outdoor stages offer Cajun and zydeco music and the spectacle of

Mardi Gras Indians dancing in their beaded and feathered finery and

parading through the grounds. For

the $45 daily admission, the most fanatical of fans scurry from stage to

stage to catch the big acts from 11 a.m. to 7 p.m. each of seven days

spread over two weekends, often standing for hours and settling for a

glimpse of their favorite stars on the huge video screens set up at the

two largest outdoor venues. Those of us seeking a more intimate

relationship with the music historically connected to New Orleans seek

refuge in the smaller tents, where we can sit and enjoy the sounds of

traditional jazz, progressive jazz, blues, funk, soul, or gospel.

Smaller outdoor stages offer Cajun and zydeco music and the spectacle of

Mardi Gras Indians dancing in their beaded and feathered finery and

parading through the grounds.

These are

the traditions on which the city’s cultural reputation is based, and

they continue to resonate. Whether the artists are the Neville Brothers,

Ellis

![My cousin Jerry Siefken (left) is among the second-liners in the Economy Hall tent. [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/710NOJFJerry2.jpg) Marsalis,

C.J. Chenier, the Dirty Dozen, BeauSoleil and Allen Toussaint, or

lesser-known practitioners of the art, they represent a phenomenon more

than a century in the making. Marsalis,

C.J. Chenier, the Dirty Dozen, BeauSoleil and Allen Toussaint, or

lesser-known practitioners of the art, they represent a phenomenon more

than a century in the making.

So it was

with much anticipation and a little anxiety that my wife, Mary Jane

Gruba, and I returned to Jazz Fest after a 15-year absence. We arrived

in New Orleans April 28 equipped with tickets for the four-day second

weekend, a little cash for the rows of vendors offering authentic Cajun,

Creole and international cuisine, light clothing with some reliable

walking shoes and hats and plenty of sunscreen. My cousin Jerry Siefken,

a local resident and

![Singer Dee Dee Bridgewater is interviewed at Music Heritage Stage. [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/710NOJFDeeDee1.jpg) Jazz

Fest veteran, loaned us a couple of compact folding chairs, which we

never used. Typically, the weather varied from warm and sunny the first

day to comfortably cloudy the second and third days and persistently

rainy the final day. Jazz

Fest veteran, loaned us a couple of compact folding chairs, which we

never used. Typically, the weather varied from warm and sunny the first

day to comfortably cloudy the second and third days and persistently

rainy the final day.

With a

detailed, gridded music schedule, we planned our days in advance, but

prepared for last-minute changes—the best way to enjoy a relatively

stress-free Jazz Fest experience. For example, on Thursday we took in

the distinctly New Orleans funk sounds of Kirk Joseph’s Backyard Groove

and Ivan Neville’s Dumpstaphunk, then retired to the indoor Music

Heritage Stage for an interview with singer Dee Dee Bridgewater before

fighting the swarming crowds to enjoy a hilarious performance by Steve

Martin, sitting in on banjo with bluegrass virtuosi the Steep Canyon

Rangers. We ended the day at the WWOZ Jazz Tent for Bridgewater’s

stunning celebration of Billie Holiday.

![The crowd waits for Jeff Beck to take the stage. [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/710NOJFBeck9.jpg) Among

other memorable moments that weekend were sets by pianist-composer Allen

Toussaint’s Jazzity Project, Delfeayo Marsalis and the Uptown Jazz

Orchestra, Brian Blade and the Fellowship Band, Astral Project, the New

Leviathan Oriental Foxtrot Orchestra, Ellis Marsalis, and Steve Riley &

the Mamou Playboys. During a rainy Sunday morning, moving performances

by several soulful choirs provided a much-needed respite under the

gospel tent. And, after 40 years of hero worship I realized a dream by

witnessing Jeff Beck in all his six-stringed glory. Some of these

performances are reviewed in more detail elsewhere on the BMF website

and in the BMF newsletter. Among

other memorable moments that weekend were sets by pianist-composer Allen

Toussaint’s Jazzity Project, Delfeayo Marsalis and the Uptown Jazz

Orchestra, Brian Blade and the Fellowship Band, Astral Project, the New

Leviathan Oriental Foxtrot Orchestra, Ellis Marsalis, and Steve Riley &

the Mamou Playboys. During a rainy Sunday morning, moving performances

by several soulful choirs provided a much-needed respite under the

gospel tent. And, after 40 years of hero worship I realized a dream by

witnessing Jeff Beck in all his six-stringed glory. Some of these

performances are reviewed in more detail elsewhere on the BMF website

and in the BMF newsletter.

![St. Louis Cathedral in Jackson Square [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/710NOJFCathedral.jpg) The

precious hours before and after Jazz Fest should always be spent

sampling a few of New Orleans other highlights, especially those in the

pedestrian-friendly French Quarter. Stroll through Jackson Square to see

St. Louis Cathedral in the morning sunlight before stopping for café au

lait and beignets (doughnut-like pastries smothered in powdered sugar)

at Café du Monde, also a good place for celebrity sightings. On the day

we visited, actress Maggie Gyllenhaal and her three-year-old daughter

were there. The

precious hours before and after Jazz Fest should always be spent

sampling a few of New Orleans other highlights, especially those in the

pedestrian-friendly French Quarter. Stroll through Jackson Square to see

St. Louis Cathedral in the morning sunlight before stopping for café au

lait and beignets (doughnut-like pastries smothered in powdered sugar)

at Café du Monde, also a good place for celebrity sightings. On the day

we visited, actress Maggie Gyllenhaal and her three-year-old daughter

were there.

For an

early lunch, we recommend the deli at Central Grocery, home of the

classic muffuletta sandwich, a large helping of Italian meats and

cheeses dressed with a special olive salad inside a round loaf of

focaccia

![Mary Jane Gruba enjoys a beignet and cafe au lait at Cafe du Monde. [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/710NOJFDuMondeMJ.jpg) bread.

A leisurely stroll through the Quarter offers a combination of

old-country streetscapes, quaint shops, beautiful wrought-iron

architecture, eccentric street musicians and pressurized water trucks

removing the dregs of the night before. bread.

A leisurely stroll through the Quarter offers a combination of

old-country streetscapes, quaint shops, beautiful wrought-iron

architecture, eccentric street musicians and pressurized water trucks

removing the dregs of the night before.

Evenings

should include dinner at one of the many fine restaurants in or near the

Quarter. During our stay, we had excellent meals at Tujague’s, the Bon

Ton Café and the Palace Café. Expect to spend $80 to $150 for two,

depending on the quality and quantity of the wine. For a special treat,

visit one of the city’s night spots for a music experience much more

relaxed than a day at Jazz Fest. This year, we returned to one of our

favorite haunts, the Snug Harbor jazz club, for a Saturday evening

performance by New Orleans jazz pianist Henry Butler, fronting a stellar

![The Bon Ton Cafe in the Central Business District [Photo by Tom Ineck]](media/710NOJFBonTon.jpg) quartet.

Among the regular performers at Snug Harbor are R&B singer Charmaine

Neville, Marsalis patriarch Ellis and Astral Project. Based on previous

visits, we also recommend Tipitina’s and the Rock ‘n’ Bowl. quartet.

Among the regular performers at Snug Harbor are R&B singer Charmaine

Neville, Marsalis patriarch Ellis and Astral Project. Based on previous

visits, we also recommend Tipitina’s and the Rock ‘n’ Bowl.

Jazz Fest’s

popularity makes careful planning essential. Consider booking a hotel or

bed-and-breakfast room six months in advance. Expect to pay at least

$200 a night for a decent room in the Quarter. Stay just outside the

Quarter, spend less and still get around on foot, rented bicycle,

streetcar or other public transportation. Don’t rent a car!

For the

2011 edition, some music artists will be announced later this year or

early next year, but detailed schedules are not available until about a

month before the festival begins. Some 4,000 musicians perform each year

during Jazz Fest.

top |

|

BMF

Receptions

BMF celebrates another Jazz in June

series |

|

By Grace

Sankey-Berman

LINCOLN,

Neb.—I had the pleasure of hosting the Berman Music Foundation board

members in a reception at our office after our annual meeting June 15.

In the

![BMF colleagues meet June 15 at Lazlo's [Photo by Laura Hansen]](media/710Receptions1.jpg) past our meetings had been scheduled in the winter, which

sometime presented travel challenges for board members that came from

out of town. Also, we thought it would be fun for those members to

experience the great Lincoln tradition that is Jazz in June. past our meetings had been scheduled in the winter, which

sometime presented travel challenges for board members that came from

out of town. Also, we thought it would be fun for those members to

experience the great Lincoln tradition that is Jazz in June.

After the

meeting we all went to the Sheldon Sculpture Garden where Kansas City

songstress Angela Hagenbach was to perform. It turned out to be a

beautiful evening for great jazz. Angela and her band, along with one of

my favorite pianists, Roger Wilder, serenaded us with familiar and

always pleasing standards like “Summertime,” and she also featured some

songs from her own recordings. It was the perfect way to relax after a

busy day.

Then we

headed to the BMF office for a reception. It was nice to catch up with

Dan Demuth, who despite storm, snow or sleet unfailingly makes it to the

annual board meeting from his home in Colorado. I always look forward to

spending time with Wade Wright of San Francisco, who is the

longest-serving board member. We have the best conversations on just

about any subject. Russ Dantzler came for the meeting from New York City,

despite his very busy

![Catherine Sinclair and Kay Davis [Photo by Grace Sankey-Berman]](media/710Receptions3.jpg) summer schedule. I can’t wait to make it back to

the city because he is the best host. Even though bassist Gerald Spaits

had a gig that same night in Kansas City, he made the 3½-hour drive to

Lincoln for the meeting and drove back right after. summer schedule. I can’t wait to make it back to

the city because he is the best host. Even though bassist Gerald Spaits

had a gig that same night in Kansas City, he made the 3½-hour drive to

Lincoln for the meeting and drove back right after.

We are

lucky and grateful to be working with such great friends, especially Kay

Davis. She worked with Butch for many years and even though she has

retired to

Arkansas, she continues to make the annual trip back to Lincoln for the board meeting. Kay was kind enough to spend a few days

with me while she was here. Our time together is always fun and goes by

too fast. Kay is recovering from a bout with pneumonia and we wish her a

speedy recovery.

BMF was

happy to host two more receptions during this year’s Jazz in June

series. Jeff Newell and his New-Trad Octet were great fun to hang out

with after their June 22 concert, and guitarist Jerry Hahn graciously

joined us after a great performance June 29, the final concert of the

season. Thanks go to Martha Florence, Laurie J. Sipple and all the Jazz

in June volunteers who were able to join us. I would like to extend my

appreciation to Ruthann Nahorny for always being there, and to Laura

Hansen. Thanks for all your help.

top |

|

Photo Gallery

BMF friends gather to visit at BMF

offices |

|

|

|

Grace Sankey-Berman, Tony Rager and Martha Florence |

Brian Muhlbach, Laurie Sipple and Tom Ineck |

|

|

|

|

Friends include Jim and Kay Wunderlich, Russ Dantzler,

Cynthia Taylor and Greg Harm |

Ed and Loretta Love |

|

|

|

Grace Sankey-Berman, Jimmy Akpan and Adrienne

Pettigrew |

Brad Krieger and Cathy Patterson |

|

|

|

|

Mary Jane Gruba, Jane and Peter Reinkordt

and Tom Ineck |

Wade Wright and Ruthann Nahorny |

|

|

Memorial

Benny Powell's passing reunites trio of

friends |

|

By Tom Ineck

LINCOLN, Neb.—As Berman Music

Foundation consultant Russ Dantzler

noted, a trio of BMF friends who also

were frequent collaborators were

reunited with the June 26 death of

trombonist Benny Powell at age 80.

Preceding Powell were bassist Earl May

in January 2008 (also at 80), then Jane

Jarvis in January of this year at age

94.

![Butch Berman and Benny Powell in 1999 [File Photo]](media/710ButchPowell.jpg) The

three shared the stage here on Oct. 8,

1999, at the Cornhusker Hotel, a

fundraiser for the Lincoln Seniors

Foundation that was partially funded by

the BMF. “Lifelong Living and All That

Jazz” was the theme that night, and it

proved to be a valid philosophy for

Powell, Jarvis, and May. The trio at

that time had already lived a combined

225 years, and much of that time was

spent performing the music they loved. The

three shared the stage here on Oct. 8,

1999, at the Cornhusker Hotel, a

fundraiser for the Lincoln Seniors

Foundation that was partially funded by

the BMF. “Lifelong Living and All That

Jazz” was the theme that night, and it

proved to be a valid philosophy for

Powell, Jarvis, and May. The trio at

that time had already lived a combined

225 years, and much of that time was

spent performing the music they loved.

When the trio received a standing

ovation before playing the first note,

Powell quipped, “We chose the right time

to become older persons.” As I later

wrote, the performance “joyfully

illustrated that creativity need not be

stifled by longevity. Indeed, it offered

ample evidence that the creative arts

can help prolong a youthful approach to

life.”

The trombonist was also a fine vocalist

of great sensitivity. That night in

1999, he sang the Jarvis composition

“I'll Make it This Time,” a tune the

pianist wrote for a Broadway production.

Later in the evening, Powell used his

trombone to state the melody of the

Jarvis-penned tearjerker “Here Lies My

Love,” another tune written for the

stage. Powell summed up the poignancy of

the evening (and of aging) in his vocal

rendering of “For All We Know.”

Born in New Orleans, March 1, 1930,

Powell was admired equally as a

performer and an educator. He attended

Alabama State Teachers College before

going on the road with the King Kolax

band. He also worked with Ernie Fields

and Lionel Hampton until joining the

Basie band in 1951. He remained with

Basie for 12 years, winning DownBeat

magazine’s critics’ poll in 1956.

After leaving Basie, Powell was became a

popular studio musician, making many

small group dates and big band sessions.

He played in the Broadway pit orchestra

for “Funny Girl” in 1964. As an

occasional actor, he had a small role in

“A Man Called Adam” (1966), starring

Sammy Davis Jr., and played in the

onscreen Basie band in “Blazing Saddles”

in 1974. Powell’s adventurous sound

bridged the gap between swing, bop and

world music, later working with Abdullah

Ibrahim, Randy Weston and John Carter.

As an educator, Powell helped to direct

the Jazzmobile program, which brought

jazz to disadvantaged areas of New York

City. He also taught at the New School

University until the close of his

career. He was named a National

Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master.

Powell died at Roosevelt Hospital in New

York City, apparently of a heart attack,

while recovering from successful spinal

surgery. Three times divorced, Powell is

survived by his daughter, Demetra, and

grandchildren, Faith and Kyle, and by

his sister, Elizabeth.

A traditional jazz service was held July

12 at St. Peter’s Church in New York

City. Among those who performed were

Randy Weston and African Rhythms and

Nextep, a group featuring saxophonist

Frank Wess (and the group with whom Powell

recorded a 2008 release). One of

Powell’s nieces performed a classical

piece on violin. Weston also gave a

moving nine-minute eulogy in honor of

his longtime friend and bandmate.

“Benny Powell represents the essence of

our music,” Weston said. “Our music is

more than notes and scales. It’s more

than paper and gigs. It’s spirit, and

musicians have been given the gift of

spirit.”

top |

|

NJO, Lied and Brownville concert

series |

|

By Tom Ineck

LINCOLN, Neb.—Jazz and other great

American music are on the bill in coming

months at various area venues. Mark your

calendars and support live music!

![Wayne Bergeron [Courtesy Photo]](media/710Bergeron.jpg) After

a year of financial struggle,

reassessment and retrenchment in which

most of its concerts featured members of

the band the Nebraska Jazz Orchestra is

back with one of its strongest seasons

in years. It all begins Oct. 15 at the

Lied Center for Performing Arts, where

the NJO again will feature famed

trumpeter Wayne Bergeron, who was

in less than stellar condition when he

appeared with the band last October.

Having just suffered a lip injury that

curtailed his playing, he had to rely on

able protégé Willie Murillo. Rest

assured, Bergeron fans will hear from

the man himself at the Lied. After

a year of financial struggle,

reassessment and retrenchment in which

most of its concerts featured members of

the band the Nebraska Jazz Orchestra is

back with one of its strongest seasons

in years. It all begins Oct. 15 at the

Lied Center for Performing Arts, where

the NJO again will feature famed

trumpeter Wayne Bergeron, who was

in less than stellar condition when he

appeared with the band last October.

Having just suffered a lip injury that

curtailed his playing, he had to rely on

able protégé Willie Murillo. Rest

assured, Bergeron fans will hear from

the man himself at the Lied.

On Dec. 14, local actress and singer

Melissa Lewis will join the NJO for

its annual Christmas concert at the

Cornhusker Marriott. Well known for her

skills on the theatrical stage, Lewis is

also garnering raves as a vocalist of

formidable technique and crowd-pleasing

showmanship.

![Scott Robinson and contrabass saxophone [Courtesy Photo]](media/710Robinson.jpg) Multi-instrumentalist

Scott Robinson will appear as

guest soloist with the NJO Feb. 18 at

the Marriott. A 1981 graduate of the

Berklee College of Music in Boston, he

joined its staff the next year to become

the youngest faculty member in the

school’s history. He stayed until 1984,

when he moved to New York City, later

working with Buck Clayton, Lionel

Hampton, and Paquito D’Rivera. He has

also written film music and has been

awarded four fellowships by the National

Endowment for the Arts. Among the

unusual reed instruments he plays are

the contrabass saxophone and C-Melody

saxophone. Multi-instrumentalist

Scott Robinson will appear as

guest soloist with the NJO Feb. 18 at

the Marriott. A 1981 graduate of the

Berklee College of Music in Boston, he

joined its staff the next year to become

the youngest faculty member in the

school’s history. He stayed until 1984,

when he moved to New York City, later

working with Buck Clayton, Lionel

Hampton, and Paquito D’Rivera. He has

also written film music and has been

awarded four fellowships by the National

Endowment for the Arts. Among the

unusual reed instruments he plays are

the contrabass saxophone and C-Melody

saxophone.

On April 26 veteran NJO bassist Andy

Hall will be featured in “Ace of

Bass,” a program devoted to the music of

Jaco Pastorius as arranged for big band

by Peter Graves, whose band Pastorius

played with when still quite young.

Graves has produced two all-star CD

collections of his big-band arrangements

of Pastorius tunes, 2003’s “Word of

Mouth Revisited” and 2006’s “The Word is

![Terence Blanchard [Courtesy Photo]](media/710Blanchard.jpg) Out!”

Hall’s aggressive, virtuosic bass style,

which owes much to Pastorius, should be

ideal for these challenging tunes. Out!”

Hall’s aggressive, virtuosic bass style,

which owes much to Pastorius, should be

ideal for these challenging tunes.

In addition to the NJO appearance Oct.

15, the upcoming Lied Center season

includes several other notable jazz

concerts. Branford Marsalis and

Terence Blanchard will team up

for a Feb. 25 performance that brings

together two New Orleans natives who are

among the leaders in mainstream jazz of

the 21st century.

A concert Dec. 11 will feature the

Boston Brass and Brass All-Stars Big

Band in a holiday tribute, with 14

horns and a rhythm section performing

the famous Stan Kenton Christmas carols

and other holiday hits. The ensemble’s

recording of the Kenton pieces was

released in 2005.

![Trombonist Bill Hughes leads the Count Basie Orchestra [Courtesy Photo]](media/710Basie1.jpg) More

than 26 years after the death of its

founder, the legendary Count Basie

Orchestra continues to thrill

audiences with its unique style of

blues-based Kansas City swing. The band

will appear March 18 at the Lied. Now

directed by trombonist Bill Hughes, the

band has never stopped touring and

recording. Its most recent release is

“Basie Is Back,” recorded live in Japan

in 2005. More

than 26 years after the death of its

founder, the legendary Count Basie

Orchestra continues to thrill

audiences with its unique style of

blues-based Kansas City swing. The band

will appear March 18 at the Lied. Now

directed by trombonist Bill Hughes, the

band has never stopped touring and

recording. Its most recent release is

“Basie Is Back,” recorded live in Japan

in 2005.

Down the road about 80 miles, the

Brownville Concert Hall continues its 20th

anniversary season with additional

![KT Sullivan and Mark Nadler [Courtesy Photo]](media/710SullivanNadler.jpg) performances

booked in Lincoln and Omaha. The

“Cavalcade of Cabaret” will feature

world-class cabaret singer KT

Sullivan and singer-pianist Mark

Nadler in a series of concerts

beginning Aug. 13 in Brownville and

continuing Aug. 14 at the Omaha

Community Playhouse. A month later, they

return to the area for performances

Sept. 9 at the Rococo Theater in Lincoln

and Sept. 10-12 in Brownville. performances

booked in Lincoln and Omaha. The

“Cavalcade of Cabaret” will feature

world-class cabaret singer KT

Sullivan and singer-pianist Mark

Nadler in a series of concerts

beginning Aug. 13 in Brownville and

continuing Aug. 14 at the Omaha

Community Playhouse. A month later, they

return to the area for performances

Sept. 9 at the Rococo Theater in Lincoln

and Sept. 10-12 in Brownville.

If you want to venture still further

down the road, the Folly Theater in

Kansas City continues another excellent

jazz concert series with performances

Sept. 25 by The Bad Plus, Oct. 14

by the Dave Brubeck Quartet, Dec.

10 by singer Sachal Vasandani,

Jan. 15 by the Earl Klugh Quartet,

April 2 by Joe Lovano Us Five,

and May 7 by Karrin Allyson.

top |

|

Essay

Charles Mingus and the Racial Mountain |

|

The following essay was written for a class in African-American

literature that I took at the University of

Nebraska-Lincoln during the spring 2010 semester. It was a mid-term paper required by course instructor Megan Peabody. Since it

deals with the music and personal struggle of Charles Mingus, I

thought it appropriate for BMF readers. I also liked the idea of

recycling the essay for a broader audience. I have altered the scholarly

formatting and page citations for a more journalistic approach.

By Tom

Ineck

“Our

folk music, having achieved world-wide fame, offers itself to the genius

of the great individual American composer who is to come.”

![Langston Hughes [Courtesy Photo]](media/710Hughes.jpg) When

this prophetic statement by Langston Hughes first appeared in his essay

“The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” in 1926, jazz was still in

its infancy. Its earliest recordings were less than 10 years old, and

its most influential artists—Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Duke

Ellington—were just beginning to build a popular following at dance

clubs and concert halls in Chicago, New York City and abroad. But in the

ethnic idiosyncrasies of the music’s melodies, harmonies, rhythms and

lyrics, Hughes already hears the free expression of his race as it draws

material and inspiration from every aspect of life and transforms it

into art that speaks to everyone. Since Hughes sounded his clarion call

for black artists to draw on their own lives and the history of African

American culture for inspiration, generations of black musicians have

heeded the message. They find ample material in the spirituals of their

religious practices, in the unfettered joy of their roadhouses, even in

the drudgery of their workaday worlds. When

this prophetic statement by Langston Hughes first appeared in his essay

“The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” in 1926, jazz was still in

its infancy. Its earliest recordings were less than 10 years old, and

its most influential artists—Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Duke

Ellington—were just beginning to build a popular following at dance

clubs and concert halls in Chicago, New York City and abroad. But in the

ethnic idiosyncrasies of the music’s melodies, harmonies, rhythms and

lyrics, Hughes already hears the free expression of his race as it draws

material and inspiration from every aspect of life and transforms it

into art that speaks to everyone. Since Hughes sounded his clarion call

for black artists to draw on their own lives and the history of African

American culture for inspiration, generations of black musicians have

heeded the message. They find ample material in the spirituals of their

religious practices, in the unfettered joy of their roadhouses, even in

the drudgery of their workaday worlds.

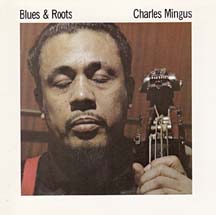

![Charles Mingus [Courtesy Photo]](media/710Mingus.jpg) Composer,

bandleader and bassist Charles Mingus (1922-1979) is one of the most

vivid examples of a black artist who draws on his own experiences in the

context of African American history and culture and creates potent

music. He combines the power of the blues, work songs, and spirituals

with the complex rhythms of African folk drumming and black dance forms.

He occasionally orchestrates his larger ensembles in the manner of

European symphonic music, but always in a style that is distinctly—even

defiantly—his own, an attribute that Hughes would have appreciated. By

looking at just two Mingus recordings—"Blues and Roots" from 1960 and

"The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady" from 1963—we can form a portrait

of the artist and the impulses that stimulated his artistic vision,

impulses rooted in the African American experience of which Hughes

wrote. Original liner notes and re-appraisals by Mingus and others

reveal an artist who struggles with racism and acceptance, emotional

pain and depression, but always strives to create music that is genuine. Composer,

bandleader and bassist Charles Mingus (1922-1979) is one of the most

vivid examples of a black artist who draws on his own experiences in the

context of African American history and culture and creates potent

music. He combines the power of the blues, work songs, and spirituals

with the complex rhythms of African folk drumming and black dance forms.

He occasionally orchestrates his larger ensembles in the manner of

European symphonic music, but always in a style that is distinctly—even

defiantly—his own, an attribute that Hughes would have appreciated. By

looking at just two Mingus recordings—"Blues and Roots" from 1960 and

"The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady" from 1963—we can form a portrait

of the artist and the impulses that stimulated his artistic vision,

impulses rooted in the African American experience of which Hughes

wrote. Original liner notes and re-appraisals by Mingus and others

reveal an artist who struggles with racism and acceptance, emotional

pain and depression, but always strives to create music that is genuine.

A man

sensitive to racial discrimination, as well as the larger issues of

human rights and world peace, Mingus tells jazz critic Nat Hentoff,

“It’s not only a question of color anymore. It’s getting deeper than

that. I mean it’s getting more and more difficult for a man or woman to

just love. People are getting so fragmented, and part of that is fewer

and fewer people are making a real effort anymore to find exactly who

they are.” ("Blues and Roots" liner notes). He epitomizes the black

artist whom Hughes envisions when he writes, “jazz to me is one of the

inherent expressions of Negro life in America; the eternal tom-tom

beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a

white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom

of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed with a smile.” The composer is

brutally honest as he tells Hentoff, “music […] is, or was, a language

of

the

emotions. If someone has been escaping reality, I don’t expect him to

dig my music…. My music is alive and it’s about the living and the dead,

about good and evil. It’s angry, yet it’s real because it knows it’s

angry.” the

emotions. If someone has been escaping reality, I don’t expect him to

dig my music…. My music is alive and it’s about the living and the dead,

about good and evil. It’s angry, yet it’s real because it knows it’s

angry.”

Hughes

singles out “the low-down folks, the so-called common element” as those

most likely to create genuine art from everyday experience, including

religious experience. “Their joy runs, bang! into ecstasy. Their

religion soars to a shout…. These common people are not afraid of

spirituals, as for a long time their more intellectual brethren were,

and jazz is their child.” As Hughes urges, Mingus taps his spiritual

roots for the fiery gospel tune “Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting,” which

the composer describes as “church music. I heard this as a child when I

went to meetings with my mother. The congregation gives their

testimonial before the Lord, they confess their sins and sing and shout

and do a little Holy Rolling.” ("Blues and Roots" liner notes)

Hentoff

helps us understand Mingus’ musical influences, writing in the liner

notes to "Blues and Roots," “Mingus sure knew and felt his roots. He had

played, after all, with the whole range of jazz—from Kid Ory to Charlie

Parker. He knew the entire language—from the inside.” Most blues tunes

are simple constructions of just three predominant chords repeated over

and over, allowing jazz soloists to freely express themselves with

infinite melodic variations within the finite chord structure. Both

Hughes and Mingus understand the potential for black artists to relate a

range of emotions using the blues. In the relations between blacks and

whites, Hughes suggests a wealth of potential themes that “the Negro

artist can give his racial individuality, his heritage of rhythm and

warmth, and his incongruous humor that so often, as in the blues,

becomes ironic laughter mixed with tears.” With “Cryin’ Blues,” “Moanin’,”

and “Tensions,” Mingus thoroughly explore the blues, eventually shouting

in ecstasy (or anguish?) near the end of the final piece.

Despite its

thematic title and dance references, "The Black Saint and the Sinner

Lady" is a large-scale symphonic piece comprised of four “movements”

totaling 40 minutes. It contains no libretto or plot line other than

that vaguely suggested by the provocative subtitles, such as “(Soul

Fusion) Freewoman and Oh, This Freedom’s Slave Cries,” and “Of Love,

Pain and Passioned Revolt, then Farewell, My Beloved, ’til It’s Freedom

Day.” The music seethes with a range of emotions, the horns alternately

weeping and crying out, the complex rhythms colliding or accelerating

wildly, the result sometimes closer to cacophony than harmony. As Mingus

asserts in the liner notes, “This music is only one little wave of

styles and waves of little ideas my mind has

encompassed

through living in a society that calls itself sane.” It is a statement

of personal integrity and bold defiance in the face of the dominant

white culture, and it recalls Hughes’ ultimatum that, “If white people

are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we

are beautiful. And ugly too.” encompassed

through living in a society that calls itself sane.” It is a statement

of personal integrity and bold defiance in the face of the dominant

white culture, and it recalls Hughes’ ultimatum that, “If white people

are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we

are beautiful. And ugly too.”

Aware that

he has difficulty articulating—in words—the conflicted impulses behind

the music of "The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady," the composer asks

psychologist and friend Dr. Edmund Pollock to shed light on the artist

and this monumental work. Pollock quickly gets to the heart of the

matter, writing of Mingus, "His music is a call for acceptance, respect,

love, understanding, fellowship, freedom—a plea to change the evil in

man and to end hatred. The titles of this composition suggest the plight

of the black man and a plea to the white man to be aware. He seems to

state that the black man is not alone but all mankind must unite in

revolution against any society that restricts freedom and human rights."

A note of hope arises near the end of the piece, and Pollock offers a

cautious prediction about the composer, his music and his struggle to

function in a dysfunctional world, writing, “It must be emphasized that

Mr. Mingus is not yet complete, He is still in a process of change and

personal development. Hopefully the integration in society will keep

pace with his.”

As Pollock

foresaw, Mingus continued to develop as an artist, releasing a dozen

more recordings before his death at age 56 in January 1979, from

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease). His music still

resonates more than 30 years later. Summarizing "Blues and Roots,"

Hentoff writes, “As this album powerfully affirms, Mingus’ music will

remain alive so long as there is life in the world.” In his immortal

recordings and their impact on countless composers, musicians, writers

and other artists, Mingus seems to echo the Hughes credo: “We build our

temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the

mountain, free within ourselves.”

top |

|

Tomfoolery

Natural

disaster, death, youth, and music |

|

By Tom Ineck

LINCOLN, Neb.—Even in the best of times,

travel is a process of self-discovery.

In the midst of cataclysmic natural

disaster and the long-distance death of

a loved one, the lessons you learn can

assume epic proportions. For me, those

lessons usually involve the healing

power of music and the importance of

friends

![New Orleans resident and cousin Jerry Siefken with Tom Ineck [Photo by Mary Jane Gruba]](media/710NOJFJerryTom.jpg) and

family. Of course, you don’t have to

leave your home town to appreciate the

resilience of life, love and friendship.

Three recent events brought these

thoughts home. and

family. Of course, you don’t have to

leave your home town to appreciate the

resilience of life, love and friendship.

Three recent events brought these

thoughts home.

My wife and I arrived in New Orleans on

April 28 for Jazz Fest music, food and

fun. But just eight days earlier, the

Deepwater Horizon oil rig had exploded,

killing 11 people and causing the worst

oil spill in U.S. history. Already,

experts were predicting the immense

scale of ecological damage and economic

misery that would follow. With typical

fatalism, longtime New Orleans

residents, like my cousin Jerry Siefken,

took it in stride, mixing a healthy

distrust of authority with the sense

that life would go on. It was a lesson

they had learned many times over, most

recently in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina

nearly wiped the city off the map. And

what would help them get through the

dark days ahead? Music!

![Tom Ineck, Joe Phillips, Nikki Farrer and Kelly McKeen, friends for 40 years [Photo by Michelle Jensen]](media/710HealdsburgGang.jpg) In

early June I returned to Northern

California and the Healdsburg Jazz

Festival, where I had spent a week last

summer with friends who live near

Occidental. While we were in the middle

of a particularly profound performance

by Charlie Haden, Geri Allen and Ravi

Coltrane at the Raven Theater in

Healdsburg, I learned that my

brother-in-law Bob Doulas had died back

in Lincoln. I knew he was near death

when I left on the trip and had been in

touch with my sister for updates on his

condition. When the call came, my cell

phone began to vibrate. Oddly, it felt

like the passing of a spirit. What

helped me cope with that sad

realization? Friends and music! In

early June I returned to Northern

California and the Healdsburg Jazz

Festival, where I had spent a week last

summer with friends who live near

Occidental. While we were in the middle

of a particularly profound performance

by Charlie Haden, Geri Allen and Ravi

Coltrane at the Raven Theater in

Healdsburg, I learned that my

brother-in-law Bob Doulas had died back

in Lincoln. I knew he was near death

when I left on the trip and had been in

touch with my sister for updates on his

condition. When the call came, my cell

phone began to vibrate. Oddly, it felt

like the passing of a spirit. What

helped me cope with that sad

realization? Friends and music!

For the second consecutive year, the

Jazz in June concert series offered five

Tuesday evening concerts. They ran the

gamut from the straight-ahead jazz of

trumpeter Darryl White and his excellent

combo to the Latin lilt of Otro Mundo to

the sensuous vocals of Angela Hagenbach

to the New Orleans swagger of Jeff

![Brief chat with Bill Frisell (right) after his performanc at Healdsburg Jazz Festival [Photo by Kelly McKeen]](media/710HealdsburgFrisellMe.jpg) Newell’s

New-Trad Octet to the progressive guitar

work of Jerry Hahn. The last two were

especially delightful, allowing us to

bring friends of the Berman Music

Foundation back to Lincoln after an

absence of several years. Newell had not

performed here since 2006 and Hahn was

last here in 2005. Newell’s

New-Trad Octet to the progressive guitar

work of Jerry Hahn. The last two were

especially delightful, allowing us to

bring friends of the Berman Music

Foundation back to Lincoln after an

absence of several years. Newell had not

performed here since 2006 and Hahn was

last here in 2005.

Best of all, Newell and Hahn were able

to join us at BMF offices for

post-concert receptions. The entire

New-Trad ensemble partied with us until

midnight, and then ventured to the Zoo

Bar to sit in with the local Jazzocracy

band until closing. Hahn arrived alone,

but stayed for a couple of hours,

chatting about everything from the

foundation’s 15-year history to his own

50-year career as a performer, recording

artist and music educator.

Among other things, we revisited the

meteoric rise and fall of The Jerry Hahn

Brotherhood, the legendary quartet that

combined elements of jazz, rock and

![Jerry Hahn and Tom Ineck with an autographed copy of the rare Jerry Hahn Brotherhood LP. [Photo by Grace Sankey-Berman]](media/710Receptions10.jpg) r&b.

Hahn, bassist Mel Graves, and drummer

George Marsh had been gigging as a jazz

trio in the San Francisco Bay area in

the late 1960s when they were introduced

to the brilliant organist and vocalist

Mike Finnigan. Armed with a set of great

tunes by Lane Tietgen, Ornette Coleman’s

“Ramblin’” and a couple of originals by

Hahn, they recorded a single self-titled

recording on Columbia and toured behind

it until the record company promotion

fizzled and the money ran out. Left

behind are the memories of those lucky

few of us who attended a Brotherhood

concert. My opportunity came in July

1970 at the band’s Denver stop, a

performance also attended by a

19-year-old Bill Frisell, who I just saw

in June out in California. Serendipity. r&b.

Hahn, bassist Mel Graves, and drummer

George Marsh had been gigging as a jazz

trio in the San Francisco Bay area in

the late 1960s when they were introduced

to the brilliant organist and vocalist

Mike Finnigan. Armed with a set of great

tunes by Lane Tietgen, Ornette Coleman’s

“Ramblin’” and a couple of originals by

Hahn, they recorded a single self-titled

recording on Columbia and toured behind

it until the record company promotion

fizzled and the money ran out. Left

behind are the memories of those lucky

few of us who attended a Brotherhood

concert. My opportunity came in July

1970 at the band’s Denver stop, a

performance also attended by a

19-year-old Bill Frisell, who I just saw

in June out in California. Serendipity.

It seemed that talking about those

events of 40 years ago allowed both Hahn

and me to revisit our youth and an

exciting period in American pop culture.

What was the common bond? Music, of

course!

top |

|

|

|

Editor’s Note:

At your request, we will mail a printed version

of the newsletter. The online newsletter also is available at this

website in PDF format for printing. Just click here: Newsletter

|

|